You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘art of office politics’ category.

Auctions on eBay have a deadline and aggressive bidding occurs just before the auctions ends. This is called “sniping” (see this excellent paper for a discussion along with the study of many other interesting issues). One reason offered for this behavior is that bids might not come in as the auction ends so if your low bid gets in and my high bid does not, you win anyway (I seem to remember a paper by Al Roth along these lines). A similar effect arises in the debt limit negotiations.

Assume for now the deadline is August 2 – if the debt limit is not raised by then all hell breaks loose. If the House has a proposal on the table later today, this gives the Senate the change to reject it and table their own proposal. But if the House gets their proposal in on August 1, there is too little time left for the Senate to respond with their own bill. If they reject the House proposal, all hell breaks loose. And if the President vetoes the bill, all hell breaks loose. So, there is distinct advantage to the House from delaying the vote. Symmetrically, there is similar advantage to the Senate from delaying the vote. But if both delay the vote, there is also a huge risk that neither proposal makes it through either chamber because both Reid and Boehner are having hard time drumming up enough votes. So, as both parties delay the vote, there is a huge chance of hell breaking loose….

What if the August 2 deadline is not hard? Then, I think I need a model to sort things out but my intuition is that there is bigger incentive to accept an early agreement (after August 1)- if you reject it, there is chance your counter proposal does not make it through as all hell breaks loose because the government runs out of money. But if early agreements might be accepted, there is a bigger incentive to move early and get your bid in…..

Crisis management by firms advises that the firm take blame and apologize for any wrongdoing, create empathy from the consumer, solve any fundamental problem and rebuild reputation and perhaps even achieve competitive advantage. Johnson and Johnson’s strategy when it dealt with arsenic in Tylenol bottles is the “gold standard” of this approach. ( I used to teach this material.) NewsCorp advised by Edelman went some way down this path. Rupert had the most humble day ever and James frequently apologized for the hacking of Milly Dowler’s phone. They shut down the News of the World and “cut out the cancer”. But then tensions emerged between the incentives of the Murdochs and even NewsCorp and the classic crisis management strategy.

First, there were denials that the Murdochs knew anything about the hacking – admitting knowledge would imply there were still cancerous cells left in the NewsCorp organism and these should have also be chopped out. The Murdochs do not want to be chopped out and hence cannot admit to any wrongdoing. Also, if Rupert Murdoch leaves, will NewsCorp survive without the mastermind who created the mega-company? So, blame cannot be taken by Rupert and by blood-relation James. But someone did something wrong even if the Murdochs did not.

This leads to the second problem. The Murdochs have to blame someone for the problems that arose. So far, they have blamed a law firm with which they deposited potentially incriminating emails. A NewsCorp lawyer Tom Crone left and with the closing of NoTW there are may disgruntled staff. The latter have been promised re-employment but it is not clear if this has materialized. Finally, during testimony it emerged that NewsCorp was still paying legal fees for the private investigator at the center of the scandal and they have been forced to withdraw that support – it’s hard to get empathy from consumers if you paying the legals costs of the guy who hacked into Milly Dowler’s phone!

These two forces together mean if there is any collusion between these various players it is close to breaking down. I guess the story will get a second wind despite the beginning of the Parliamentary summer hols. I am not even bringing in the Coulson-Cameron angle which acts as a force multiplier for the story.

Getting from the hotel to Heathrow, we faced the hold-up problem, a fitting end to a trip that began with the Grossman-Hart+25 conference in Brussels. Our cab driver was late picking us up and in compensation the cab company offered us a discount. But when we got to the airport, the cab driver refused to give us the discount saying he knew nothing about it and anyway it was not his fault as he’d been called after the previous driver bailed out. He refused to call his company to confirm my deal and refused to take a credit card (the hotel had told us the cab company would take a credit card if we paid a surcharge of five pounds).

Steam coming out of my ears, I traipsed into the airport and got cash out to pay him. This gave me time to think. The cab driver knew I was not a repeat customer but the cab company was contacted by my hotel and they were definitely hoping to keep the relationship with the hotel going into the future. So I called the hotel which called the cab company which called driver and I got my discount.

Deconstructing this later on, it seemed both I and the cab driver reacted irrationally. Conflict annoys me and the sum involved was trivial. The cab driver would definitely have lost his tip even if I had caved in to his demand so he would not have come out ahead by digging in his heels.

Finally, the cab company may not have set up incentives well with its (subcontracted?) employees. Their incentives are short term and differ from the company’s incentives which are long term. A salary or greater vertical integration rather than payment by commission might dominate. But if people are irrational, the design of the incentive scheme may not help. After all, as I said above, the tip should have provided incentives but it did not.

I am attending a workshop organized by Eli Berman at UCSD. Eli and his co-authors have been studying the military surge in Afghanistan. Colonel Joe Felter, a key member of the research team, presented an overview of the theory of counterinsurgency (COIN) – How can the Afghan government and the US forces “win hearts and minds”?

Think of Apple and Samsung competing for consumers. In the end, a consumer hands over some cash and gets an iPad or a Galaxy. Both sides of the exchange have sealed the deal, an exchange of a product for money. The theory of COIN works the same way. Two potential governments compete for allegiance from an undecided population. They offer them security and public goods in exchange for allegiance. They may also use coercion and violence to compel compliance. There is a key difference – an Afghan citizen can take the goodies offered by the U.S., claim he will offer his allegiance and then withhold it. The exchange takes place over time and there is no “contract” that guarantees payment of allegiance for US bounty.

The Afghans will offer their allegiance to the government that will be around in the long run. And the Taliban tell them, “The Americans have watches but we have the time.” And this strategic issue undercuts the theory of COIN. How can the surge work if one of the firms that is trying to sell you a product won’t be around to honor the warranty?

Downside: It invites Cynicism. Upside: It allows the CEO to make an example of a Cynic and keep other Cynics in line.

Kellogg is raising money for a new building. The Dean and the Great and the Good and doing fundraising. Various committees are in charge of deciding how people should be allocated to offices. Given by lack of political acumen and seniority, I know I will be next to the men’s restroom in the basement. The absence of amy ambiguity about the outcome means I am spending no time agonizing about my decision. But I imagine many of my colleagues are looking at proposed plans and wondering if they can get the corner office. Or will they prefer to be close to friends and co-authors at the cost of giving up a great view of the lake and fit young undergrads playing soccer on the lakeside fields?

Last week’s economic theory seminar speaker, Mariagiovanna Baccara, has a paper with several co-authors that offers an answer. The paper documents the experience of the faculty at an unnamed (but easily guessable) professional school which moved into a new building. The school decided to use a random serial dictatorship mechanism: the professors were split into four equivalence classes by rank (full professors, assistant etc.). Within each class, the order in which each player could choose an office was determined randomly. If there are no externalities, this mechanism achieves an efficient allocation. The first player to move gets the penthouse suite, the second player, the next best corner office etc. But if players care about which players they end up next to, the procedure is not efficient. Each player will not fully internalize the effects of his choice on others.

Before the move, the professors sat within departments and small clusters of like-minded fellow researchers. If the value of this and other networks is small, we would expect players to choose the “room with a view” strategy, picking the best physical location from the remaining offices. The authors compare the allocation that would have resulted if faculty chose offices based on physical characteristics alone with the allocation that actually arose. They find, for example, that co-authors are 36% more likely to be together in the actual allocation that the simulated allocations.

It is possible to estimate network effects a bit better. Aware of the possible inefficiencies of their mechanism, the designers relied on the Coase Theorem to help them out: The mechanism allowed faculty to exchange offices in exchange for cash from their research accounts. If arbitrary exchanges are implemented say between 10 faculty, then ex post exchange will achieve the surplus maximizing allocation. The initial allocation determined via the dictatorship will simply determine the status quo from which bargaining begins but not the final allocation: the famous idea of property right neutrality. But large scale exchanges involve transactions costs and there were few exchanges observed and the ones observed involved two professors. So the authors look at pairwise stable allocations. Combined with various separability assumptions on preferences, this equilibrium notion allows them to estimate network effects. They find co-authorship is more important than department affiliation and friendship. Once these effects are estimated and utilities identified, we can ask the value left on the table by pairwise stable allocations. The authors find an allocation that gives a 183% increases in utility compared to the implemented allocation.

As other schools move buildings, they will use other mechanisms. It will be interesting to study their experience.

You’ve seen Thor, are about to go to the X Men prequel and are waiting to see Captain America. But where is Superman?

It turns out that a copyright issue has bedevilled the Superman character for many years. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster signed away rights to the Superman character to DC comics for $130 over seventy years ago. As the character literally and figuratively took off in the movies and in comic books, Siegel and Shuster got little share in the revenue. But the Copyright Act of 1976 allowed the original owners and their heirs to reclaim ownership if it turned out the value of their invention had become clearer over time and they had been underpaid. Siegel’s heirs used the law to eventually achieve joint ownership in 2008. Since then, investment in the Superman character has languished.

The reasons are simple and are related to the classic hold-up model of Grossman-Hart. Any gain from investment in Superman made by DC Comics will have to be shared with the Siegel heirs. This acts like a tax on investment and hence generates underinvestment. It is better of the ownership is in just one hand. But this amplifies the hold-up problem – it is obvious that DC Comics should own the rights to Superman. After all, they have the expertise in the comic book business and in the brand extensions. But how will they decide the price they will pay the Siegels to get 100% ownership? The present discounted value of the franchise going forward will be the key determinant. Hence, DC Comics (Warner Bros is also involved) have the incentive to destroy the value of the franchise to get a good price. Fans lament that this is what is happening:

Perhaps the most damning part of the decision document was the revelation that executives at Warners shared fans’ cynicism about Superman’s potential (Remember, Warners and DC were the defendants in this case):

Defendants’ film industry expert witness, Mr. [John] Gumpert, termed Superman as “damaged goods,” a character so “uncool” as to be considered passe, an opinion echoed by Warner Bros. business affairs executive, Steven Spira… Indeed, Mr. [Alan] Horn [Warner Bros. President] admitted to being “daunted” by the fact that the 1987 theatrical release of Superman IV had generated around $15 million domestic box office, raising the specter of the “franchise [having] played out.”

Almost as surreally, DC and Warners apparently argued to the court that

Superman was equivalent [in terms of public recognition and financial value] to a low-tier comic book character that appeared mostly on radio during the 1930s and 1940s and that has not been seen since a brief television show in the mid-1960s (the Green Hornet); an early 20th century series of books (Tarzan) or a 1930s series of pulp stories (Conan) later intermittently made into comic books and films; or a television, radio, and comic book character from the 1940s and 1950s, much beloved by my father, that long ago rode off into the proverbial sunset with little-to-no exploitation in film or television for decades (The Lone Ranger).

And these are the people in charge of the character?!?

(Hat Tip: Scott Ashworth)

In the New Yorker, Lawrence Wright discusses a meeting with Hamid Gul, the former head of the Pakistani secret service I.S.I. In his time as head, Gul channeled the bulk of American aid in a particular direction:

I asked Gul why, during the Afghan jihad, he had favored Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, one of the seven warlords who had been designated to receive American assistance in the fight against the Soviets. Hekmatyar was the most brutal member of the group, but, crucially, he was a Pashtun, like Gul.

But

Gul offered a more principled rationale for his choice: “I went to each of the seven, you see, and I asked them, ‘I know you are the strongest, but who is No. 2?’ ” He formed a tight, smug smile. “They all said Hekmatyar.”

Gul’s mechanism is something like the following: Each player is allowed to cast a vote for everyone but himself. The warlord who gets the most votes gets a disproportionate amount of U.S. aid.

By not allowing a warlord to vote for himself, Gul eliminates the warlord’s obvious incentive to push his own candidacy to extract U.S. aid. Such a mechanism would yield no information. With this strategy unavailable, each player must decide how to cast a vote for the others. Voting mechanisms have multiple equilibria but let us look at a “natural” one where a player conditions on the event that his vote is decisive (i.e. his vote can send the collective decision one way or the other). In this scenario, each player must decide how the allocation of U.S. aid to the player he votes for feeds back to him. Therefore, he will vote for the player who will use the money to take an action that most helps him, the voter. If fighting Soviets is such an action, he will vote for the strongest player. If instead he is worried that the money will be used to buy weapons and soldiers to attack other warlords, he will vote for the weakest warlord.

So, Gul’s mechanism does aggregate information in some circumstances even if, as Wright intimates, Gul is simply supporting a fellow Pashtun.

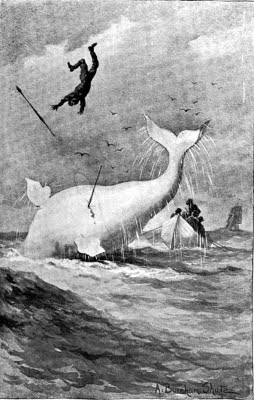

Hamlet: Do you see yonder cloud that’s almost in the shape of a camel?

Polonius: By the mass, and ’tis like a camel, indeed.

Hamlet: Methinks it is like a weasel.

Polonius: It is backed like a weasel.

Hamlet: Or like a whale? Polonius: Very like a whale.-William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 2

For most of your career, you have toiled away getting bonuses, stock options and the like. Your CEO believes in pay for performance and the data says you have performed so you have been paid. You are so successful that promotion beckons – the CEO appoints you to a senior position, advising her on key investments your firm must make to expand. She has her eye on building a new factory in Shanghai and she asks you to look into it. The investment might be good or bad. Your hard work collecting data on potential demand and costs will help to inform the decision. But there is a key difference. In your old job, your hard work led to higher measurable profit and you were paid for performance. In your new job, information acquisition might as well lead to a signal that the investment is bad as to signal that it is good. In other words, a bad signal does not signal that you did not collect information while bad performance is your old job was a signal that you were not working hard. How can the CEO reward pay for performance in your new job?

Since there is no objective yardstick, the CEO must rely on a subjective performance measure. Your pay will depend on a comparison of your report with the CEO’s own signal. The problem arises if you get a noisy signal of the CEO signal. Then you have a noisy assessment of what she believes and hence a noisy signal of how your report will be judged and hence renumerated. In equilibrium, you will condition your report not only on your signal but also on your signal of the CEO’s signal. You are a “yes man”. The yes man phenomenon arises not from a desire to conform but from a desire to be paid! Prendergast uses this idea as a building block to study many other topics including incentives in teams. The greater the level of joint decision-making, the problematic is the yes man effect. He points out that if the CEO asks you to back up your opinion with arguments and facts, this mitigates the yes man effect. Plus he has the great quote above at the start of his paper.

The members of a firm must work together on a big joint project. There are many ways the project could be implemented. One obvious procedure is dictatorial: the CEO simply choses her favorite option and demands that everyone follow her orders. This is sometimes called directive or narcissistic leadership. Another procedure is more participative: The CEO asks everyone their opinion and a decision is made. Everyone might vote so the decision is made democratically or at the very least the CEO makes everyone’s opinions into account before making the decision herself.

In an emergency situation where decisions need to be made quickly, dictatorial leadership makes sense. If you are in the middle of capturing Bin Laden, there is no time to mess around with participative leadership. One person gives orders and everyone follows.

But in many other situations, it is wise to ask everyone’s opinions before embarking on a joint project. The obvious rationale is that information is dispersed and communication might help to aggregate information. The less obvious reason (to economists!): If people do not feel they “buy into” the decision, they are not going to work hard. There may be no information to aggregate but the mere fact that everyone votes means that even the minority who voted against the decision feel committed to it.

A firm is thinking about making a huge new investment. After consultation and deliberation, the CEO and the employees unanimously decide the project should go ahead and initial investment begins. As time passes more and more members of the organization realize that the investment is not a good idea after all. It is better to cut and run. Some costs are sunk and the NPV looking forward is negative.

The CEO is in charge of the continuation decision but his incentives are not aligned with the organization’s. Privately, he was actually reluctant to pursue the project. Publicly, he boasted about the investment, how great it was all going to be, how great the firm would be when the investment paid off. The CEO cannot go back on his word. The market will judge him purely on whether the investment is made and whether it pays off. He cannot cancel the project and instead he forces it through. If it pays off, his career takes off; if it fails, his career is a shambles but is is also in a tailspin if he cancels the project. The employees watch anxiously. They will give him a year and if nothing works, they will look for opportunities elsewhere.

An unusual coalition has developed at New York Times op-ed meetings – sworn enemies libertarian Tyler Cowen and socialist Paul Krugman have banded together to oppose the new NYT paywall. Cowen and Krugman could not be further apart philosophically.

An ardent believer in the esoteric “Coase Theorem”, Cowen opposes all government intervention except to enforce property rights.  He believes everything else can be “left to the market” and “rational agents will negotiate their way to the efficient frontier”. Krugman is now a behavioral economics fanatic. To Krugman, rational agents are some hypothetical ideal that is never seen in the “real world”. If people make mistakes, a government or a super-intelligent being – as Krugman believes himself to be – can make decisions on their behalf. Hence, the Nobel Prize winner thinks consumers, firms, banks, investors, in fact pretty much anybody should be pushed not nudged into making good decisions. Indeed, Krugman is writing a new book “Shove” to act as a counterpoint to the milder forms of intervention proposed by the Chicago School of Behavioral Economics.

He believes everything else can be “left to the market” and “rational agents will negotiate their way to the efficient frontier”. Krugman is now a behavioral economics fanatic. To Krugman, rational agents are some hypothetical ideal that is never seen in the “real world”. If people make mistakes, a government or a super-intelligent being – as Krugman believes himself to be – can make decisions on their behalf. Hence, the Nobel Prize winner thinks consumers, firms, banks, investors, in fact pretty much anybody should be pushed not nudged into making good decisions. Indeed, Krugman is writing a new book “Shove” to act as a counterpoint to the milder forms of intervention proposed by the Chicago School of Behavioral Economics.

Naturally, op-ed meetings were quite lively with these two extremists in the same virtual room via Skype. But NYT Editor Bill Keller and owner Arthur Sulzberger are looking back at those meetings with misty eyed nostalgia now Cowen and Krugman have ganged up. Both commentators are hopping mad about the paywall but for quite different reasons.

Libertarian Cowen thinks his column belongs to him and that the NYT has violated his property rights by making money from his columns without compensating him. Also, he and Alex Tabarrok have a highly successful website, Marginal Revolution, which is free. Cowen makes money from the advertising the site carries as well as from speaking gigs his fame generates. His free-up-till-now column for the NYT was another part of this business model.

Krugman has quite different motives. Most importantly, he simply wants his radical message to get out to as wide an audience as possible. A paywall might stop that. Second, Krugman is obsessed with the size of his readership. In the internal impact ratings followed at newspapers, the newspaper equivalent of Google Scholar, Krugman is number one. But the paywall might allow his archenemy George Will at the (free-after-you-register) Washington Post to leap ahead.

So, Cowen and Krugman are planning a Twitter-murder of the NYT paywall. Each will link to NYT articles in Twitter messages and send them to vast legions of loyal followers. These links are free and subvert the entire logic of the paywall. They may overwhelm traffic at the NYT. If Twitter can get rid of a dictator in Egypt, surely it can tear down a paywall.

The TV channel AMC has a huge critical hit, the show “Mad Men”, on its hands. It’s never been clear how much money they make of the show – a critical hit is not necessarily an audience hit. They are trying to make more money by cutting the budget and the length of the show and putting in ads. The show’s creator Matt Weiner is having none of it. Both sides have dug in their heels and there is a war of attrition. Inside reports suggest:

“Weiner may just walk away from the show and the AMC execs are threatening to go ahead with Mad Mean without Weiner”

Neither side has a fully credible threat. Weiner loves his show too much to walk way from it and AMC needs the show as it put the channel on the map.

Both sides need to work on their outside options. Weiner should talk to HBO which is kicking itself for turning down the show years ago. AMC has an option on the show for one more year but then all bets are off. Who knows how ambiguous AMC’s option on Mad Men is. Maybe the show’s name can be changed and the whole thing can move with a new name to HBO.

Negotiating advice is harder to offer to AMC. Do they have great shows right now or in the planning stage they can slot into the Mad Men time slot? They can threaten to do the show without Weiner but if the actors and writer/director leave, is it really going to draw in an audience or the critics?

The now metered and paywall protected NYT reports:

The Obama administration is engaged in a fierce debate over whether to supply weapons to the rebels in Libya, senior officials said on Tuesday, with some fearful that providing arms would deepen American involvement in a civil war and that some fighters may have links to Al Qaeda.

Why?

Even if fighters do not have links to Al Qaeda or Hezbollah, what is there to guarantee that they are or will remain friendly to the Western allies? Gaddafi while historically unfriendly had finally been seduced with Mariah Carey concerts and Coca Cola. Arming the rebels might fulfill a short term objective of regime change but at the cost of creating an armed future enemy. What’s the debate?

This is an easy one: North Korea thinks (1) the US is out to exploit and steal resources from other countries and hence (2) Libya was foolish to giving away its main weapon, its nascent nuclear arsenal, which acted as a deterrent to American ambition. Accordingly,

“The truth that one should have power to defend peace has been confirmed once again,” the [North Korean] spokesperson was quoted as saying, as he accused the U.S. of having removed nuclear arms capabilities from Libya through negotiations as a precursor to invasion.

“The Libyan crisis is teaching the international community a grave lesson,” the spokesperson was quoted as saying, heaping praise on North Korea’s songun, or military-first, policy.

In a perceptive analysis, Professor Ruediger Franks adds two more examples that inform North Korean doctrine. Gorbachev’s attempts to modernize the Soviet Union led to its collapse and the emancipation of its satellite states. Saddam’s agreement to allow a no-fly zone after Gulf War I led inexorably to Gulf War II and his demise. The lesson: Get more nuclear arms and do not accede to any US demands.

Is there a solution that eliminates nuclear proliferation? Such a solution would have to convince North Korea that their real and perceived enemies are no more likely to attack even if they know North Korea does not have a nuclear deterrent. Most importantly, the US would have to eliminate North Korean fear of American aggression. In a hypothetical future where the North Korean regime has given up its nuclear arsenal, suppose the poor, half-starved citizens of North Korea stage a strike and mini-revolt for food and shelter and the regime strikes back with violence. Can it be guaranteed that South Korea does not get involved? Can it be guaranteed that Samantha Power does not urge intervention to President Obama in his second term or Bill Kristol to President Romney in his first? No. So, we are stuck with nuclear proliferation by North Korea. The only question is whether North Korea can feel secure with a small arsenal.

Tomas Sjostrom and I offer one option for reducing proliferation in our JPE paper Strategic Ambiguity and Arms Proliferation. If North Korea can keep the size and maturity of its nuclear arsenal hidden, we can but guess at its size and power. It might be large or quite small – who knows. This means even if the arsenal is actually small, North Korea can still pretend it is big and get some of the deterrent power of a large arsenal without actually having it. The potential to bluff afforded by ambiguity of the size of weapons stockpiles affords strategic power to North Korea. It reduces North Korea’s incentive to proliferate. And this in turn can help the U.S. particularly if they do not really want to attack North Korea but fear nuclear proliferation. Unlike poker and workplace posturing à la Dilbert, nuclear proliferation is not a zero-sum game. Giving an opponent the room to bluff can actually create a feedback loop that helps other players.

The forward looking agent forecasts trends in consumer demand, spots market opportunities and readies his organization for a great leap forward. But any decision is plagued with unforeseen contingencies. By necessity, any agent must also be backward looking, putting our fires as they appear. This sucks attention from looking forward and the organization may atrophy and lose its edge.

These two extremes manifest themselves in different ways at different points in an organization’s history. A firm that is just starting out will be forward looking by definition. There is no history, no fires to put out. Either the young firm dies – its products are unpopular – or it succeeds. That’s when the trouble starts. Success also breeds emergencies and crises large and small. Now attention is diverted. A young organization that reaches middle age it may not survive into old age. If optimization of extant decisions is the main activity, there is no time left to prepare for the next wave of technology, consumer demand…etc.

If the organization reaches old age, it is because it has learned to deal with unforeseen contingencies. It has set up frameworks, codes of practice and procedures that can simply be activated when a fire appears. This creates room for forward looking strategy analysis.

To summarize, a young organization is more forward-looking than a middle-aged organization. An old organization may also be more innovative than a middle-aged organization. We do not have a way to rank young and old organization with this bare-bones theory. There are, of course, many other theories. The “replacement effect” is one obvious alternative.

There are many dimensions to this question . Let me focus on just one – collective decision-making.

Say there are two well-defined groups, A and B, in the division doing related but different work. Group A cannot judge collective decisions on hiring, investment etc that impinge on Group B and vice-versa. But the members of Group A certainly have opinions on how they should hire, fire and invest in their own group and so does Group B. Suppose the two groups vote together on all decisions within the division even if they mainly concern one group and not the other. There are two polar cases.

The members of each group have near common values and want pretty much the same thing. Then voting by each group on its own decisions aggregates information. The uninformed group should abstain. And if there are collective decisions that must be made at the division level, there is no need to break the group up.

At the other extreme, suppose for instance there is serious disagreement in Group A – there are significant private values. The members of Group B also get weak signals of the best decision for Group A. There is also a seniority ranking over the members of Group A. If the members of Group B continue to abstain on all Group A decisions, then information is still aggregated.

But there is another possibility. Members of Group B want to curry favor with senior members of Group A. These senior members are involved in lots of firm level decisions and it is important to have them on board. Then, another equilibrium can develop. When Group B member think the senior members of Group A are wrong, they abstain. They think their signals are too weak to overrule Group A members. But if they think the senior members of Group A are right, they vote enthusiastically along with them. Career concerns screw up voting in the division. This division should be broken up.

You are reorganizing your firm. There are many legacy employees the old CEO was too weak to fire. They are inefficient and incompetent but their connection to the old CEO – an insider – kept their jobs safe. You were hired from the outside and feel no particular affection for the old guard. There is one employee Mr X who is high up. He is terrible at his job but has survived by using his charm and by buttering up the customers. Sometimes he went too far. You hear rumors of “liasons” between your staff and the customers. Also, there were inappropriate exchanges of gifts. While nothing was strictly illegal, if news gets out, your firm will look bad and business will suffer.

You are reorganizing your firm. There are many legacy employees the old CEO was too weak to fire. They are inefficient and incompetent but their connection to the old CEO – an insider – kept their jobs safe. You were hired from the outside and feel no particular affection for the old guard. There is one employee Mr X who is high up. He is terrible at his job but has survived by using his charm and by buttering up the customers. Sometimes he went too far. You hear rumors of “liasons” between your staff and the customers. Also, there were inappropriate exchanges of gifts. While nothing was strictly illegal, if news gets out, your firm will look bad and business will suffer.

You want to sack Mr X. Your problem is that he knows too much: if you fire him, he threatens to go to the press and tell them everything he knows. This would be a catastrophe. One thing can save you: what is bad for you is also bad for him. Mr X played no small part in the sleazy business he threatens to reveal. He’ll have a hard time getting a new job if he spills the beans. Even if he gets a new job, stabbing is old boss in the back will make his new boss worry if he can trust Mr X. It seems you are safe.

What can Mr X do to make his threat credible? This is an classic problem in game theory and perhaps I have something new to say. But it cannot be better than what Schelling and Ellsberg said many years ago. For example, see the Theory and Practice of Blackmail by Daniel Ellsberg. Ellsberg identifies four strategies for the blackmailer: (1) commitment, (2) contracts with third parties, (3) uncertainty about payoffs and (4) cultivating a reputation for irrationality.

Mr X might give his evidence over to a lawyer and instruct him to release it should Mr X ever be fired. He might write a contract with a third party stipulating that he will pay a large fine to the third party if Mr X is fired and does not release the evidence. These solutions seem far fetched to Mr X. He has no wealth to hand over as a fine and anyway contracts can be renegotiated (e.g. The third party knows that he will not get paid in equilibrium. So Mr X and the third party could agree to write a new contract after Mr X is fired. The agree to small payment to the third party even if Mr X does not reveal the evidence.)

So, Mr X is left with the last two options which are quite related. He has to look either as if he enjoys a fight for its own sake or that he does not but is crazy enough to take actions against his own self-interest. The topic of many subsequent papers in game theory.

Ellsberg’s paper is the text of a lecture he gave to a general interest audience. It is an easy and fun read. Ellsberg offers a very clear definition of rationality as used in economics. The paper is notable for an aesthetic in game theory that it espouses: Game theory offers qualitative intuition and is not inherently quantitative. And it is an art not a science.

Malcolm Gladwell is cynical about the ability of social media to facilitate activism:

The platforms of social media are built around weak ties. Twitter is a way of following (or being followed by) people you may never have met. Facebook is a tool for efficiently managing your acquaintances, for keeping up with the people you would not otherwise be able to stay in touch with. That’s why you can have a thousand “friends” on Facebook, as you never could in real life

If Twitter is only identifying people with weak preferences for activism, the “revolution will not be tweeted”. But there is a second countervailing effect created by network externalities, studied in Gladwell’s book The Tipping Point. An individual’s cost in participating in a revolution is s function of how many other people are involved. For example, the probability that an individual gets arrested is smaller the larger the number of people surrounding him in a demonstration. Even if Twitter in the first instance does not increase the number of people participating in a demonstration, it does create common knowledge about where they are meeting and when. The marginal participant in the absence of common knowledge strictly prefers to participate with Twitter-common-knowledge. Now more individuals will join as the demonstration has gotten a bit bigger etc. The twitting point is reached and we have a bigger chance of revolution. Now, let me go to Jeff’s twitter feed and see what he is plotting in his takeover of the NU Econ Dept.

There is pressure for filibuster reform in the Senate. Passing the threshold of sixty to even hold a vote was hard in the last couple of years when the Democrats had a large majority. It’s going to be near impossible now their ranks are smaller. Changing the rules has a short run benefit – easier to get stuff passed – but a long run cost – the Republicans will use the same rules to pass their legislation when Sarah Palin is President. Taking the long view, the Democrats decided not to go this route.

By the same token, the kind delaying tactics that did not work in the lame duck session are an efficiency loss – they had little real effect on legislation but delayed the Senators taking the kind of long holidays they are used to. Some movement on delaying tactics is mutually beneficial. And so according to the NYT:

“Mr. Reid pledged that he would exercise restraint in using his power to block Republicans from trying to offer amendments on the floor, in exchange for a Republican promise to not try to erect procedural hurdles to bringing bills to the floor.

And in exchange for the Democratic leaders agreeing not to curtail filibusters by means of a simple majority vote, as some Democratic Senators had wanted to do, Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the Republican leader, said he would refrain from trying that same tactic in two years, should the Republicans gain control of the Senate in the next election.”

I am teaching a new PhD course this year called “Conflict and Cooperation”. The title is broad enough to include almost anything I want to teach. This is an advantage – total freedom! – but also a problem – what should I teach? The course is meant to be about environments with weak property rights where one player can achieve surplus by stealing it and not creating it. To give some structure, I have adopted Hobbes’s theories of conflict to give structure to the lectures. Hobbes says the three sources of conflict are greed, fear and honour. The solution is to have a government or Leviathan which enforces property rights.

Perhaps reputation models à la Kreps-Milgrom-Roberts-Wilson come closest to offering a game theoretic analysis of honour (e.g. altruism in the finitely repeated prisoner’s dilemma). But I will only do these if I get the time as this material is taught in many courses. So, I decided to begin with greed.

I started with the classic guns vs butter dilemma: why produce butter when you can produce guns and steal someone else’s butter? This incentive leads to two kinds of inefficiency: (1) guns are not directly productive and (2) surplus is destroyed in war waged with guns. The second inefficiency might be eliminated via transfers (the Coase Theorem in this setting). This still leaves the first inefficiency which is similar to the underinvestment result in hold-up models in the style of Grossman-Hart-Moore. With incomplete information, there can be inefficient war as well. A weak country has the incentive to pretend to be tough to extract surplus from another. If its bluff is called, there is a costly war. (Next time, I will move this material to a later lecture on asymmetric information and conflict as it does not really fit here.)

These models have bilateral conflict. If there are many players, there is room for coalitions to form, pool guns, and beat up weaker players and steal their wealth. What are stable distributions of wealth? Do they involve a dictator and/or a few superpowers? Are more equitable distributions feasible in this environment? It turns out the answer is “yes” if players are “far-sighted”. If I help a coalition beat up some other players, maybe my former coalition-mates will turn on me next. Knowing this, I should just refuse to join them in their initial foray. This can make equitable distributions of wealth stable.

I am writing up notes and slides as I am writing a book on this topic with Tomas Sjöström. Here are some slides.

The WSJ Ideas Market blog has a post by Chris Shea about my forthcoming paper with David Lucca (NY Fed) and Tomas Sjöström. (Rutgers) Some excerpts:

Full democracies are unlikely to go to war with one another. That’s axiomatic in political science. Yet a new study offers an important caveat: Limited democracies may, in fact, be even more bellicose than dictatorships…….

The authors end with a twist on President George W. Bush’s contention that “the advance of freedom leads to peace”: “Unfortunately,” they say, “the data suggests that this may not be true for a limited advance of freedom.”

Here is another article in Kellogg Insight about the paper.

As the junior job market rears it ugly head, there are many deep questions: How good are the candidates’ papers? If the papers are so-so, do the candidates show signs of promise and potential for good work in the future? Is there a forgiving, omniscient God? I digress but you get the picture – I have no easy answers for the deep questions. But I do have trite answers for shallow questions.

So, let us turn to “job market meal,” the mating dance that usually ends the visit.

Let us first consider dinner planning. If I am in charge of organizing the visit, I find it is imperative to have my ducks lined up before hand, i.e. get the dinner party and restaurant fixed ahead of the visit. Otherwise, there can be a nightmare scenario where the candidate visit is a disaster, no-one else wants to go to dinner and you are stuck as a silent, unromantic twosome at a pizza joint close to work.

The now planned-ahead restaurant choice is a delicate matter. Like a date, you are sending a signal about how much you care via the restaurant choice. You might like the pizza joint and the very fact you are going to dinner with a spouse and kids at home is a costly signal of your interest. But the people you are interviewing are young and have no knowledge of spouses and kids. Your signal has to be more obvious so you have to go to an (obviously) good restaurant.

There is another dangerous mistake you can make at this step: choosing a restaurant that is too good. This carries a double risk. First, you are sending a confused signal: Is this dinner really signaling your interest in the candidate or in an expensive meal subsidized by your university? Second, and in my experience more pertinently, you are subject to the wonderful but confusing impact of the melting pot that is the American job market for economists. Students from all over the world get into PhD programs at American universities and if their papers are good, they can get a job anywhere. As one of the melty bits in the pot, I can’t help but celebrate this but it does lead to some confusion at the dinner table. Is some hardworking nerd from a land-locked country really going to appreciate the raw seafood at the Temple to Sushi you decide to go to? Chances are that they have been stuck in front of a computer eating toast and processed cheese for the last five years and, before that, they’d never heard of high or low grade tuna.

Play it safe: a good Italian or French restaurant is the best choice.

Liberal commentators bemoan the demise of the old John McCain they thought they knew and loved. Joe Klein wonders what happened to the guy who originally sponsored the Dream Act to allow children of illegal immigrants to become citizens. Think Progress points out that he is now supporting the tax cuts to the rich he vilified in 2000-2004. What has happened to John McCain? Have his preferences changed?

Liberal commentators bemoan the demise of the old John McCain they thought they knew and loved. Joe Klein wonders what happened to the guy who originally sponsored the Dream Act to allow children of illegal immigrants to become citizens. Think Progress points out that he is now supporting the tax cuts to the rich he vilified in 2000-2004. What has happened to John McCain? Have his preferences changed?

There is one obvious theory that seems to make his positions consistent: McCain had to run to the right to beat off a primary challenger in Arizona. But, as Joe Klein points out, “he recently won reelection and doesn’t have to pretend to be a troglodyte anymore.” So this theory is flawed.

There is another obvious theory. In this one, you have to identify an outcome a person supports or opposes not just by the policy itself but also by the the other person who supports it. So you have outcomes like “tax policy opposed by Obama,” “tax policy supported by Bush,” “tax policy supported by Obama,” “tax policy opposed by Bush” etc. Then, it is quite consistent for McCain to support a 35% tax on the rich when Bush opposes it but to oppose a 35% tax on the rich when Obama proposes it. Essentially, if McCain loses to someone in a Presidential election or primary he opposes their policies whatever they are.

A sophisticated model along these lines is offered by Gul and Pesendorfer. It allows one person’s preferences to depend on the “type” of the other person, e.g. is the opponent selfish or generous? In principle, this model allows us to determine whether a person is spiteful using choice data. McCain certainly has some behavior that is consistent with spitefulness. Is he ever generous? We would need to know his choices when facing someone he beat in a contest or someone he has never played. Or is he just plain mean? Joe Klein leans towards spite based on the available data:

“He’s a bitter man now, who can barely tolerate the fact that he lost to Barack Obama. But he lost for an obvious reason: his campaign proved him to be puerile and feckless, a politician who panicked when the heat was on during the financial collapse, a trigger-happy gambler who chose an incompetent for his vice president. He has made quite a show ever since of demonstrating his petulance and lack of grace.

What a guy.”

If choice with interdependent preferences can be utilized in empirical/experimental analyses, we can investigate the soul of homo economicus using the revealed preference paradigm.

One activity can equally be done by Division A or Division B of a firm but, for historical reasons, Division A has control of it right now. This gives the managers of Division A lots of power to hire and they like having a little empire. But the CEO comes up with a plan: Since both divisions are in theory up to the job, have them compete for the activity.

The best way to do this is pretty obvious: If Division A screws up, give the job to Division B. But of Division A does a good job let them keep it. This gives Division A good incentives to work hard to do a good job.

In practice it is hard to measure the quality of output so it is hard to implement this simple scheme. Quality is evaluated by subjective judgements and rhetorical arguments. Perversely, the better the job Division A is doing, the more incentive Division B has to try to steal the job. This is because a job well done generates lots of slots. If Division A is doing a bad job, the activity does not look worth stealing.

So, in practice, having the divisions compete for the activity can lead to destruction of incentives. Better to give one division the property right over the activity and intervene only when outcomes are objectively poor.

We dress like students, we dress like housewives

or in a suit and a tie

I changed my hairstyle so many times now

don’t know what I look like!

Life during Wartime, Talking Heads

Mr C. is the new C.E.O. of your firm, Firm C. He was head of operations at one of your competitors Firm A. He was passed over for promotion there and had to exit to get to the C Suite. You wonder about the wisdom of your Board: Why would they choose someone who rejected for the top job by their own company? You subscribe the “Better the Devil you know, than the Devil you don’t” principle. If your firm appoints an internal person to the top job, at least you know their flaws and can adapt to them. This principle also applies at Firm A. So, if they rejected the Devil they know, he must be a really terrible Devil or, to put it in tamer economic terms, a “lemon.”

But you are also aware of the counter argument: Real change can only be achieved by an outsider. Mr C said some smart things in the interview process and so you are happy to give him the benefit of the doubt. You are expecting Mr C. to define a mission for Firm C, a mission that everyone can sign on to. Of course, to persuade everyone to work hard on the vision it has to be a “common value” – something everyone agrees is good – not a “private value” – something only a subgroup agrees is good. In this regard, Mr. C surprises you – he makes a big play that Operations are the most important thing in a successful firm. “Look at H.P. and Amazon,” he says. “They don’t actually make anything, just move stuff around efficiently and/or put in together from parts they buy from other firms. We need innovation in Operations not fundamental innovation in our product line.”

You are shocked. Your firm has R and D Department that has produced amazing, fundamental innovations. Innovative ability is sprinkled liberally throughout your firm in – it is famous for it. It is a core strength of Firm C. Why would anyone want to destroy that and focus on Operations? What should do you do? In times of trouble, you have a bible you turn to – Exit, Voice and Loyalty by Albert Hirshman

Should you give voice to your concerns? The last CEO ignored you and the new CEO might give you more attention so you had thought that you might talk to him. But your first impressions are bad and something you might say might be misinterpreted and lead to the opposite conclusion in the mind of the new CEO. Talking is dangerous anyway. You might be identified as a troublemaker and given lots of terrible work to do. Better to keep quiet and blend in with the crowd.

Is loyalty enough to keep you working hard anyway? Your firm is not a non-profit and, given the CEO plans to quash innovation, it is basically going to produce junk. Why should anyone be loyal to that?

You are drawn inexorably to Hirshman’s last piece of advice: exit. This is hard during the Great Recession – there are few jobs going around. You will be joined by all those who can exit from your sinking ship C so you have to move fast….

From Bloomberg (the firm not the man):

New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who has been mentioned as a potential U.S. presidential candidate, said he doesn’t believe an independent can win.

Bloomberg, who isn’t affiliated with Republicans or Democrats, said a candidate running outside the two-party system couldn’t get a majority of the 538 votes in the Electoral College, which would trigger a provision in the U.S. Constitution giving the House of Representatives power to decide the election.

“Unless you get a majority, it goes to the House,” he said today during a conference sponsored by the Wall Street Journal in Washington. “It’s going to go to the Republicans because the Republicans have just taken over the House.”

I guess billionaires can do backward induction. If only people who can do backward induction were billionaires….

As junior recruiting approaches, we cannot help but speculate on the optimal way to compare apples to oranges – candidates across different fields (e.g. micro vs macro) and across universities. I speculated a while ago that a “best athlete” recruiting system across fields is prone to gaming. Each field might simply claim its candidate is great. To stop that happening, you might have to live with having slots allocated to fields and/or rotating slots over time.

It turns out that Yeon-Koo Che, Wouter Dessein and Navin Kartik have thought about something much more subtle along these lines in their paper “Pandering to Persuade“. They consider both comparisons across fields and across candidates from different universities. I’m going to give a rough synopsis of the paper.

Suppose the recruiting committee in an economics department is deciding whether to hire a theorist or a labor economist. There is only one labor economist candidate and her quality is known. There are two theorists, one from University A and one from University B. The recruiting committee would like to hire a theorist if and only if his quality is higher than the labor economist’s. Also, the recruiting committee and everyone else believes that, on average, candidates from University A are better than those from University B. But of course this is only true on average. Luckily some theorists can read the paper and help fine tune the committee’s assessment of the theory candidates. They share the committee’s interest in hiring the best theorist but they are quite shallow and hence uninterested in research outside their own field. In particular, theorists do not care for labor economics and always prefer a theorist at the end of the day.

So, the recruiting committee must listen to the theorists’ recommendation with care. First, the theorists have huge incentives to exaggerate the quality of their favored candidate if this carries influence with the committee. Hence, quality evaluations cannot be trusted. All the theorists can credibly do is say which candidate is better but not by how much. But there is a further problem: if the theorists say candidate B is better, given the committee’s prior, they might think better of candidate B and yet prefer to hire the labor economist! Being theorists, the sender(s) can do backward induction and they know the difficulty with their strategy if it is too honest. The solution is obvious to the theorists: extol the virtues of candidate A even when candidate B is a little better. Hence, in equilibrium, the candidate from the ex ante better university gets favored. But candidate B still has a shot: if they are sufficiently good, the theorists still recommend them. The committee may with some probability still go with the labor economist so it is risky to make this recommendation. But if candidate B is sufficiently good, the theorists may want to run this risk rather than push the favored candidate A. I refer you to the paper for the full equilibrium(a) but, as you can see, the paper is fun and interesting.

There are some extensions considered. In one, the authors study delegation to the theorists. Sometimes the department will lose out on a good labor economist but at least there is no incentive for the theorists to select the worst candidate. This is the giving slots to fields solution I wondered about and it is derived in this elegant model.

Advice before tenure is some variation around a cliché: Publish or Perish! Some universities may assess impact or make their own subjective evaluation of your work, believing that they have the taste and scientific expertise to do so. Others may have a more quantitative approach, counting papers, ranking journals and adding up citations. But if you haven’t published, basically you are going to perish.

Suppose you get tenure. You overcome your feeling of ennui and the “Is this all there is?” existential crisis. You accept the fact that you are probably going to be stuck with the same people for another 30-35 years. You publish the stuff that was in the pipeline when you came up for tenure. What do you do next?

When I have personal dilemmas of this sort, I try to find some wise women to help me out. For the post-tenure dilemma, I turned to the Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession (CSWEP). Their Winter 2009 issue has lots of useful articles. This is several years after my tenure but it turns out I was instinctively following much of the advice anyway. For example, Bob Hall says in his article:

“Now that you have tenure, the number of papers you produce is amazingly irrelevant. One good paper a year

would put you at the very top of productivity. Consequently, you should generally spend your research time on the most

promising of the projects you are working on. A related principle is that you should try to maintain a lot of slack in

your time allocation, so that if a great research idea pops into your head or a great opportunity comes along in another

way—an offer of collaboration or access to a data set—you can exploit it quickly.”

He adds:

Research shows that good ideas are more likely to spring into your head when it is fuzzy and relaxed, not when you

are focused and concentrating, with caffeine at its maximum dose. Another principle is that if you get away from

a problem for a bit—say by taking a vacation or spending a weekend with your family—the answer may come to you

easily when you return to work on the problem.

Finally, Hall becomes quite practical:

To sum up, the big danger for an economist at your career stage is to get involved in so many seemingly meritorious

activities on campus, at journals, in Washington, at conferences, writing textbooks, serving clients, and the like, that

your life becomes crowded and you feel hassled. Worst of all, you find yourself starved of time for creative research. When

this happens, take out a piece of paper and write down all of the activities that fill your work day and decide which ones

to cross off. This sounds like trite self-help book advice, but it works.

His whole article is here and is definitely worth a read. One thing I would say he misses: Hall is at Stanford, a top research university. Perhaps, universities below that hallowed standard are still quantity oriented as they cannot judge quality – journalism or the endless re-labeling of the same idea again and again might be mistaken for fundamental research and lead to a pay rise or internal status. You might still just ignore that and go with Hall’s advice.

The blog is definitely helping both Jeff and me stay fuzzy and relaxed, as you can tell from our posts. But I have to sign off now, go make a list and cross some other things off….

Fresh from their rout of the Democrats, the G.O.P. are promising to repeal President Obama’s healthcare reform. There are lots of things that can be improved in the law but there are also some features that will be popular with voters. To think about the risks of repeal, I find it useful to recall my favorite Rumsfeld quote:

“[A]s we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns — the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

In the minds on most voters, the healthcare law in an unknown unknown – most of its provisions have not gone into effect and non-experts (and even experts?) have not read the bill fully. There was never a really serious discussion of the law in the main stream media so citizens just know various buzz words (“death panels”). The huge uncertainty made the law unpopular with voters and it gave Republicans an electoral advantage.

If the Republicans clamor to repeal the law, the Democrats can point to he features of the law that will be popular with voters (no denial of coverage for pre-existing conditions, kids can stay on their parents’ policies till they are twenty six..). The law will go from being an unknown unknown into known unknown/known known territory. There is only upside for Democrats from this change – uncertainty-averse voters can’t have a worse impression of the healthcare reform than they already have. They are judging the unknown unknown in its worst possible light. The risk for Republicans is that if voters find some parts of the law appealing, their assessment actually improves and the Republicans’ electoral advantage diminishes. Better to keep the details hidden.

There is a “middle of the road” strategy – repeal unpopular bits and keep the popular ones. I’m not sure if this is really viable either. It forces a serious discussion of the law. For example, if Republicans try to repeal the requirement to buy insurance coverage, there will be some discussion of the subsidies offered and the costs of getting rid of the provision (some people will not buy insurance and then free-ride on emergency care pushing up costs for everyone else). Even if the discussion is a mess, it can’t be worse than the shallow discussion we sat through last year.

My guess is that the usual promise of tax cuts seems to dominate healthcare repeal as a strategy for Republicans.