You are currently browsing Sandeep Baliga’s articles.

When the Spanish government hiked sales tax on theater tickets this past summer, Quim Marcé thought his theater was doomed. With one in four local residents unemployed, Marcé knew that even a modest hike in ticket prices might leave the 300-seat Bescanó municipal theater empty.

“We said, ‘This is the end of our theater, and many others.’ But then the next morning, I thought, we’ve got to do something, so that we don’t pay this 21 percent, and we pay something more fair,” says Marcé in Spanish.

He looked out his window at farmland that surrounds this village, two hours north of Barcelona, and suddenly had an idea: Instead of selling tickets to his shows, he’d sell carrots.

“We sell one carrot, which costs 13 euros [$16] -– very expensive for a carrot. But then we give away admission to our shows for free,” he explains in Spanish. “So we end up paying 4 percent tax on the carrot, rather than 21 percent, which is the government’s new tax rate for theater tickets.”

Classified as a staple, carrots are taxed at a much lower rate and were spared new tax hikes that went into effect here on September 1.

I associate the Republican Party with competition. The Party promotes free market ideals – even in education where it promotes charter schools and vouchers so that traditional public schools will have to improve if they want to successfully compete for students.

So why doesn’t the Republican Party embrace these ideals of fully? Republicans won reelection to the House in large part thanks to uncompetitive redistricting.

This makes the GOP weaker in the long run because it protects out of touch politicians from competition and from reality. Gerrymandering means that Republican Representatives can be oblivious to long-term demographic changes that are reshaping the electorate while Democratic Representatives in safe “districts” must disproportionately confront them. The lack of competition makes the Republican Party weaker and less responsive to demographic change. Only watching Fox News probably isn’t helping either.

The ramifications of this uncompetitive behavior likely influenced the outcome of the Presidential race and made it harder for Romney to win. Mitt Romney embraced positions associated with the far right of the Republican Party in order to win the primary nomination. Many of his opponents who forced this shift in Romney’s positions were elected to the House from uncompetitive districts. Bachmann’s district is estimated to be 8% more “Republican” than the nation.

If the Republican Party wants its next generation of leaders to be able to win state and national elections, it should embrace competition and renounce gerrymandering. It should create House Congressional Districts that reflect demographic trends. It should want to elect Representatives who could have a real shot at winning a state or a national election, not just those who can win in a District where the competition (and reality) have been eliminated.

Something to revisit when the fiscal cliff negotiations make you mad.

From a city council vote in Kentucky:

Robert McDonald learned the hard way that every vote counts.

McDonald, who is known to most people as Bobby, finished in a dead heat Tuesday with Olivia Ballou for the sixth and final seat on the Walton City Council.

Each candidate captured 669 votes, but one ballot McDonald is sure would have gone his way was never cast. His wife, Katie, who works nights as a patient care assistant at Christ Hospital and is finishing nurse’s training at Gateway Community and Technical College, didn’t make it to the polls yesterday.

“If she had just been able to get in to vote, we wouldn’t be going through any of this,” McDonald said. “You never think it will come down to one vote, but I’m here to tell you that it does.”

McDonald, 27, said his wife did not want to talk about not voting.

“She feels bad enough,” McDonald said. “She worked extra hours, goes to school and we have three kids, so I don’t blame her. She woke up about ten minutes before the polls closed and asked if she should run up, but I told her I didn’t think one vote would matter.”

From The Wages of Wins Journal:

I’ve decided to lump speed together with all of these other (hypothesized) factors under the general heading of “Floor Stretch”. We’ll use it for an exercise in theoretical sports economics…Whatever it is that truly makes up “Floor Stretch”, it has to be sufficiently valuable that it offsets the lower raw productivity of the smaller players….

Floor Stretch, however, is really a relative function. Having 5 point guards on the floor only stretches the other team if they don’t also have 5 point guards playing. In this sense, what we really care about is the ratio of Floor Stretch between the two teams competing. Theoretically, the Floor Stretch ratio is what the raw productivity must be balanced against in order to determine the best mix of players. This, then, gets us into some classical Game Theory….

I’m too focussed on the election to digest fully. But I got this from Goolsbee’s Twitter feed today – he must be confident?

In a striking last-minute shift, the Romney campaign has decided to invest its most precious resource — the candidate’s time — in a serious play to win Pennsylvania.

Mr. Romney’s appearance here on Sunday could be a crafty political move to seriously undercut President Obama, or it could be a sign of desperation. Either way, his visit represents the biggest jolt yet in a state that was until recently largely ignored in the race for the White House.

Over the last several days, with polls showing Mr. Obama’s edge in the state narrowing, Republicans have sprung into action and forced the Democrats to spend resources here that could have gone toward more competitive battleground states.

In a previous post, I discussed why it might be profitable to move ad budgets to non-battleground states if battlegrounds are saturated with coverage. Basically, if you are strong in the battleground states, by spending money in a non-battleground state, you can divert your competitor’s resources there too and, if you are weak, you have to go there out of necessity. Hence, you cannot determine whether Romney has momentum or not from his ad spending strategy. But what about his travel strategy? A candidate’s time is scarce, unlike his billion dollar ad budget, so it must be rationed carefully. So, what can we infer from the fact that Romney is campaigning in PA on Sunday?

The New York Times Electoral Map is useful to think through various scenarios. Romney needs to win NC, FL and VA to have any chance of making it to the White House. Visiting and campaigning in those states is part of his defensive strategy – he has no option but to devote attention to them. As everyone is saying, OH is the key to the door of the White House.

What should Romney do if he knows the President has a significant lead in OH? There is no point campaigning even more in VA, NC or FL because even if he wins them, he cannot win the Presidency without some other states. He has to shift campaigning to some other states to make it to 269 electoral votes so the House can give him the Presidency. Then, it might seem he should shift his time to CO, IA, NH or WI. But to make it to 269, Romney would have to win WI, CO and one of the other two (according to my manipulation of the NYT map). This is a tall order. On the other hand, if he wins PA with one of these other four states, he is through. MN does not have enough electoral votes to counterbalance a loss of OH so the choice comes down to MI versus PA. If Romney is closer in PA than MI, that breaks the tie. So, to summarize, it makes more sense to campaign in PA and try to win one other state than to try to win WI, CO and one other.

What if Romney is ahead in OH? Then, he still needs one of CO, NH, IA or WI to win. Not focussing on those states and defending OH, VA etc. exclusively could cost him the Presidency. In this scenario, Romney does not have the luxury of the time to campaign in PA.

Hence, the Romney campaign’s focus on PA only really makes sense if they know President Obama is well ahead in OH. There is no Romentum.

UPDATE (11/3): From NBC,

On party ID

In these surveys, Democrats enjoy a nine-point party-identification advantage in Ohio and a two-point edge in Florida. Republicans have argued that a nine-point advantage is too large in this current political environment; it was eight points in the Buckeye State during Obama’s decisive 2008 victory.

If you cut that party ID advantage in half, Obama’s six-point lead in Ohio is reduced to three points.

I take Rationalization to be the act of having a theory before you approach data and then cherry-picking the data that fits your theory. This leads to Self-Deception (or maybe deception if you are doing the cherry-picking to trick other people).

In a possibly related comment, here is the Nov 6 projection from UnSkewed Polls:

What is the Democratic equivalent to UnSkewed Polls? I do not know. My guess is they would forecast same as 2008: Obama 365, McCain 173. Or would they add in AZ and TX because of the large Latino populations?

The Romney campaign is expanding ad buys beyond the battleground states. Is there a huge swell of enthusiasm so Romney is trying for a blowout or is it a bluff?

The traditional model of political advertizing is the Blotto game. Each candidate can divide up a budget across n states. Each candidate’s probability of winning at a location is increasing in his expenditure and decreasing in the other’s. These models are hard to solve for explicitly. What makes this election unusual is that the usual binding constraint – money – is slack in the battleground states. Instead, full employment of TV ad time and voter exhaustion with ads makes further expenditure unnecessary. But, you can still spend the money on improving your get-out-the-vote operation or to expand your ad buy to other states. Finally, you can send your candidate to a state. Your strategy varies as function of how close the race is.

If the battleground states are increasingly unlikely to be in your column, then a get out the vote strategy will not be enough to tip them back in your favor. Better to try to make some other state close by advertizing and mobilizing there. You must maintain your ad buy though in the battleground states to keep your competitor engaged so that they cannot divert resources themselves.

If the battleground states are close, then a get out the vote operation is quite useful even if ad spending is at its maximum. Better to do that than spend money in other locations where you are way behind.

If you are far ahead in the battleground states, you have to keep on spending there as your competitor is spending there either because he might win or to keep you spending there. But, cash you have sloshing around should be spent “expanding the map”. This gives you more paths to victory and also exerts a negative externality on your opponent, forcing him to divert resources including perhaps the most valuable resource of all, the candidate’s time.

So, you might spend heavily in a state even when you have little chance there. This always has the benefit of diverting your opponent’s attention. This means there is an incentive for a player to invest even if he is far ahead in the battleground states. But there is also an incentive to invest when you are behind as you need more paths to victory and expenditure on getting out the vote is less useful. So, we can’t infer Romentum from the fact that Romney is advertizing in MN and PA.

I think we can make stronger inferences by making a leap of faith and extrapolating this intuition to a state by state analysis. By comparing strategies with public polls, we can try to classify them into the three categories.

NC seems to fall into the first category for President Obama. Romney is ahead according to the polls but it gives the Obama campaign more ways to win and keeps the Romney resources stretched. Romney is roughly as far behind in MI, MN and PA as Obama is in NC. So, they play the same role for Romney as NC does for Obama. Bill Clinton and Joe Biden are campaigning in PA and MN so the Romney strategy has succeeded in diverting resources.

The most scarce resource is candidate time so we can infer a lot from the candidate recent travel and their travel plans. If the race is close in any states it would be crazy to try a diversion strategy as a candidate visit acts like a get out the vote strategy and hence has great benefits when the race is close. The President is campaigning in WI, FL, NV, VA and CO. In fact, both candidates are frequently in FL and VA. NC is a strong state for Romney because, as far as I can tell, he has no plans to visit there and nor does the President. Similarly, I don’t see any Romney pans to visit MI, MN or PA. Also, NV also seems to be out of Romney’s grasp as he has no plans to travel there. It is hard to make inferences about NH as Romney lives there so it is easy to campaign. OH has so many electoral votes that no candidate can afford not to campaign there – again no inferences can be made. Both candidates are in IA.

So, I think the state by state evidence is against Romentum. NC and NV do not seem to be in play. The rest of the battleground states are going to enjoy many candidate visits so they must be close. That’s about all I have!

Michael McDonald, a political science professor at George Mason University, constantly updates the numbers. In the early voting, NV, IA seem to be leaning Obama, CO is leaning Romney and FL is close. Hard to map OH counties into DEM and REP districts.

[L]ike millions of other people up and down the East Coast, we stocked up this weekend on peanut butter and crackers and powdered milk and bottled water and cans of beans and tomatoes and tuna. The prices for all those things were the same as they always are…

Even in states without price gouging laws, most stores won’t raise prices for generators or bottled water or canned food. Which raises a question: Why? Why doesn’t price go up when demand increases? Why don’t we see more price gouging?

The people Kahneman surveyed said they would punish businesses that raised prices in ways that seemed unfair. While I would have paid twice the normal price for my groceries yesterday, I would have felt like I was getting ripped off. After the storm passed, I might have started getting my groceries somewhere else.

Businesses know this. And, Kahneman argues, when basic economic theory conflicts with peoples’ perception of fairness, it’s in a firm’s long-term interest to behave in a way that people think is fair.

The reasoning of the store is an impeccable rational choice strategy: even if the store owner wants to make money in the short run, he forgoes the extra profit in the short run to make money in the long run. That is, even if he is not altruistic, he plays the same strategy as the altruist by refraining from price gouging. That leaves the consumer. In one version, suppose the consumer does not know if he is dealing with an altruistic store owner or a “rational” player. If the store price gouges, the consumers learns the store owner is not an altruist as an altruist would never price gouge. The consumer cares about the future, like the store owner. Since the store owner is rational, he may cheat the consumer sometime in the future. This could be because of end game effects when the store owner is desperate for cash or because he thinks he is has lost the consumer’s long run business so they have switched to a “bad” equilibrium of the repeated game. (This is standard repeated game reasoning in the style of Abreu-Pearce-Stacchetti or Fudenberg-Levine-Maskin or reputation reasoning in the style of Kreps-Milgrom-Roberts-Wilson.) So, the consumer rationally does not buy in the future from a store that price gouged him in the present not because of unfairness but because he will be cheated by the store owner. So the store and consumer strategies hang together as an equilibrium based on rational choice principles.

This narrative should be added to the storybook of rational choice analysis as well as behavioral economics alternatives.

A useful post by Peter Kellner at YouGov:

In all polls these days, the raw data must be handled with care. It’s normal for the sample to contain too many people in some groups, and too few in others. So all reputable pollsters adjust their raw data to remove these errors. It is standard practice to ensure that the published figures, after correcting these errors, contain the right number of people by age, gender, region and either social class (Britain) or highest educational qualification (US). Most US polls also weight by race.

Beyond that, there are two schools of thought. Should polls correct ONLY for these demographic factors, or should they also seek to ensure that their published figures are politically balanced? In Britain these days, most companies employ political weighting. YouGov anchors its polls in what our panel members told us at the last general election; other companies ask people in each poll how they voted in 2010, and use this information to adjust their raw data. Ipsos-MORI are unusual in NOT applying any political weighting.

Pew and ABC/Washington Post polls on the other hand does not control for party ID. Comparing election outcomes state by state on Nov 6 with election forecasts ay allow us to discriminate among these various philosophies.

“Goran Arnqvist from Uppsala University has been studying the seed beetle’s nightmarish penis for years, using it as a model for understanding the more general evolutionary pressures behind diverse animal genitals. In 2009, he and colleage Cosima Hotzy found that males with the longest spines fertilise the most eggs and father the most young. It wasn’t clear why. Maybe they help him to anchor himself to the female, or scrape out rival sperm. Or perhaps the fact that the spines actually puncture the female is important. Regardless, long spines seemed to give males the edge in their sperm competitions.

But Hotzy and Arnqvist had only found a correlation, by comparing the penises of male seed beetles from around the world. To really test their ideas, they wanted to deliberately change the length of the spikes to see what effect that would have.

They did that in two ways: they artificially bred males for several generations to have either longer or short spines; and they shaved them with a laser….Both techniques produced males with differently sized spines, but similarly sized bodies.

The duo found that males with the shorter spines were indeed less likely to successfully fertilise the females. They also found clues as to why the males benefit from their long spines.”

The bottom line is that Boston fears scared Republicans won’t vote and Chicago fears confident Democrats won’t vote. And so, in this final stretch, Boston wants Republicans confident and Chicago wants Democrats scared. Keep that in mind as you read the spin.

In an patent race, the firm that is just about to pass the point where it wins the race and gets a patent has an incentive to slack off a bit and coast to victory. The competitor who is almost toast has an incentive to slack off as he has little chance of winning. But if the race is close, all firms work hard.

Elections are similar except the campaigns have the information about whether the campaign is close or not and the voters exert the costly effort of voting. Campaigns have an incentive to lie to maximize turnout so the team that’s ahead pretends not to be far ahead and the team that’s behind pretends the race is very close. As Klein says, no-one can believe their spin and no information can be credibly transmitted.

If they really want to influence the election, the campaigns have to take a costly action to attain credibility. For example, they can release internal polling. This gives their statements credibility at the cost of giving their opponent their internal polling data.

Jon Stewart asks Austan Goolsbee:

What we need to do in this country is make it a softer cushion for failure. Because what they say is the job creators need more tax cuts and they need a bigger payoff on the risk that they take. … But what about the risk of, you’re afraid to leave your job and be an entrepreneur because that’s where your health insurance is? … Why aren’t we able to sell this idea that you don’t have to amplify the payoff of risk to gain success in this country, you need to soften the damage of risk?

I guess there are two effects. First, as Stewart says, insurance against failure, including in the form of health insurance disconnected from a salaried job, encourages more people to become entrepreneurs. This is the occupational choice component. Second, insurance against failure reduces the incentive to work hard. This is the usual trade-off between risk-sharing and incentives in the classical principal-agent moral hazard model. The two effects move in opposite directions so the net effect on welfare is ambiguous (assuming we want more people to be entrepreneurs which is not clear!). As far as I know, the empirical work on the trade off between risk sharing and incentives finds weak support for any tradeoff. It would be nice to have a model to think things through. I assume someone must have written such a model but not sure of the reference.

From the Atlantic channeling Rajiv Sethi and Justin Wolfers:

[T]his morning, something very weird happened on Intrade. Mitt Romney began the day trailing the president 60 to 40 (i.e.: his chance of winning was priced at 40%). Suddenly, Romney surged to 49%, and the president’s stock collapsed, despite no game-changing news in the press. The consensus on Twitter seemed to be that somebody tried to manipulate the market….

The total quantity of Romney stock traded between 9:57 and 10:03 was around $17,800. But that’s not the “cost” of this manipulation (if that’s what it was), because the buyer got stock in return. If we value that stock at 41 (rather than the higher price he paid), the net cost of this manipulation/error was about $1,250.

Meanwhile the UK bookies are giving Obama a 5 in 7 chance of winning. This gap between the UK berrint market and Intrade has existed for quite a while. Is some SuperPac spending money consistently to maintain the difference? The marginal benefit of more ads must by now be quite low. Maybe this is all that’s left to spend on.

Scott Adams writes on his blog:

[Obama] is putting an American citizen in jail for 10 years to life for operating medical marijuana dispensaries in California where it is legal under state law. And I assume the President – who has a well-documented history of extensive marijuana use in his youth – is clamping down on California dispensaries for political reasons, i.e. to get reelected. What other reason could there be?

One could argue that the President is just doing his job and enforcing existing Federal laws. That’s the opposite of what he said he would do before he was elected, but lying is obviously not a firing offense for politicians.

Personally, I’d prefer death to spending the final decades of my life in prison. So while President Obama didn’t technically kill a citizen, he is certainly ruining this fellow’s life, and his family’s lives, and the lives of countless other minor drug offenders. And he is doing it to advance his career. If that’s not a firing offense, what the hell is?

In a now annual event, economists at Kellogg and the NU Econ Dept have been polled for their forecasts of who will win the Econ Nobel Prize next Monday. Jeff and I forgot to vote for each other but the rest of the predictions are below (the full write up is on the Kellogg Expertly Wrapped blog):

The Thomson-Reuters citation based predictions are Steve Ross, Tony Atkinson and Angus Deaton, and Robert Shiller.

NU and Kellogg have a large group of IO specialists and theorists. There is also a rich tradition in innovative work in incentive theory – Myerson, Holmstrom and Milgrom were at Kellogg in my department and did some of their best work here in the early 1980s.

So, I am somewhat discounting the latter three candidates with one caveat below. Tirole is also a perennial favorite given the IO bias. While I think all these researchers will get this prize eventually, their age works against them – they are too young. they did seminal work at a time when Duran Duran ruled the airwaves or perhaps the Smiths in the case of Tirole. The Nobel Committee is still sorting out the time when ABBA was Number One and Bjorn Borg won Wimbledon. (Note Swedish influence on pop culture was high in the 1970s!)

Surely there is the odd foray into the 1980s when a field has been overlooked (e.g. Krugman for new trade theory). Mechanism design, incentives have won several times so this works against them. But one might argue Tirole is the Krugman of IO (or that Krugman is the Tirole of trade given that new trade theory used oligopoly models!).

So, that brings Tirole back in as a prediction.

The age factor also means Bob Wilson, an intellectual hero for all of us who do economic theory, is more likely than others on this list. Holmstrom and Milgrom (and Roth?) are his students and they were inspired by his tutelage and research agenda. He also worked with David Kreps. So, some prize organized around Wilson might be another possibility.

I am completely discounting the Thomson-Reuters predictions because (1) finance people can’t get the prize so soon after the financial crisis even if they do behavioral fiance like Shiller and (2) there was a recent Growth and Development Nobel Symposium and it is too soon to give a prize to Deaton or Atkinson after that – the Committee needs to think it over.

I personally think the prize will go to Econometrics because there hasn’t been one since Engel and Granger. I have no expertize in the field so I won’t hazard a guess.

Lee Crawfurd emails me about events in Sudan. North and South Sudan have agreed to a price at which the North will supply oil to the South. On his blog, Roving Bandit, Lee writes:

So – whilst this seems like a good deal for North Sudan in the short run and a good deal for South Sudan in the long run, my main concern is the hold-up problem. What is stopping North Sudan ripping up the agreement in 3 years, demanding a higher cut, and just confiscating oil (again).

In his email he adds:

As it turns out, the South’s strategy is to resume piping oil through the North, but also to simultaneously build a pipeline through Kenya, giving them an extra option.

The fact that the North can hold up later makes it less likely that the North and South will invest and trade in their relationship now. This makes both the North and South worse off. For this difficulty to be resolved, the North has to be able to commit not to exploit the South in the future. But the Kenyan pipeline gives them this commitment power to some extent: If the North threatens to raise prices, the South can go the Kenya route. This means the North will not raise prices in the future and that is good for trade and the welfare of both parties. Paraphrasing the wrods of the great philosopher Sting, “If Someone Does Not Trust You, Set Them Free“.

One issue is that the South may overinvest in the pipeline to get more bargaining power. That could lead to inefficiency as the North then has bad incentives.

Another classic Williamsonian solution is to use hostages to support exchange. I don’t know enough about North and South Sudan to know what they might transfer that is of little value to the recipient and high value to the donor. This sort of solution has been attempted recently in the US in the debt reduction negotiations. Automatic cuts in defense (bad for Republicans) and entitlement expenditures (bad for Democrats) go into force in January if Republicans and Democrats do not agree in debt negotiations. This has not worked so far. First, this is because there are crazy types who are willing to send the country over the “fiscal cliff”. Second, this is because there is no commitment and the automatic cuts can be delayed by Congress and so they are not real hostages.

My memory is terrible but I vaguely recall papers relating to investment in changing outside options in hold up models. These would be the most relevant to the Sudan scenario.

A great argument by Acemoglu and Robinson:

Another aspect is the divide between what the academic research in economics does — or is supposed to do — and the general commentary on economics in newspapers or in the blogosphere. When one writes a blog, a newspaper column or a general commentary on economic and policy matters, this often distills well-understood and broadly-accepted notions in economics and draws its implications for a particular topic. In original academic research (especially theoretical research), the point is not so much to apply already accepted notions in a slightly different context or draw their implications for recent policy debates, but to draw new parallels between apparently disparate topics or propositions, and potentially ask new questions in a way that changes some part of an academic debate. For this reason, simplified models that lead to “counterintuitive” (read unexpected) conclusions are particularly valuable; they sometimes make both the writer and the reader think about the problem in a total of different manner (of course the qualifier “sometimes” is important here; sometimes they just fall flat on their face). And because in this type of research the objective is not to construct a model that is faithful to reality but to develop ideas in the most transparent and simplest fashion; realism is not what we often strive for (this contrasts with other types of exercises, where one builds a model for quantitative exercise in which case capturing certain salient aspects of the problem at hand becomes particularly important). Though this is the bread and butter of academic economics, it is often missed by non-economists.

The Obama campaign claims that the Romney tax plan would result in an increase in taxes on the middle class, if you take it at its word that it would be revenue neutral. I took a look at an analysis done by the Tax Policy Center to get a more objective view. One of the authors, William Gale, worked in the CEA during the Bush I administration and another, Adam Looney, during the Obama administration. Their description of the Romney plan is:

This plan would extend the 2001-03 tax cuts, reduce individual income tax rates by 20 percent, eliminate taxation of investment income of most taxpayers (including individuals earning less than $100,000, and married couples earning less than $200,000), eliminate the estate tax, reduce the corporate income tax rate, and repeal the alternative minimum tax (AMT) and the high-income taxes enacted in 2010’s health-reform legislation.

Their preliminary conclusion:

We estimate that these components would reduce revenues by $456 billion in 2015 relative to a current policy baseline.

Therefore, over ten years this comes to 4.56 trillion. The Obama estimate seems to add in interest payments to round it out to 5 trillion dollars.

Since the Romney plan is meant to be revenue neutral where is this money coming from? First, some of it is recouped by eliminating various corporate tax breaks. Second, if the tax changes trigger greater growth this would generate tax revenue. Third it could come from closing other tax breaks on individuals. Once the TPC analysis accounts for the first two factors, they come up with a figure of $360 billion per annum of reduction in federal revenue from reducing income tax and eliminating the estate tax. This favors the rich. Even if deductions like mortgage interest tax deduction, tax free health insurance tax are adjusted or eliminated to raise revenue, this still leaves a hole of $86 billion/annum to be raised by increasing taxes on low and middle income taxpayers. The precise definition of middle class is a matter of debate. The TPC uses incomes below 200k and Marty Feldstein uses incomes below 100k and looks at 2009 data not a 2015 forecast like the TPC. There are other differences between the calculations but they are really not inconsistent: tax deductions would have to be eliminated to make up for the tax cuts. In Feldstein’s analysis, the burden falls on those with incomes between $100-200k.

The TPC does a robustness test on its growth estimates. If you use growth rates proposed by Romney advisor Greg Mankiw, federal revenue would fall by $307 billion still leaving $33 to be covered by people making less that $200k/annum.

But there are two points one can add which are implicit in the TPC analysis.

If you cut taxes but then eliminate deductions, there is no tax cut in aggregate – you give with one hand and take with the other. This means the impact on the work/leisure tradeoff is minimal, hence so is the impact on economic incentives and hence so is the impact on economic growth. Hence, the main impact of the Romney tax plan is distributional along the lines suggested by the TPC. A nice clear article from the American Enterprise Institute explains why reducing taxes while eliminating deductions does not have much effect on work incentives.

More dramatically, if the Romney plan gives with one hand and takes with the other, his whole economic plan collapses. It is founded on having tax cuts and triggering trickle down. But there is no real tax cut as deductions are eliminated at the same time taxes are cut. Hence, there is no Romney tax cut plan to stimulate growth.

Updates: Linked to TPC article and also an AEI article about revenue neutral tax policy.

The Romney campaign has been telegraphing that Mitt has been practicing zingers for the last two months. This brings to mind lessons from macro.

According to the Friedman/Lucas theory of monetary policy, money supply changes are only effective if they are unexpected. If they are expected, then nominal wages adjust to compensate for inflation so there is no change in the real wage and hence unemployment remains at the “natural rate” or the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU). But an unexpected increase in the money supply leads to surprise inflation, a decrease in the real wage and less unemployment. An unexpected decrease in the money supply leads to surprise deflation, an increase in the real wage and more unemployment. This is the expectations augmented Philips’ curve if I remember my macro correctly. And so it goes with zingers.

If Mitt’s zingers are unexpected, the audience responds with a better opinion of Mitt. If Mitt meets expectations, then there is no gain on net because there is no surprise. If he delivers fewer zingers than expected, then the audience is disappointed. (I believe Jeff, Emir Kamenica and Alex Frankel are working on a model of this sort of thing. Hopefully, the model can easily be extended to offer a theory of zingers.)

So, the campaign has deliberately set a high “natural rate” of zingers (NRZ) for Mitt. Then, Mitt definitely has to deliver zingers to meet the NRZ to avoid deflation and really he should deliver a huge amount so he exceeds NRZ. The Romney campaign should have downplayed zingers and Mitt’s NRZ, so their man is under less pressure. In fact, that is what the Obama team has been doing for their candidate.

There is the possibility that the Romney team was bluffing to scare the Obama team or to focus their attention on zinger defense rather than answers to real issues of jobs, foreign policy etc. But such a strategy is not costless because zingers are graded on an expectations augmented zinger curve.

A confusing article in the New York Times discusses a possible tomato trade war with Mexico. First, it says:

The United States Department of Commerce signaled then that it might be willing to end a 16-year-old agreement between the United States and some Mexican growers that has kept the price of Mexican tomatoes relatively low for American consumers. American tomato growers say the price has been so low that they can barely compete.

Later, the article adds more detail:

As part of a complex arrangement dating to 1996, the United States has established a minimum price at which Mexican tomatoes can enter the American market. Over the years, Florida’s tomato sales have dropped as low as $250 million annually, from as much as $500 million, according to Reggie Brown, executive vice president of the Florida Tomato Exchange, which has led the push to rescind the agreement. The state is the country’s largest producer of fresh market tomatoes, followed by California.

In the meantime, Bruno Ferrari, the economy minister of Mexico, said the value of Mexico’s tomato exports to the United States had more than tripled to $1.8 billion since the agreement was signed, and the tomato industry there supports 350,000 jobs.

Note the agreement established a MINIMUM price. If the agreement is dropped, then prices can go down further. In this interpretation, the agreement has not “kept the price of Mexican tomatoes relatively low for American consumers”. It has kept them high. This is probably good for Mexican farmers because it moves prices away from perfect competition and towards the monopoly price. It is also good for Florida producers who are competing with more expensive Mexican tomatoes. Obviously, it is bad for American consumers. Overall, we should expect both Mexican and Floridian (?) producers to oppose the end of this agreement.

If the agreement is being dropped to be replaced by free trade, it seems I will be buying cheaper tomatoes.

But, finally the article says:

The agreement, which has been amended since it was struck, sets the floor price for Mexican tomatoes at 17 cents a pound in the summer and 21.6 cents in the winter. American growers say they cannot compete at that price.

So, really what is on the cards is even higher minimum prices. This could still be good for Mexican growers as it should raise prices even more towards the monopoly price. But the problem is that more Florida farmers could then afford to grow and sell tomatoes. Then, the rationing rule that determines who makes the sale becomes important. If domestic growers are favored disproportionately, Mexican farmers will suffer. And I will be buying more expensive tomatoes or growing my own.

There should be some diagram that illustrates this so we can all use it in our Micro classes.

In his speech to the Clinton Global Initiative:

When I was in business, I traveled to many other countries. I was often struck by the vast difference in wealth among nations. True, some of that was due to geography. Rich countries often had natural resources like mineral deposits or ample waterways. But in some cases, all that separated a rich country from a poor one was a faint line on a map. Countries that were physically right next to each other were economically worlds apart. Just think of North and South Korea.

I became convinced that the crucial difference between these countries wasn’t geography. I noticed the most successful countries shared something in common. They were the freest. They protected the rights of the individual. They enforced the rule of law. And they encouraged free enterprise. They understood that economic freedom is the only force in history that has consistently lifted people out of poverty – and kept people out of poverty.

I guess someone on his staff read a synopsis of Acemoglu and Robinson.

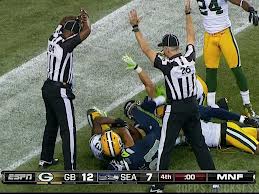

For the casual fan such as myself, the final second of the Packers-Seahawks game had the thrill of the Roman circus – an arbitrary, conflicted decision was handed down by emperor referees. For the real fans and the teams, it must be torture. But is it painful for the owners? After all, they will influence the decision in the labor dispute with referees. Steve Young thinks not:

The NFL is “inelastic for demand,” Young said, meaning that nothing — including poor officiating — can deter a significant percentage of fans and corporate sponsors away from the most popular game in the country. It’s the primary reason the NFL has held steady in its labor impasse with regular officials: There is no sign that enough of the sporting public cares to make it a priority.

“There is nothing they can do to hurt the demand of the game,” Young said in the video. “So the bottom line is they don’t care. Player safety doesn’t matter in this case. Bring Division III officials? Doesn’t matter. Because in the end you’re still going to watch the game.”

But the NFL/referee dispute is partly about “pay for performance” – the NFL wants to bench referees who botch calls (the money issues are trifling as a fraction of NFL revenue). This suggests the NFL does actually care about good officiating. This makes them weak in the face of the current officiating. They should cave sooner rather than later.

What Brown can’t do for you – if you are a Democrat – is give you control of the Senate. From the last Public Policy Polling analysis of MA:

Things have been going Elizabeth Warren’s way in the Massachusetts Senate race over the last month. She’s gained 7 points and now leads Scott Brown 48-46

after trailing him by a 49-44 margin on our last poll. Warren’s gaining because Democratic voters are coming back into the fold. Last month

she led only 73-20 with Democrats. Now she’s up 81-13. That explains basically the entire difference between the two polls. There are plenty of Democrats who like Scott Brown- 29% approve of him- but fewer are now willing to vote for him. That’s probably because of another finding on our poll- 53% of voters want Democrats to have control of the Senate compared to only 36% who want Republicans in charge. More and more Democrats who may like Brown are shifting to Warren because they don’t like the prospect of a GOP controlled Senate.

Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan have proposed a plan to allow private firms to compete with Medicare to provide healthcare to retirees. Beginning in 2023, all retirees would get a payment from the federal government to choose either Medicare or a private plan. The contribution would be set at the second lowest bid made by any approved plan.

Competition has brought us cheap high definition TVs, personal computers and other electronic goods but it won’t give us cheap healthcare. The healthcare market is complex because some individuals are more likely to require healthcare than others. The first point is that as firms target their plans to the healthy, competition is more likely to increase costs than lower them. David Cutler and Peter Orzag have made this argument. But there is a second point: the same factors that lead to higher healthcare costs also work against competition between Medicare and private plans. Unlike producers of HDTVs, private plans will not cut prices to attract more consumers so competition will not reduce the price of Medicare. A simple example exposes the logic of these two arguments.

Suppose there are two couples, Harry and Louise and Larry and Harriet. Harry and Louise have a healthy lifestyle and won’t need much healthcare but Larry and Harriet are unhealthy and are likely to require costly treatments in the future. Let’s say the Medicare price is $25,000/head as this gives Medicare “zero profits”. Harry and Louise incur much lower costs than this and Larry and Harriet much higher. Therefore, at the federal contribution, private plans make a profit if they insure Harry and Louise and a loss if they insure Larry and Harriet. So, private providers will insure the former and reject the latter. Or their plans deliberately exclude medical treatments that Larry and Harriet might need to discourage them from joining. The overall effect will be to increase healthcare costs. This is because Harry and Louise get premium support of $50,00 total that is greater than the healthcare costs they incur now so they impose higher costs on the federal government than they do currently. Larry and Harriet will be excluded by the private plans and will get coverage from Medicare. This will cost more than $50,000 total so there will be no cost savings from them either. Total costs will be higher than $100,00 as surplus is being handed over to Harry and Louise and their insurance companies.

To deal with this cream-skimming, we might regulate the marketplace. It might seem to make sense to require open enrollment to all private plans and stipulate that all plans at a minimum have the same benefits as the traditional Medicare plan. Indeed, the Romney/Ryan plan includes these two regulations. But this just creates a new problem.

Suppose the Medicare plan and all the private plans are being sold at the same price. The private plans target marketing at healthy individuals like Harry and Louise and include benefits such as “free” gym membership that are more likely to appeal to them. Hence, they still cream-skim to some extent and achieve a better selection of participants than the traditional public option. (This is actually the kind of thing that happens in the current Medicare Advantage system. Sarah Kliff has an article about it and Mark Duggan et al have an academic working paper studying Medicare Advantage in some detail.) So total healthcare costs will again be higher than in the traditional Medicare system.

But there is an additional effect. Traditional competitive analysis would predict that one private plan or another will undercut the other plans to get more sales and make more profits. This is the process that gives us cheap HDTVs. The hope is that similar price competition should reduce the costs of healthcare. Unfortunately, competition will not work in this way in the healthcare market because of adverse selection.

Going back to our story, if one plan is cheaper than the others priced at say $20,000, it will attract huge interest, both from healthy Harry and Louise but also from unhealthy Larry and Harriet. After all, by law, it must offer the same minimum basket of benefits as all the other plans. So everyone will want to choose the cheaper plan because they get same minimum benefits anyway. Also by law, the plan must accept everyone who applies including Larry and Harriet. So, while the cheapest plan will get lots of demand, it will attract unhealthy individuals whom the insurer would prefer to exclude – this is adverse selection. Insurers get a better shot at excluding Larry and Harriet if they keep their price high and dump them on Medicare. This means profits of private plans might actually be higher if the price is kept high and equal to the other plans and the business strategy focused on ensuring good selection rather than low prices. An HDTV producer doesn’t face any strange incentives like this– for them a sale is a sale and there is no threat of future costs from bad selection.

So, adverse selection prevents the kind of competition that lowers prices. The invisible hand of the market cannot reduce costs of provision by replacing the visible hand of the government.