You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘statistics’ tag.

If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?

This old philosophical conundrum can be mapped into the dilemma facing the aging academic:

If I publish a paper and nobody reads it, teaches it or cites it, can it ever be a truly great paper?

As with all questions with no Platonic certitude, economists say: Let the market speak and tell us the answer.

Glenn Ellison has studied a more serious version of my question in his paper “How Does the Market Use Citation Data? The Hirsch Index in Economics.” The Hirsch index for an author is the highest number h such that the author has h papers with at least h citations. So, an index of 5 means you have five papers with at least five citations and that you do not have six papers with at least six citations etc.

Glenn points out that the Hirsch index doesn’t do a great job at ranking economists. Nobel prize winner Roger Myerson’s Hirsch index is a mere 32. But he has a few papers with over a thousand citations. Seminal papers in economics tend to get a huge number of citations but most only get a few. So, the plain vanilla Hirsch index needs to be re-evaluated.

Glenn turns to the market to guide his measure. He studies an index of the form h is the highest number such that the author has at least h papers with at least a times h to the power b citations. The plain vanilla Hirsch index sets a=b=1. Glenn estimates a and b in various ways. In one method, he looks at the NRC department rankings and finds the variables a and b that best predict the NRC rank of a (young) economist’s department. To cut a long story short, a=5 and b=2 come out as the best predictors. With this estimation in hand, we can perform various comparisons – Which fields are highly cited? Which economists are highly cited? Etc..

Here are some tasty morsels of information. International finance, trade and behavioral economics are highly cited fields (Table 6). Micro theory and cross-sectional econometrics are the worst and IO does not do too well either. These facts mean Yale and NU, which are strong in these three areas, are under-cited economics departments. But basically one gets the picture that an economists citations are closely connected to the rank of the university where s/he is employed.

Ranking young economists, it is pretty obvious who is going to come out on top: Daron Acemoglu with an index of 7.84 (Table 7). This means Daron has 7.84 papers with roughly 300 citations. Ed Glaeser and Chad Jones are close behind. Once you adjust by field, more theorists start to rank highly: Glenn, Ilya Segal, Stephen Morris and Susan Athey pop up. Also, my friend Aviv Nevo gets a shout out as an underplaced guy.

A few comments:

Most of these people are tenured well before their citations go crazy. Expert opinion not data-mining leads to their tenure. This tells you how well expert opinion predicts citations. Also, to the extent that citations take time, expert opinion will always play a role in tenure decisions. There is a difference between external opinion and internal opinion. The same few people always get asked to write letters and they will do a good job. But internal opinions may be more noisy and depend on the quality of the department. Then, Glenn’s field-adjusted citation measure gives you some idea of a candidate’s quality and might be a valuable input into the tenure decision.

Finally, there are citations and citations. A paper getting regular cites in top journals is better than a paper getting cites in lower tier journals. This can be dealt with by improving the citation index.

At another extreme, some papers may be journalistic, not academic, and then their citations mean less. For example, Malcom Gladwell gets high citations for the Tipping Point but he did not do any of the original scientific research on which his book is based. Of course he writes wonderfully and comes up with amazing examples and he is clearly an intellectual. I bet Harvard would love to have him an as an adjunct professor but they will not give him a tenured professorship.

Despite these caveats, the generalized Hirsch index is an interesting input for academic decision-making.

They say you can’t compare the greats from yesteryear with the stars of today. But when it comes to Nobel laureates, to some extent you can.

The Nobel committee is just like a kid with a bag of candy. Every day (year) he has to decide which piece of candy to eat (to whom to give the prize) and each day some new candy might be added to his bag (new candidates come on the scene.) The twist is that each piece of candy has a random expiration date (economists randomly perish) so sometimes it is optimal to defer eating his favorite piece of candy in order to enjoy another which otherwise might go to waste.

The empirical question we are then left with is to uncover the Nobel committee’s underlying ranking of economists based on the awards actually given over time. It’s not so simple, but there are some clear inferences we can make. (Here’s a list of Laureates up to 2006, with their ages.)

To see that it is not so simple, note that just because X got the prize and Y didn’t doesn’t mean that X is better than Y. It could have been that the committee planned eventually to give the prize to Y but Y died earlier than expected (or Y is still alive and the time has not yet arrrived.)

When would the committee award the prize to X before Y despite ranking Y ahead of X? A necessary condition is that Y is older than X and is therefore going to expire sooner. (I am assuming here that age is a sufficient statistic for mortality risk.) That gives us our one clear inference:

If X received the prize before Y and X was born later than Y then X is revealed to be better than Y.

(The specific wording is to emphasize that it is calendar age that matters, not age at the time of receiving the prize. Also if Y never received the prize at all that counts too.)

Looking at the data, we can then infer some rankings.

One of the first economists to win the prize, Ragnar Frisch (who??) is not revealed preferred to anybody. By contrast, Paul Samuelson, who won the very next year is revealed preferred to kuznets, hicks, leontif, von hayk, myrdal, kantorovich, koopmans, friedman, meade, ohlin, lewis, schulz, stigler, stone, allais, haavelmo, coase and vickrey.

Outdoing Samuelson is Ken Arrow, who is revealed preferred to everyone Samuelson is plus simon, klein, tobin, debreu, buchanan, north, harsanyi, schelling and hurwicz (! hurwicz won the prize 37 years later!), but minus kuznets (a total of 25!)

Also very impressive is Robert Merton who had an incredible streak of being revealed preferred to everyone winning the prize from 1998 to 2006, ended only by Maskin and Myerson (but see below.)

On the flipside, there’s Tom Schelling who is revealed to be worse than 28 other Laureates. Leo Hurwicz is revealed to be worse than all of those plus Phelps. Hurwicz is not revealed preferred to anybody, a distinction he shares with Vickrey, Havelmo, Schultz (who??), Myrdal (?), Kuznets and Frisch.

Paul Krugman is batting 1,000 having been revealed preferred to all (two) candidates coming after him: Williamson and Ostrom.

Similar exercises could be carried out with any prize that has a “lifetime achievement” flavor (for example Sophia Loren is revealed preferred to Sidney Poitier, natch.)

There’s a real research program here which should send decision theorists racing to their whiteboards. We deduced one revealed preference implication. Question: is that all we can deduce or are there other implied relations? This is actually a family of questions that depend on how strong assumptions we want to make about the expiration dates in the candy bag. At one extreme we could ask “is any ranking consistent with the boldface rule above rationalizable by some expiration dates known to the child but not to us?” My conjecture is yes, i.e. that the boldface rule exhausts all we can infer.

At the other end, we might assume that the committee knows only the age of the candidates and assumes that everyone of a given age has the average mortality rate for that age (in the United States or Europe.) This potentially makes it harder to rationalize arbitrary choices and could lead to more inferences. This appears to be a tricky question (the infinite horizon introduces some subtleties. Surely though Ken Arrow has already solved it but is too modest to publish it.)

Of course, the committee might have figured out that we are making inferences like this and then would leverage those to send stronger signals. For example, giving the prize to Krugman at age 56 becomes a very strong signal. This would add some noise.

Finally, the kid-with-a-candy-bag analogy breaks down when we notice that the committee forms bundles. Individual rankings can still be inferred but more considerations come into play. Maskin and Myerson got the prize very young, but Hurwicz, with whom they shared the prize, was very close to expiration. We can say that the oldest in a bundle is revealed preferred to anyone older who receives a prize later. Plus we can infer rankings of fields by looking at the timing of prizes awarded to researchers in similar areas. For example, time-series econometrics (2003) is revealed preferred to the theory of organizations (2009.)

The Bottom Line: There is clear advice here for those hoping to win the prize this year, and those who actually do. If you do win the prize, for your acceptance speech you should start by doing pushups to prove how virile you are. This signals to the world that you were not given the award because of an impending expiration date but that in fact there was still plenty of time left but the committee still saw fit to act now. And if you fear you will never win the prize, the sooner you expire the more willing will the public be to believe that you would have won if only you had stuck around.

Cell phone use increases the risk of traffic accidents right? But how do we prove that? By showing that a large fraction of accidents involve people talking on cell phones? Not enough. A huge fraction of accidents involve people wearing shoes too.

I thought about this for a while and short of a careful randomized experiment it seems hard to get a handle on this using field data. I poked around a bit and I didn’t find much that looked very convincing. To give you an example of the standards of research on this topic, one study I found actually contains the following line:

Results Driver’s use of a mobile phone up to 10 minutes before a crash was associated with a fourfold increased likelihood of crashing (odds ratio 4.1, 95% confidence interval 2.2 to 7.7, P < 0.001).

(Think about that for a second.)

Here’s something we could try. Compare the time trend of accident rates for the overall population of drivers with the same trend restricted to deaf drivers. We would want a time period that begins before the widespread use of mobile phones and continues until today. Presumably the deaf do not talk on cell phones. So if cell phone use contributed to an increase in traffic risk we would see that in the general population but not among the deaf.

On the other hand, the deaf can use text messaging. Since there was a period of time when cell phones were in widespread use but text messaging was not, then this gives us an additional test. If text messaging causes accidents, then this is a bump we should see in both samples.

Anyone know if the data are available? I am serious.

This article from Not Exactly Rocket Science discusses an experiment studying “competition” between the left and right sides of the brain. Subjects in the experiment had to pick up an object placed at different points on a table and what was observed was which hand they used depending on where the object was. The article makes this observation in passing.

they always used the nearest hand to pick up targets at the far edges of the table, but they used either hand for those near the middle. Their reaction times were slower when they had to choose which hand to use, and particularly if the target was near the centre of the table.

This much is expected, but it supports the idea that the brain is choosing between possible movements associated with each hand. At the centre of the table, when the choice is least clear, it takes longer to come down on one hand or the other.

I stopped there. Because while this sounds intuitive, there is another intuition that points squarely in the opposite direction. When the object is in the center of the table, that’s when it matters least which hand you use, so there is no reason to spend extra time thinking about it. Right? So…when you have competing intuitions you need a model.

You have to take an action, say “left” or “right” and your payoff depends on the state of the world, some number between -1 and 1. You prefer “right” when the state is positive and “left” when the state is negative and the farther away from zero is the state, the stronger is that preference. When the state is exactly zero you are indifferent.

You don’t know the state with perfect precision. Instead, you initially receive a noisy signal about the state and you have to decide whether to take action right away (and which action) or wait and get a more accurate signal. It’s costly to wait. For what values of the initial signal do you wait? Note that in this model, both of the competing intuitions are present. If your initial signal is close to zero, it is likely that the true state is close to zero so your loss from choosing the wrong action is small. Thus the gain from waiting for better information is small. On the other hand, if your initial signal is far from zero, then the new information is unlikely to affect which action you take so again the gain from waiting is small.

But now we can compute the relative gain. And the in-passing intuition quoted above is the winner.

Consider two possible values of the initial signal, both positive but one close to zero and one close to +1. In either case if you don’t wait you will take action “right.” Now consider the gain from waiting. Take any state x and let’s consider the scenario where waiting would lead you to believe that the state is x. If x is positive then you would still choose “right” and waiting would not gain anything. So fix any negative x and ask what would the gain be if waiting led you to believe that the state is x. The key observation is that for any fixed x, this gain would be the same regardless of which of the initial signals you had.

So the comparison then just boils down to comparing how likely it is to switch to x from the two different initial signals. And this comparison depends on how far to the left x is. Signals very close to -1 are much easier to reach from an initial signal close to zero than from an initial signal close to 1. And these are the signals where the gain is large. On the other hand, for x’s just to the left of zero (where the gain is small), the relative likelihood of reaching x from the two initial signals is closer to 50-50.

Formally, unless the distribution generating these signals is very strange, the distribution of payoff gains after an initial signal close to zero first-order stochastically dominates the distribution of payoff gains when you start close to 1. So you are always more inclined to wait when your initial signal is close to zero.

For 15 years, the British bookmaker William Hill allowed bettors to wager on their own weight loss, often taking out full-page newspaper ads to publicize the bet. This was a clear opportunity for those looking to lose weight to make a commitment, with real teeth. Here is a paper by Nicholas Burger and John Lynham which analyzes the data.

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2, which shows that 80% of bettors lose their bets. Odds for the bets range from 5:1 to 50:1 and potential payoffs average $2332.9 The average daily weight loss that a bettor must achieve to win their bet is 0.39 lbs. In terms of reducing caloric intake to lose weight, this is equivalent to reducing daily consumption by two Starbucks hot chocolates. The first insight we draw from this market is that although bettors are aware of their need for commitment mechanisms, those in our sample are not particularly skilled at selecting the right mechanisms.10 Bettors go to great lengths to construct elaborate constraints on their behaviour, which are usually unsuccessful.

Women do much worse than men. Bets in which the winnings were committed to charity outperformed the average. Bets with a longer duration (Lose 2x pounds in 2T days rather than x pounds in T days) have longer odds, suggesting that the market understands time inconsistency.

Beanie barrage: barker.

Is the United States the world’s dominant exporter of culture? If this were true of any area you would think that area would be pop music. But it appears not to be the case.

In this paper we provide stylized facts about the global music consumption and trade since 1960, using a unique data on popular music charts from 22 countries, corresponding to over 98% of the global music market. We find that trade volumes are higher between countries that are geographically closer and between those that share a language. Contrary to growing fears about large- country dominance, trade shares are roughly proportional to country GDP shares; and relative to GDP, the US music share is substantially below the shares of other smaller countries. We find a substantial bias toward domestic music which has, perhaps surprisingly, increased sharply in the past decade. We find no evidence that new communications channels – such as the growth of country-specific MTV channels and Internet penetration – reduce the consumption of domestic music. National policies aimed at preventing the death of local culture, such as radio airplay quotas, may explain part of the increasing consumption of local music.

Here is the paper by Ferreira and Waldfogel. And before you click on this link, guess which country is the largest exporter as a fraction of GDP.

The data on first vs. second serve win frequency cannot be taken at face value because of selection problems that bias against second serves. The general idea is that first serves always happen but second serves happen only when first serves miss. The fact that the first serve missed is information that at this moment serving is harder than usual. In practice this can be true for a number of reasons: windy conditions, it is late in the match, or the server is just having a bad streak. In light of this, we can’t conclude from the raw data that professional tennis players are using sub-optimal strategy on second serves.

To get a better comparison we need an identification strategy: some random condition that determines whether the next serve will be a first or second serve. We would restrict our data set to those random selections. Sounds hopeless?

When a first serve hits the net and goes in it is a “let” and the next serve is again a first serve. But if it goes out then it is a fault. The impact with the net introduces the desired randomness, especially when the ball hits the tape and bounces up. Conditional on hitting the tape, whether it lands in or out can be considered statistically independent of the server’s current mental state, the wind conditions, and the stage of the game. These are the ingredients for a “natural experiment.”

In golf:

How big a deal is luck on the golf course? On average, tournament winners are the beneficiaries of 9.6 strokes of good luck. Tiger Woods’ superior putting, you’ll recall, gives him a three-stroke advantage per tournament. Good luck is potentially three times more important. When Connolly and Rendleman looked at the tournament results, they found that (with extremely few exceptions) the top 20 finishers benefitted from some degree of luck. They played better than predicted. So, in order for a golfer to win, he has to both play well and get lucky.

I don’t understand the statistics enough to evaluate this paper. Apparently they call “luck” the residual in some estimate of “skill.” What I don’t understand is how such luck can be distinguished from unexpectedly good performance. If a schlub wins a big tournament and then returns to being a schlub, is that automatically luck?

I liked this post from Dan Reeves.

Remember, if it’s in the news don’t worry about it. The very definition of news is “something that almost never happens.” When something is so common that it’s no longer news — car crashes, domestic violence — that’s when you should worry about it.

The truth of that[1] hit home recently when I saw a news feature on the abduction of a four-year-old girl from her front yard in Missouri. Candlelight vigils, nation-wide amber alert, police blockades where every single car was stopped and questioned, FBI agents swarming the house. I think the expected reaction from parents is “oh my god, I need to be so vigilant, even in my own front yard!” My reaction was the opposite: Wow, this sort of thing really does essentially never happen. Let the kids run free!

While I generally have similar reactions, it is easy to take this too far. The weather is the prime counter-example. Valuable minutes of every nightly newscast in Southern California are devoted to repeating the same weather-mantra “Late Night and Early Morning Low Clouds and Fog” which indeed happens every single day.

Also, your interpretation of news depends on your implicit model of competition between news sources. A perfectly plausible model would be consistent with abductions happening every day but being reported only once in a while because we have a taste for variety in our stories of tragedy.

Cable T.V. is boring, the sky is dark and it’s snowing. What can you do to entertain yourself? One answer:

When Nancy Bonnell, 31, thinks of her baby girl due next month, she recalls the December snow that she and her husband, Brian, endured: “We lived in the apartment and had nothing to do.”So they cooked in their Derwood home, they grew restless and then they — well, you know.

The couple had been trying to have a baby and originally thought it might happen during a post-Christmas vacation to the Cook Islands in the South Pacific. They could nickname her “Cookie Girl,” they thought.

Then Bonnell learned during the second week of January that she was expecting. She deduced that she had conceived sometime during the snowstorm. Time for a new nickname.

“It was more like ‘Snow Angel,’ ” she said.

Yet that theory was quashed in a 1970 paper by Richard Udry, a demographer at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He found no statistically significant upswing in births associated with the blackout. “It is evidently pleasing to many people,” he concluded, “to fantasize that when people are trapped by some immobilizing event which deprives them of their usual activities, most will turn to copulation.”

Despite what you have read, theory holds up just fine.

The relationship between economic theory and experimental evidence is controversial. One could easily get the impression from reading the experimental literature that economic theory has little or no significance for explaining experimental results. The point of this essay is that this is a tremendously misleading impression. Economic theory makes strong predictions about many situations, and is generally quite accurate in predicting behavior in the laboratory. Most familiar situations where the theory is thought to fail, the failure is to properly apply the theory, and not in the theory failing to explain the evidence.

Which is not to say theory doesn’t have its problems.

That said, economic theory still needs to be strengthened to deal with experimental data: the problem is that in too many applications the theory is correct only in the sense that it has little to say about what will happen. Rather than speaking of whether the theory is correct or incorrect, the relevant question turns out to be whether it is useful or not useful. In many instances it is not useful. It may not be able to predict precisely how players will play in unfamiliar situations.4 It buries too much in individual preferences without attempting to understand how individual preferences are related to particular environments. This latter failing is especially true when it comes to preferences involving risk and time, and in preferences involving interpersonal comparisons – altruism, spite and fairness.

Are prejudices magnified depending on the language being spoken? An experiment based on a standard Implicit Association Test suggests yes.

In an Implicit Association Test pairs of words appear in sequence on a screen. Subjects are asked to classify the relationship between the words and then the time taken to determine the association is recorded. In this experiment the word pairs consisted of one name, either Jewish or Arab, and one adjective, either complimentary or negative. The task was to identify these categories, i.e. (Jewish, good); (Jewish, bad); (Arab, good); (Arab, bad).

The subjects were Israeli Arabs who were fluent in both Hebrew and Arabic.

For this study, the bilingual Arab Israelis took the implicit association test in both languages Hebrew and Arabic to see if the language they were using affected their biases about the names. The Arab Israeli volunteers found it easier to associate Arab names with “good” trait words and Jewish names with “bad” trait words than Arab names with “bad” trait words and Jewish names with “good” trait words. But this effect was much stronger when the test was given in Arabic; in the Hebrew session, they showed less of a positive bias toward Arab names over Jewish names. “The language we speak can change the way we think about other people,” says Ward. The results are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

Nice. But this leaves open the possibility that, since Hebrew is the second language, all response times in the Hebrew treatment were increased simply making it harder to see the bias. I would still prefer a design like this one.

Balaclava bluster: Johnson.

You firmly believe that the sun will rise every morning. Then one day you awake and the sun does not rise. What are you to believe now? You have basically two alternatives. One is to go on believing that the sun will rise every morning by rationalizing today’s exception. There could have been a total eclipse this morning. Perhaps you are dreaming. The other choice is to conclude that you were wrong and the sun does not rise every morning.

The “rational” (i.e. Bayesian) reaction is to weigh your prior belief in the alternatives. Yes, to believe that you are dreaming despite many pinches, or to believe that a solar eclipse lasted all day would be to believe something near to absurdity, but given your almost-certainty that the sun would always rise we are already squarely in the exceptional territory of events with very low subjective probability. What matters is the relative proportion of that low total probability made up of the competing hypotheses: some crazy exception happened, or the sun in fact doesn’t always rise. It would be perfectly understandable, indeed rational if you find the first much more likely than the second. That is, even in the face of this contradictory evidence you hold firm to your belief that the sun rises and infer that something else truly unexpected happened.

Cognitive dissonance is a family of theories in psychology explaining how we grapple with contradictory thoughts. It has many branches, but a prominent one and perhaps the earliest, suggests that we irrationally discard information that is in conflict with our preconceived ideas. It began with a study by Leon Festinger. He was observing a cult who believed that the Earth was going to be destroyed on a certain date. When that date passed and the Earth was not destroyed, some members of the cult interpreted this as proof they were right because it was their faith that saved humanity. This was the leading example of cognitive dissonance.

My preamble about Bayesian inference shows that when we see people who are rigid in their beliefs and we conclude that they are irrationally ignoring information, it is in fact we who are jumping to a conclusion. All we can really say is that we disagree with their prior beliefs and in particular the strength of those beliefs. Somehow though it is much less satisfying to just disagree with someone than to say that they are acting irrationally in the face of clear evidence.

Now, watch this video, especially the part that starts at the 3:00 mark. When this guy experiences his moment of cognitive dissonance, what is the rational resolution?

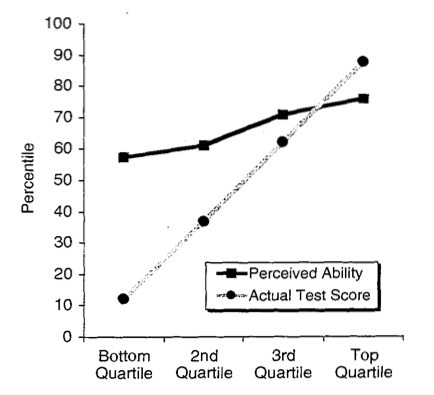

You have probably heard about the science that shows how incompetent people are overconfident. Here is a nice article which cuts through some of the hype and then presents a variety of ways to debunk the finding as a statistical illusion. (Which comes as a relief to me, but perhaps a little late.) Let me give you an even easier way, one that is related to the “regression toward the mean” idea given in the article. First, here is the finding summarized in a graph.

Suppose you have competent and incompetent people in equal proportions. They will take a test which will give them a score ranging from 0 to 4. The competent people score a 3 on average and they know this. The incompetent people score 1 on average and they know this. Due to idiosyncratic features of the test, the weather, etc. each subject’s actual score is random and it will range from one less to one more than their average.

You ask everyone to predict their outcome. The incompetent people predict a score of 1 and the competent people predict a score of 3. These are the best predictions. Then they take the test. The actual scores range from 0 to 4. Everyone who scored 0 predicted a score of 1, everyone who scored 4 predicted a score of 3, and the average prediction of those who scored 2 is about 2.

Trilby tribute: Marginal Revolution.

It gets harder and harder to avoid learning the outcome of a sporting event before you are able to get home and watch it on your DVR. You have to stop surfing news web sites, stay away from Twitter, and be careful which blogs you read. Even then there is no guarantee. Last year I stopped to get a sandwich on the way home to watch a classic Roddick-Federer Wimbledon final (16-14 in the fifth set!) and some soccer-moms mercilessly tossed off a spoiler as an intermezzo between complaints about their nannys.

No matter how hard you try to avoid them, the really spectacular outcomes are going to find you. The thing is, once you notice that you realize that even the lack of a spoiler is a spoiler. If the news doesn’t get to you, then at the margin that makes it more likely that the outcome was not a surprise.

Right now I am watching Serena Williams vs Yet-Another-Anonymous-Eastern-European and YAAEE is up a break in the first set. But I am still almost certain that Serena Williams will win because if she didn’t I probably would have found out about it already.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. Unless the home team is playing, a big part of the interest in sports is the resolution of uncertainty. We value surprise. Moving my prior further in the direction of certainty has at least one benefit: In the event of an upset I am even more surprised. This has to be taken into account when I decide the optimal amount of effort to spend trying to avoid spoilers. It means that I should spend a little less effort than I would if I was ignoring this compensating effect.

It also tells me something about how to spend that effort. I once had a match spoiled by the Huffington Post. I never expected to see sports news there, but ex post I should have known that if HP is going to report anything about tennis it is going to be when there was an upset. You won’t see “Federer wins again” there.

Finally, if you really want to keep your prior and you recognize the effects above, then there is one way to generate a countervailing effect. Have your wife watch first and commit to a random disclosure policy. Whenever the favorite won, then with probability p she informs you and with probability 1-p she reveals nothing.

Everyone is jumping on the bandwagon, including Tyler Cowen, Greg Mankiw, and even Sandeep. They are all trumpeting this study whose bottom line is that student evaluations of teachers are inversely related to the teacher’s long-run added value. The conclusion is based on two findings. First, if my students do unusually well in my class they are likely to do badly in their followup classes. Second, if my students evaluate me highly it is likely that they did unusually well in my class.

I am not jumping on the bandwagon. I have read through the paper and while I certainly may have overlooked something (and please correct me if I have) I don’t see any way the authors have ruled out the following equally plausible explanation for the statistical findings. First, students are targeting a GPA. If I am an outstanding teacher and they do unusually well in my class they don’t need to spend as much effort in their next class as those who had lousy teachers, did poorly this time around, and have some catching up to do next time. Second, students recognize when they are being taught by an outstanding teacher and they give him good evaluations.

The authors of the cited study are every time quick to jump to the following conclusion: older, experienced teachers, and especially those with PhD’s know how to teach “lasting knowledge” whereas younger teachers “teach to the test.” That’s a hypothesis that sounds just right to all of us older, experienced teachers with PhD’s. But is it any more plausible than older experienced teachers with tenure don’t care about teaching and as a result their students do poorly? Not to me.

Dear 310-2 students who will be filling out evaluations this week: please don’t hold it against me that I am old, experienced, and have a PhD.

Jonah Lehrer has a post

about why those poor BP engineers should take a break. They should step away from the dry-erase board and go for a walk. They should take a long shower. They should think about anything but the thousands of barrels of toxic black sludge oozing from the pipe.

He weaves together a few stories illustrating why creativity flows best when it is not rushed. This is something I generally agree with and his post is good read but I think one of his examples needs a second look.

In the early 1960s, Glucksberg gave subjects a standard test of creativity known as the Duncker candle problem. The problem has a simple premise: a subject is given a cardboard box containing a few thumbtacks, a book of matches, and a waxy candle. They are told to determine how to attach the candle to piece of corkboard so that it can burn properly and no wax drips onto the floor.

Oversimplifying a bit, to solve this problem there is one quick-and-dirty method that is likely to fail and then another less-obvious solution that works every time. (The answer is in Jonah’s post so think first before clicking through.)

Now here is where Glucksberg’s study gets interesting. Some subjects were randomly assigned to a “high drive” group, which was told that those who solved the task in the shortest amount of time would receive $20.

These subjects, it turned out, solved the problem on average 3.5 minutes later than the control subjects who were given no incentives. This is taken to be an example of the perverse effect of incentives on creative output.

The high drive subjects were playing a game. This generates different incentives than if the subjects were simply paid for speed. They are being paid to be faster than the others. To see the difference, suppose that the obvious solution works with probability p and in that case it takes only 3.5 minutes. The creative solution always works but it takes 5 minutes to come up with it. If p is small then someone who is just paid for speed will not try the obvious solution because it is very likely to fail. He would then have to come up with the creative solution and his total time will be 8.5 minutes.

But if he is competing to be the fastest then he is not trying to maximize his expected speed. As a matter of fact, if he expects everyone else to try the obvious solution and there are N others competing, then the probability is that the fastest time will be 3.5 minutes. This approaches 1 very quickly as N increases. He will almost certainly lose if he tries to come up with a creative solution.

So it is an equilibrium for everyone to try the quick-and-dirty solution, and when they do so, almost all of them (on average a fraction 1-p of them) will fail and take 3.5 minutes longer than those in the control group.

Does it ever happen to you that someone tells you something, then weeks or months pass, and the same person tells you the same thing again forgetting that they already told you before?

Why is it easier for the listener to remember than the speaker? Is there some fundamental difference in the way memory operates? Or is it that the memory is more evocative for the listener just because the fact being told is uniquely associated with the teller? For the person doing the telling you are just a generic listener. Or is it something else? Answer below.

Local surfers jealously guard the best breaks by intimidating non-local interlopers. Here is a paper by Daniel Kaffine that analyzes “localism” as a solution to a commons problem.

I use a unique cross-sectional data set covering 86 surf breaks along the California coast from San Diego to Big Sur to estimate the impact of exogenous wave quality on the strength of informal property rights. In the surfing context, groups of users known as “locals” enforce informal property rights, or localism, in order to reduce congestion from potential entrants, who are denoted “non- locals.” While not recognized legally, user-enforced informal property rights such as localism have features similar to those of formal property rights, such as rules on who may and may not have access to the resource. (“Localism” and “property rights” are used interchangeably throughout this paper.) Surfers in many loca- tions (including California) will tell visitors which breaks are open to anyone and which ones to steer clear of because of localism.

In theory, property rights raise the value of a common resource. But how can this theory be verified in data? The question is confounded by a reverse causality: property rights are more likely to emerge when the resource was already of high value. This data set solves the identification problem.

Unlike frequently studied resources such as fisheries, surf breaks (locations where waves are particularly conducive to surfing) have the feature that wave quality is exogenous with respect to property rights.4 The complex combination of tides, geology, and climatology that lead to high-quality waves would remain unchanged, even under private ownership. Waves do not care if they are ridden or not, which removes the feedback effects between the biophysical and social systems that are present in fisheries, for example. This natural exogeneity isolates the effect of quality in the estimation of its impact on property rights.

The finding is that higher-quality breaks are more likely to give rise to localism. The conclusion:

Thus, studies that attempt to infer the impact of property rights on quality must exercise caution in empirically attributing high resource quality to stronger prop- erty rights. The impact of property rights on resource quality may be overstated if the underlying differences in quality are not controlled for.

Panama pass: orgtheory.net

Affirmative action in hiring is more controversial than it has to be because of the way it is typically framed. People who agree with the general motivation object to specific implementations like racial preferences and quotas because of their blunt nature.

Any affirmative action hiring policy entails a compromise because it mandates a distortion away from the employer’s unconstrained optimal practice. We should look for ways that achieve the goals of affirmative action but with minimal distortions.

One simple idea is turn away from policies that incentivize hiring and instead incentivize search. Suppose that the employer believes that 10% of all candidates are qualified for the job but that only 5% of all minorities are qualified. Imposing a quota on the number of minority hires is less flexible than a quota on the number of minorities interviewed.

Requiring the employer to interview twice as many minority candidates equalizes the probability that the most qualified candidate is a minority or non-minority. Across all employers using this policy, the fraction of minority employees will hit the target. But each individual employer is free to hire the most qualified candidate among the candidates identified so the allocation of workers is more efficient than would be achieved with a straight hiring quota.

That’s the subject of a 2006 paper by Bo Honore and Adriana Lleras-Muney. From the abstract:

In 1971 President Nixon declared war on cancer. Thirty years later, many have declared the war a failure: the age-adjusted mortality rate from cancer in 2000 was essentially the same as in the early 1970s. Meanwhile the age-adjusted mortality rate from cardiovascular disease fell dramatically. Since the causes underlying cancer and cardiovascular disease are likely to be correlated, the decline in mortality rates from cardiovascular disease may in part explain the lack of progress in cancer mortality.

If more people are surviving cardiovascular disease then more will die of cancer. So if there were really no progress in cancer treatment then cancer mortality would in fact be increasing. By how much? That counterfactual question gets at the true benefits of the war on cancer.

In the case of white males, the probability of surviving past age 75 increased by about 19.5 percentage points, from 56.1% in 1970 to 75.6% in 2000. From row 3 [of table 4 in the paper] we see that, in the absence of cancer progress, this probability would have been between 66% and 73.8% in 2000. Therefore from this vantage point progress in cancer ranges from 2 to 10.6 percentage points and accounts for somewhere between 10% and 55% of the total increase in survival.

They identify bounds on cancer progress for other groups as well. The published paper is gated, here is a 2005 working paper version.

What explains Jamiroquai? How can an artist be talented enough to have a big hit but not be talented enough to stay on the map? You can tell stories about market structure, contracts, fads, etc, but there is a statistical property that comes into play before all of that.

Suppose that only the top .0001% of all output gets our attention. These are the hits. And suppose that artists are ordered by their talent, call it τ. Talent measures the average quality of an artist’s output, but the quality of an individual piece is a draw from some distribution with mean τ.

Suppose that talent itself has a normal distribution within the population of artists. Let’s consider the talent level τ which is at the top .001 percentile. That is, only .001% of the population are more talented than τ. A striking property of the normal distribution is the following. Among all people who are more talented than τ, a huge percentage of them are just barely more talented than τ. Only a very small percentage, say 1% of the top .001% are significantly more talented than τ, they are the superstars. (See the footnote below for a precise statement of this fact.)

These superstars will consistently produce output in the top .0001%. They will have many hits. But they make up only 1% of the top .001% and so they make up only .00001% of the population. They can therefore contribute at most 10% of the hits.

The remaining 90% of the hits will be produced by artists who are not much more talented than τ. The most talented of these consist of the remaining 99% of the top .001%, i.e. close to .001% of the population. With all of these artists who are almost equal in terms of talent competing to perform in the top .0001%, each of these has at most a 1 in 10 chance of doing it once. A 1 in 100 chance of doing it twice, etc.

_____________________

(*A more precise version of this statement is something like the following. For any e>0 as small as you wish and y<100% as large as you wish, if you pick x big enough and you ask what is the conditional probability that someone more talented than x is not more talented than x+e, you can make that probability larger than y. This feature of the normal distribution is referred to as a thin tail property.)

A new paper by Bollinger, Leslie, and Sorenson studies Starbuck’s sales data to assess the effects of New York City’s mandatory calorie posting law. Here is the abstract:

We study the impact of mandatory calorie posting on consumers’ purchase decisions, using detailed

data from Starbucks. We find that average calories per transaction falls by 6%. The effect is almost

entirely related to changes in consumers’ food choices—there is almost no change in purchases of beverage calories. There is no impact on Starbucks profit on average, and for the subset of stores located close to their competitor Dunkin Donuts, the effect of calorie posting is actually to increase Starbucks revenue. Survey evidence and analysis of commuters suggest the mechanism for the effect is a combination of learning and salience.

And this bit caught my eye:

The competitive effect of calorie posting highlights the distinction between mandatory vs. voluntary posting. It is important to note that our analysis concerns a policy in which all chain restaurants, not just Starbucks, are required to post calorie information on their menus. Voluntary posting by a single chain would result in substantively different outcomes, especially with respect to competitive effects.

A natural response to these laws is that if it were in the interests of consumers, vendors would voluntarily post calorie counts. But if consumers are truly underestimating calories, then unilateral posting by a single competitor would backfire. Consumers would be shocked at the high calorie counts at Starbucks and go somewhere else where they assume the counts are lower.

Via Robert Wiblin here is a fun probability puzzle:

The Sleeping Beauty problem: Some researchers are going to put you to sleep. During the two days that your sleep will last, they will briefly wake you up either once or twice, depending on the toss of a fair coin (Heads: once; Tails: twice). After each waking, they will put you to back to sleep with a drug that makes you forget that waking.

The puzzle: when you are awakened, what probability do you assign to the coin coming up heads? Robert discusses two possible answers:

First answer: 1/2, of course! Initially you were certain that the coin was fair, and so initially your credence in the coin’s landing Heads was 1/2. Upon being awakened, you receive no new information (you knew all along that you would be awakened). So your credence in the coin’s landing Heads ought to remain 1/2.

Second answer: 1/3, of course! Imagine the experiment repeated many times. Then in the long run, about 1/3 of the wakings would be Heads-wakings — wakings that happen on trials in which the coin lands Heads. So on any particular waking, you should have credence 1/3 that that waking is a Heads-waking, and hence have credence 1/3 in the coin’s landing Heads on that trial. This consideration remains in force in the present circumstance, in which the experiment is performed just once.

Let’s approach the problem from the decision-theoretic point of view: the probability is revealed by your willingness to bet. (Indeed, when talking about subjective probability as we are here, this is pretty much the only way to define it.) So let me describe the problem in slightly more detail. The researchers, upon waking you up give you the following speech.

The moment you fell asleep I tossed a fair coin to determine how many times I would wake you up. If it came up heads I would wake you up once and if it came up tails I would wake you up twice. In either case, every time I wake you up I will tell you exactly what I am telling you right now, including offering you the bet which I will describe next. Finally, I have given you a special sleeping potion that will erase your memory of this and any previous time I have awakened you. Here is the bet: I am offering even odds on the coin that I tossed. The stakes are $1 and you can take either side of the bet. Which would you like? Your choice as well as the outcome of the coin are being recorded by a trustworthy third party so you can trust that the bet will be faithfully executed.

Which bet do you prefer? In other words, conditional on having been awakened, which is more likely, heads or tails? You might want to think about this for a bit first, so I will put the rest below the fold.

If you are one of the millions of Facebook users who play games like Playfish or Pet Society, you are a datum in Kristian Segerstale’s behavioral economics experiments.

Instead of dealing only with historical data, in virtual worlds “you have the power to experiment in real time,” Segerstrale says. What happens to demand if you add a 5 percent tax to a product? What if you apply a 5 percent tax to one half of a group and a 7 percent tax to the other half? “You can conduct any experiment you want,” he says. “You might discover that women over 35 have a higher tolerance to a tax than males aged 15 to 20—stuff that’s just not possible to discover in the real world.”

Note that these are virtual goods that are sold through the game for (literal) money. And here is the website of the Virtual Economy Research Network which promotes academic research on virtual economies.

Jason Kottke tweeted:

Kids, don’t ever aspire to be the world’s oldest person. Have you not noticed that they’re always dying?

which is a good point but I would bet big money that the world’s youngest person dies more often than the oldest.

In a classic experiment, psychologists Arkes and Blumer, randomized theater ticket prices to test for the existence of a sunk-cost fallacy. Patrons who bought season tickets at the theater box office were randomly given discounts, some large some small. At the end of the season the researchers counted how often the different groups actually used their tickets. Consistent with a sunk-cost fallacy, those who paid the higher price were more likely to use the tickets.

A problem with that experiment is that it was potentially confounded with selection effects. Patrons with higher values would be more likely to purchase when the discount was small and they would also be more likely to attend the plays. Now a new paper by Ashraf, Berry, and Shapiro uses an additional control to separate out these two effects.

Households in Zambia were offered a water disinfectant at a randomly determined price. If the price was accepted, then the experimenters randomly offered an additional discount. With these two treatment dimensions it is possible to determine which of the two prices affects subsequent use of the product. They find that all of the variation in usage is explained by the initial offer price. That is, the subjects revealed willingness to pay was the only detrminant of usage and not the actual payment.

This is the cleanest field experiment to date on the effect of past sunk costs on later valuations and it overturns a widely cited finding. On the other hand, Sandeep and I have a lab experiment which tests for sunk cost effects on the willingness to incur subsequent, unexpected, cost increases. We show evidence of mental accounting: subjects act as if all costs, even those that are sunk, are relevant at each decision-making stage. This is the opposite effect found by Arkes and Blumer.

(Dunce cap doff: Scott Ogawa)

The primary rationale for tenure is academic freedom. A researcher may want to pursue an agenda which is revolutionary or offensive to Deans, students, colleagues, the public at large etc. However, the agenda may be valuable and in the end dramatically add to the stock of knowledge. The paradigmic example is Galileo who was persecuted for his theory that the Sun is at the center of our planetary system and not the Earth. Galileo spent the end of his life under house arrest. Einstein considered Galileo the father of modern science. Tenure would now grant Galileo the freedom to pursue his ideas without threat of persecution.

From the profound to the more prosaic: the economic approach to tenure. For economists, tenure is simply another contract or institution and we may ask, when is tenure the optimal contract? My favorite answer to this question is given by Lorne Carmichael’s “Incentives in Academics: Why Is There Tenure?” Journal of Political Economy (1996).

Suppose a university is a research university that maximizes the total quality of research. Let’s compare it to a basketball team that wants to maximize the number of wins. Universities want to hire top researchers and basketball teams want to hire great players. Universities use tenure as their optimal contract but basketball teams do not. Why the difference?

On the basketball side of things it’s pretty obvious. Statistics can help to reveal the quality of a player and you can use the data to distinguish a good player from a bad player. And this can inform your hiring and retention decisions.

On the research side, things are more complicated. Statistics are harder to come by and interpret. On Amazon, Britney Spears’ “The Singles Collection” is #923 in Music while Glenn Gould’s “A State of Wonder: the Complete Goldberg Variations” is #3417. Even if we go down to subcategories, Britney is #11 in Teen Pop and Glenn is #56 in Classical.

So, is Britney’s stuff better than Bach, as interpreted by Glenn Gould? I love “Oops..I did it Again”, but I am forced to admit that others may find Britney’s work to be facile while there is timeless depth to Bach that Britney can’t match.

I’ve tried to offer an example which is fun, but it is also a bit misleading as the analogy with scientific research is flawed. First, music is for everyone, while scientific research is specialized. Second, there is an experimental method in science so it is not purely subjective. But the main point is there is a subjective component to evaluating research and hence job candidates in science. There is less of this in basketball. Shaq is less elegant than Jordan but he gets the job done nonetheless. The subjective component actually matters a lot in science because of the specialization. Scientists are better placed to determine if an experiment or theory in their field is incorrect, original or important. And they are better placed to make hiring decisions, when even noisy signals of publications and citations are not available.

Subjective evaluation is the starting point of Carmichael’s model of tenure. If you are stuck with subjective evaluation, the people who know a hiring candidate’s quality best are people in the department that is hiring him. If the evaluators are not tenured, they will compete with the new employee in the future. If the evaluators hire who is higher quality than they are themselves, they are more likely to get sacked than the person they hire. In fact, the evaluators have the incentive to hire bad researchers so they are secure in their job. This reduces the quality of research coming out of the university. On the other hand, if the evaluator is tenured, their job is secure and this increases their incentive to be honest about candidate quality and leads to better hiring. If there are objective signals as in sport, there is less need for subjective evaluation and hence no need for tenure.

This is the crux of the idea. It is patronizing for anyone to impose their tastes of Britney vs Bach on others. Everyone’s opinion is equally valid. It is possible to say Scottie Pippin was a worse basketball player than Jordan – the data prove it. Science is somewhere in between. There is both an objective component and a subjective component. We then have to rely on experts. Then, the experts may have to be tenured.

OKCupid is a dating site that has attracted attention by analyzing data from its users and publicizing interesting analyses on its blog. For example, a lot of traffic to their site came from this article on the profile photos that generated the most responses.

Mr. Yagan and three other Harvard mathematicians founded OkCupid in 2004. In its fight against much bigger competitors like Match.com, PlentyOfFish and eHarmony, it has tried a number of marketing techniques, often with little success. But the blog, which OkCupid started in October, has helped get the company’s name out on other blogs and social networks. A post last month that set out to debunk conventional wisdom about profile pictures brought more than 750,000 visitors to the site and garnered 10,000 new member sign-ups, according to the company.

But wouldn’t I worry that (my ideal mate would worry that her ideal mate would worry that…) the clientele this will appeal too is a tad too geek-heavy? (via Jacob Grier)

Roland Eisenhuth told me that when he was very young, the first time he had an examination in school his mother told him that she knew a secret for good luck. She leaned in and spit over his shoulder. This would give him an advantage on the exam, she told him.

Indeed it gave him a lot of confidence and confidence helped him do well on the exam. For every school examination after that until he left for University, his mother would spit over his shoulder and he would do well.

Here are the ingredients for a performance-related superstition. Something unusual is done before a performance, say a baseball player has chicken for dinner, and by chance he has a good game. Probably just a fluke. Just in case, he tries it again. Maybe it doesn’t repeat the second time, but maybe he does have another dose of luck and it “pays off” again. And there’s always a chance it repeats enough times in a row that its too unlikely to be a statistical fluke.

Now once you believe that chicken makes you a good hitter, you approach each game with confidence. And confidence makes you a good hitter. From now on, luck is no longer required: your confidence means that chicken dinner correlates with a good game. And you won’t have reason to experiment any further so there will be no learning about the no-chicken counterfactual.

If you are a coach (or a parent) you want to instill superstitions in your student. My wife has been stressing about our third-grade daughter’s first big standardized test coming up in a couple weeks. Not me. I am just going to spit over her shoulder.