In the last of our weekly readings, my daughter’s 4th grade class read Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Pit And The Pendulum” (a two minute read) and today I led the kids in a discussion of the story. Here are my notes.

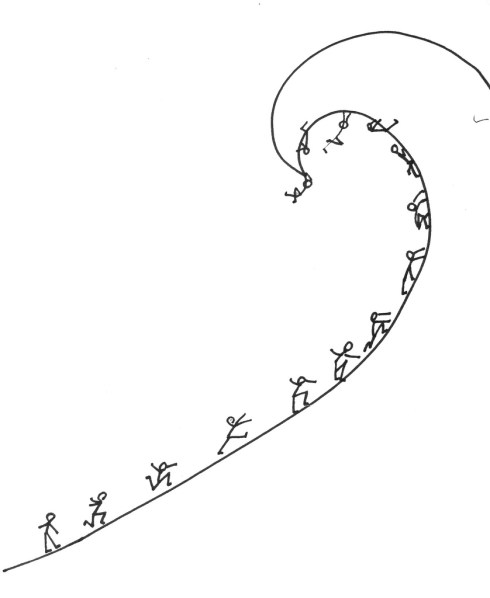

The story reads like a scholarly thesis on the art and strategy of torture. My fourth graders had no trouble picking out the themes of commitment, credibility, resistance, and escalation as if they themselves were seasoned experts on the age-old institution. We went around the table associating passages in the story to everyday scenes on the playground and in the lunch line. Many of the children especially identified with this account of the delicate balance between hope and despair in the victim:

And then there stole into my fancy, like a rich musical note, the thought of what sweet rest there must be in the grave. The thought came gently and stealthily, and it seemed long before it attained full appreciation; but just as my spirit came at length properly to feel and entertain it, the figures of the judges vanished, as if magically, from before me; the tall candles sank into nothingness; their flames went out utterly; the blackness of darkness supervened; all sensations appeared swallowed up in a mad rushing descent as of the soul into Hades.

We had a lengthy discussion of how the victim was made to wish for death and one especially precocious youngster observed that the longing for death cultivates in the detainee what is known as the Stockholm Syndrome in which the victim begins to feel a sense of common purpose with his captors.

By long suffering my nerves had been unstrung, until I trembled at the sound of my own voice, and had become in every respect a fitting subject for the species of torture which awaited me.

Here Poe gives a nod to the eternal debate about the psychology of torture. Does psychological stress of torture bring the victim to a state in which he abandons all rationality? There in the hush of the elementary school library, the children were insistent that Poe was right to suggest instead that torture, judiciously applied, only heightens the victim’s strategic awareness.

In light of that observation it came as no surprise to the sharpest among my students that the instrument to be used would leverage to the fullest the interrogators’ strategic advantage in this contest of wills.

It might have been half an hour, perhaps even an hour, (for in cast my I could take but imperfect note of time) before I again cast my eyes upward. What I then saw confounded and amazed me. The sweep of the pendulum had increased in extent by nearly a yard. As a natural consequence, its velocity was also much greater. But what mainly disturbed me was the idea that had perceptibly descended. I now observed — with what horror it is needless to say — that its nether extremity was formed of a crescent of glittering steel, about a foot in length from horn to horn; the horns upward, and the under edge evidently as keen as that of a razor. Like a razor also, it seemed massy and heavy, tapering from the edge into a solid and broad structure above. It was appended to a weighty rod of brass, and the whole hissed as it swung through the air.

Still we were, every one of us, in awe of Poe’s ingenious device. The pendulum, serving both as a symbol of the deterministic and inexorable march of time, and a literal instrument of torture inheriting that same aura of inevitability.

I asked the youngest of my students, a gentle and charming, if somewhat reserved little girl to take her reader out of her Hello Kitty book bag and read aloud this entry, which I had highlighted as one whose vibrant color and imagery was sure to endear the students at such an early age to the rich joys of literature.

What boots it to tell of the long, long hours of horror more than mortal, during which I counted the rushing vibrations of the steel! Inch by inch — line by line — with a descent only appreciable at intervals that seemed ages — down and still down it came! Days passed — it might have been that many days passed — ere it swept so closely over me as to fan me with its acrid breath. The odor of the sharp steel forced itself into my nostrils. I prayed — I wearied heaven with my prayer for its more speedy descent.

This was the moment of my greatest pride in our weekly literary expeditions as I could tell that the child so was overcome with the joy and power of Poe’s insights into the art of interrogation, that she was nearly weeping at the end.

The story concludes with Poe’s most hopeful verdict on the limits of torture as a mechanism. Our victim persevered, resisted to the very end, and his steadfastness was rewarded with escape and rescue. Likewise, the little boys and girls went back to their classroom and I detected that they were moving unusually slowly. I surmised, I must say with a little pride, that they were still deep in thought about the valuable lesson we had explored together. Indeed many of them confided in me that they were eager to tell their parents about me and the story I picked for them and everything they learned today.