You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘the web’ tag.

This is a very interesting article that has the unfortunate title “Plants Can Think And Remember.” (Unfortunate because the many links to it that I have seen come with snarky comments like “Whatcha gonna do now vegetarians??”)

It reminds me of a great joke: Three scientists are on the committee to decide mankind’s greatest invention. The engineer is arguing for the internal combustion engine, the doctor is arguing for the X-ray machine and Martha Stewart is arguing for the Thermos. “The Thermos, you’ve got to be kidding?” Sez Martha “Well you see it keeps hot things hot and cold things cold.” They look perplexed. “Yeah, big deal.” Martha: “How does it know??”

The article is about some pretty sophisticated ways that plants respond to signals in their environment. That is very cool. Kudos to the Plant Kingdom. But while, there may be something in the underlying research that justifies saying that plants “think”, I rather doubt it, and it is definitely not to be found in this journalistic account. Look:

In their experiment, the scientists showed that light shone on to one leaf caused the whole plant to respond.

“We shone the light only on the bottom of the plant and we observed changes in the upper part,” explained Professor Stanislaw Karpinski from the Warsaw University of Life Sciences in Poland, who led this research.

When I light a match to the coals at the bottom of my charcoal chimney, eventually all of them ignite and turn red even the ones on the top. My charcoal can think.

Then there’s stuff about “memory.” But I already knew that plants had memory. When I give my grass water today, it is green next week. When I don’t give my grass water today, it is brown next week. The grass changes its color next week depending on whether I give it water today. It remembers.

This is Asia:

It gets harder and harder to avoid learning the outcome of a sporting event before you are able to get home and watch it on your DVR. You have to stop surfing news web sites, stay away from Twitter, and be careful which blogs you read. Even then there is no guarantee. Last year I stopped to get a sandwich on the way home to watch a classic Roddick-Federer Wimbledon final (16-14 in the fifth set!) and some soccer-moms mercilessly tossed off a spoiler as an intermezzo between complaints about their nannys.

No matter how hard you try to avoid them, the really spectacular outcomes are going to find you. The thing is, once you notice that you realize that even the lack of a spoiler is a spoiler. If the news doesn’t get to you, then at the margin that makes it more likely that the outcome was not a surprise.

Right now I am watching Serena Williams vs Yet-Another-Anonymous-Eastern-European and YAAEE is up a break in the first set. But I am still almost certain that Serena Williams will win because if she didn’t I probably would have found out about it already.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. Unless the home team is playing, a big part of the interest in sports is the resolution of uncertainty. We value surprise. Moving my prior further in the direction of certainty has at least one benefit: In the event of an upset I am even more surprised. This has to be taken into account when I decide the optimal amount of effort to spend trying to avoid spoilers. It means that I should spend a little less effort than I would if I was ignoring this compensating effect.

It also tells me something about how to spend that effort. I once had a match spoiled by the Huffington Post. I never expected to see sports news there, but ex post I should have known that if HP is going to report anything about tennis it is going to be when there was an upset. You won’t see “Federer wins again” there.

Finally, if you really want to keep your prior and you recognize the effects above, then there is one way to generate a countervailing effect. Have your wife watch first and commit to a random disclosure policy. Whenever the favorite won, then with probability p she informs you and with probability 1-p she reveals nothing.

Heather Christle tweeted:

Pacifico beer tastes like it’s mad at me.

On the other hand, Elk Cove 2007 Wilamette Valley Pinot Noir tastes like it’s embarrassed by me. Almost as if we met once before on chatroullette and sensed immediately that we were bound by some primitive psychic traction and for the briefest instant we realized how all of history had in fact led us to this seemingly random moment, face to digitized face; only to be stopped, not more than an instant later by the simultaneous fear that our common epiphany could not be real but instead just a projection of our own deep sense of unfulfillment which now was out in the open plainly readable on our faces, the shame of which brought an end, by synchronized Nexting, to our only chance at untying life’s eternal knot, and as if now we have bumped into each other again at a party, introduced by mutual friends, and Elk Cove 2007 Wilamette Valley Pinot Noir glanced at its watch and escaped, avoiding eye contact and stammering about late hours and lost sleep.

While we are on the subject, you would be well-advised not to follow me on Twitter. Here is the link not to follow. Here are the kinds of things you are better off avoiding.

About a year ago I posted a link to a YouTube video of the Golden Balls “Split or Steal” game, hailing it as a godsend for teachers of game theory and the Prisoners’ Dilemma. That video has made its way around the web in the year since and I sat down to prepare my introductory game theory lecture yesterday looking for something new.

Well, it turns out that now there are many, many new videos of Split or Steal on YouTube and you can spend hours watching these. Here is my favorite and the one I used in class today.

I also heard from Seamus Coffey who has analyzed the data from Split or Steal games and finds:

- Women are more cooperative than men, non-whites more than whites, the old more cooperative than the young.

- There is more cooperation between opposite-sex players than when the players are of the same sex.

- The young don’t cooperate with the old, and the old discriminate even more against the young.

- Blonde women cooperate a lot. Men cooperate less with blondes than with brunettes.

Here is a link to a paper by John List who looks at similar patterns in the game Friend or Foe.

When you are competing to be the dominant platform, compatibility is an important strategic variable. Generally if you are the upstart you want your platform to be compatible with the established one. This lowers users’ costs of trying yours out. Then of course when you become established, you want to keep your platform incompatible with any upstart.

Apple made a bold move last week in its bid to solidify the iPhone/iPad as the platform for mobile applications. Apple sneaked into its iPhone OS Developer’s agreement a new rule which will keep any apps out of its App Store that were developed using cross-platform tools. That is, if you write an application in Adobe’s Flash (the dominant web-based application platform) and produce an iPhone version of that app using Adobe’s portability tools, the iPhone platform is closed to you. Instead you must develop your app natively using Apple’s software development tools. This self-imposed-incompatibility shows that Apple believes that the iPhone will be the dominant platform and developers will prefer to invest in specializing in the iPhone rather than be left out in the cold.

Many commentators, while observing its double-edged nature, nevertheless conclude that on net this will be good for end users. Jon Gruber writes

Cross-platform software toolkits have never — ever — produced top-notch native apps for Apple platforms…

[P]erhaps iPhone users will be missing out on good apps that would have been released if not for this rule, but won’t now. I don’t think iPhone OS users are going to miss the sort of apps these cross-platform toolkits produce, though. My opinion is that iPhone users will be well-served by this rule. The App Store is not lacking for quantity of titles.

And Steve Jobs concurs.

We’ve been there before, and intermediate layers between the platform and the developer ultimately produces sub-standard apps and hinders the progress of the platform.

Think about it this way. Suppose you are writing an app for your own use and, all things considered, you find it most convenient to write in a portable framework and export a version for your iPhone. That option has just been taken away from you. (By the way, this thought experiment is not so hypothetical. Did you know that you must ask Apple for permission to distribute to yourself software that you wrote?) You will respond in one of two ways. Either you will incur the additional cost and write it using native Apple tools, or you will just give up.

There is no doubt that you will be happier ex post with the final product if you choose the former. But you could have done that voluntarily before and so you are certainly worse off on net. Now the “market” as a whole is just you divided into your two separate parts, developer and user. Ex post all parties will be happy with the apps they get, but this gain is necessarily outweighed by the loss from the apps they don’t get.

Is there any good argument why this should not be considered anti-competitive?

With the help of DressRegistry.com:

Our goal is to lessen the chance that someone attending the same event as you will be wearing the EXACT same dress. We also hope we can be a resource for groups planning events through our message board and marketing partners. While it’s true we can not guarantee that someone else won’t appear in the same dress as you, the more that you (and others like you) use DressRegistry.com the lower that likelihood will be. So please use our site and have fun!

You find your event on their site and post a description and picture of the dress you will be wearing. When other guests check in to the site, they will know which dresses to avoid, in order to prevent dress disasters such as this one (Pink and Shakira, featured on the site):

The site promises “No personal information is displayed” but I wonder if anonymity is a desirable feature in this kind of mechanism. It seems to open the door to all kinds of manipulation:

- Chicken. Suppose you have your heart set on the Cache: green, ankle, strapless (picture here) but you discover that it has already been claimed for the North Carolina Museum of Art Opening Gala. You could put in a second claim for the same dress. You are playing Chicken and you hope your rival will back down. Anonymity means that if she doesn’t and the dress disaster happens, your safe because there’s only she-said she-said. Worried she might not back down? Register it 10 times.

- Hoarding. Not sure yet which dress is going to suit you on that day? Register everything that tickles your fancy, and decide later!

- Cornering the Market. You don’t just want to avoid dress disasters, you want to be the only one wearing your favorite color or your favorite designer or… Register away all the competition.

- Intimidation. Someone has already registered a knock-out dress that’s out of your price range. Register it again. She might think twice before wearing it.

If you are one of the millions of Facebook users who play games like Playfish or Pet Society, you are a datum in Kristian Segerstale’s behavioral economics experiments.

Instead of dealing only with historical data, in virtual worlds “you have the power to experiment in real time,” Segerstrale says. What happens to demand if you add a 5 percent tax to a product? What if you apply a 5 percent tax to one half of a group and a 7 percent tax to the other half? “You can conduct any experiment you want,” he says. “You might discover that women over 35 have a higher tolerance to a tax than males aged 15 to 20—stuff that’s just not possible to discover in the real world.”

Note that these are virtual goods that are sold through the game for (literal) money. And here is the website of the Virtual Economy Research Network which promotes academic research on virtual economies.

Because he is 17 year old Russian high-school student Andrey Ternovskiy. He’s the guy who created Chatroulette by himself, on a whim, in 3 months, and is now in the US fielding offers, meeting with investors, and considering never again returning to Moscow.

Should he sell? Would he sell? To frame these questions it is good to start by taking stock of the assets. He has his skills as a programmer, the codebase he has developed so far, and the domain name Chatroulette.com which is presently a meeting place for 30 million users with an additional 1 million new users per day. His skills, however formidable, are perfectly substitutable; and the codebase is trivially reproduceable. We can therefore consider the firm to be essentially equal to its unique exclusive asset: the domain name.

Who should own this asset? Who can make the most out of it? In a perfect world these would be distinct questions. Certainly there is some agent, call him G, which could do more with Chatroulete.com than Andrey, but in a perfect world, Andrey keeps ownership of the firm and just hires that person and his competitive wage.

But among the world’s many imperfections, the one that gets in the way here is the imperfection of contracting. How does Andrey specify G’s compensation? Since only G knows the best way to build on the asset, Andrey can’t simply write down a job description and pay G a wage. He’d have to ask G what that job description should be. And that means that a fixed wage won’t do. The only way to get G to do that special thing that will make Chatroulette the best it can be is to give G a share of the profits.

If Andrey is going to share ownership with G, who should have the largest stake? Whoever has a controlling stake in the firm will be the other’s employer. So, should G employ Andrey (as the chief programmer) or the other way around? Andrey’s job description is simple to write down in a contract. Whatever G says Chatroullete should do, Andrey programs that. Unlike when Andrey employs G, G doesn’t have to know how to program, he just has to know what the final product should do. And if Andrey can’t do it, G can just fire him and find someone who can.

So Andrey doesn’t need any stake in the profits to be incentivized to do his job, but G does. So G should own the firm completely and Andrey should be its employee. The asset is worth more with this ownership structure in place, so Andrey will be able to sell for a higher price than he could expect to earn if he were to keep it.

Jason Kottke tweeted:

Kids, don’t ever aspire to be the world’s oldest person. Have you not noticed that they’re always dying?

which is a good point but I would bet big money that the world’s youngest person dies more often than the oldest.

I don’t want an iPad because I don’t want to carry around a big device just to read. I want to read on my iPhone. With one hand. (Settle down now. I need the other hand to hold a glass of wine.) But the iPhone has a small screen. Sure I can zoom, but that requires finger gestures and also scrolling to pan around. Tradeoff? Maybe not so much:

Imagine a box. Laying on the bottom of the box is a piece of paper which you want to read. The box is closed, but there is an iPhone sized opening on the top of the box. So if you look through the opening you can see part of the paper. (There is light inside the box, don’t get picky on me here.)

Now imagine that you can slide the opening around the top of the box so that even if you can only see an iPhone sized subset of the paper, you could move that “window” around and see any part of the paper. You could start at the top left of the box and move left to right and then back to the left side and read.

Suppose you can raise and lower the lid of the box so you have two dimensions of control. You can zoom in and out, and you can pan the iPhone-sized-opening around.

Now, forget about the box. The iPhone has an accelerometer. It can sense when you move it around. With software it can perfectly simulate that experience. I can read anything on my iPhone with text as large as I wish, without scrolling, by just moving the phone around. With one hand.

This should be the main UI metaphor for the whole iPhone OS.

Chat Roulette (NSFA) is a textbook random search and matching process. Except that it is missing a key ingredient: an instrument for screening and signaling. That, coupled with free entry, means that everyone’s payoff is driven to zero.

In practice the big problems with Chat Roulette are

- Too many lemons

- Too much searching

- The incentive do something attention grabbing in the first few seconds is too strong

On the other, hand I expect the next generation of this kind of service to be a tremendous money maker. Here are some ideas to improve on it. The general idea is to create a mechanism where better partners are able to more easily find other good partners.

- Users maintain a score equal to the average length of their past chats. The idea is to give incentives to invest more in each chat, and to reward people who can keep their partners’ attention for longer. A user with a score of x is given the ability to restrict his matches to other users with a score greater than any z≤x he specifies. This is probably prone to manipulation by users who just keep their chats open inviting their partners to do the same and pad their numbers.

- Within the first few seconds of a match, each partner bids an amount of time they would like to commit to the current match. The system keeps the chat open for the smaller of the two numbers. Users maintain a score equal to the average amount of time other users have bid for them. Scores are used to restrict future matching partners just as above.

- Match users in groups of 10 instead of 2. Each member of the group clicks on one of the others and any mutually-clicking pair joins a chat. This could be coupled with a system like #1 above to mitigate the manipulation problem. Or your score could be the frequency with which others click on you.

- A simple “like/don’t like” rating system at the end of each chat. In order to make this incentive-compatible, you have an increased chance of meeting the same person again in future matches if both of you like each other. On top of that, your score is equal to the number of times people like you.

- Same as 4, but your score is computed using ranking algorithms like Google’s PageRank where it’s worth more to be liked by a well-liked partner.

- Multiple channels with their own independent scores. You could imagine that systems like the above would have multiple equilibria where the tastes of users with the highest scores dominate, thus reinforcing their high scores. Multiple channels would allow diversity by supporting different equilibria.

- Allow users to indicate gender preference of their matches. To avoid manipulation, your partners report your gender to the system.

These are all screening mechanisms: you earn control over whom you match with. But the system also needs a signaling mechanism: a way for a brand new user to signal to established users that she is worth matching with. The problem is that a good signal requires a commitment to lose reputation if you don’t measure up. But without a way to stop users from just creating new identities, these penalties have no force.

This is a super-interesting design problem and someone who comes up with a good one is going to get rich. (NB: Sandeep’s and my consulting fees remain quite modest.)

OKCupid is a dating site that has attracted attention by analyzing data from its users and publicizing interesting analyses on its blog. For example, a lot of traffic to their site came from this article on the profile photos that generated the most responses.

Mr. Yagan and three other Harvard mathematicians founded OkCupid in 2004. In its fight against much bigger competitors like Match.com, PlentyOfFish and eHarmony, it has tried a number of marketing techniques, often with little success. But the blog, which OkCupid started in October, has helped get the company’s name out on other blogs and social networks. A post last month that set out to debunk conventional wisdom about profile pictures brought more than 750,000 visitors to the site and garnered 10,000 new member sign-ups, according to the company.

But wouldn’t I worry that (my ideal mate would worry that her ideal mate would worry that…) the clientele this will appeal too is a tad too geek-heavy? (via Jacob Grier)

eBay combines a proxy bidding system with minimum bid increments. These interact in a peculiar way. If you have placed the first bid of $5 and the seller’s reserve is $1, then the initial bid is recorded at $1. Your true bid of $5 is kept secret and the system will bid for you (by “proxy”) until someone raises the price above $5.

Now I come along and bid, say $2. That’s not enough to outbid your $5, so you remain the high-bidder but the price is raised. In this case it is raised to $2 plus the minimum increment, say $0.50, provided that sum is less than your bid. In this case it is. But suppose the next bidder comes along and bids $4.75. Again you have not been outbid and so you remain the high bidder but in this case $4.75 + $0.50 is larger than $5, and when this happens the price is raised only to equal your bid, $5.

So, if you are bidding and your bid was not high enough to displace the high bidder but the price didn’t rise by the minimum increment above your bid, then the new price is exactly the (previously secret) bid of the high bidder. If you happen to also be the person selling the object up for sale and you are shill bidding, now is the time to stop because you have just raised the price to extract all of the surplus of the high bidder.

Notice how, as a shill bidder, you can incrementally bid the price up and, in most cases, hit but never overshoot the high bid. (“In most cases” because you must outbid the current price by the minimum increment and you get unlucky if the high bid falls in that gap. A good guess is that the high bidder is bidding in dollar denominations. If that is the case you can guarantee a perfect shill.)

This is discussed in a paper by Joseph Engelberg and Jared Williams (Kellogg PhDs.) The authors have a simple way to detect sellers who using shills in this way and they estimate that at least 1.3% of all bids are shill bids.

Homburg hail: barker.

Yahoo! has been building a social science group in their research division. In addition to some well-known economists, they have also been attracting ethnographers and cognitive psychologists away from posts at research universities.

The recruitment effort reflects a growing realization at Yahoo, the second most popular U.S. online site and search engine, that computer science alone can’t answer all the questions of the modern Web business. As the novelty of the Internet gives way, Yahoo and other 21st century media businesses are discovering they must understand what motivates humans to click and stick on certain features, ads and applications – and dismiss others out of hand.

However, there are risks when a for-profit company adopts an academic approach, which calls for publishing research regardless of the outcome. Notably, one set of figures from a study conducted by Reiley, the economist from the University of Arizona, raised eyebrows at Yahoo.…it could underscore a growing immunity to display advertising among the Web-savvy younger generation.The latter possibility would do little to bolster Yahoo’s sales pitch to advertisers hoping to influence this coveted age group. But raising such questions may be the cost of recruiting researchers committed to pure science.

When you search google you are presented with two kinds of links. Most of the links come from google’s webcrawlers and they are presented in an order that reflects google’s PageRank algorithm’s assessment of their likely relevance. Then there are the sponsored links. These are highlighted at the top of the main listing and also lined up on the right side of the page.

Sponsored links are paid advertisements. They are sold using an auction that determines which advertisers will have their links displayed and in what order. While the broad rules behind this auction are public, google handicaps the auction by adjusting bids submitted by advertisers according to what google calls Quality Score. (Yahoo does something similar.)

If your experience with sponsored links is similar to mine you might start to wonder whether Quality Score actually has the effect of favoring lower quality links. Renato Gomes, in his job market paper explains why this indeed might be a feature of the optimal keyword auction.

The idea is based on the well-known principle of handicaps for weak bidders in auctions. Let’s say google is auctioning links for the keyword “books” and the bidders are Amazon.com plus a bunch of fringe sites. If Amazon is willing to bid a lot for the ad but the others are willing to bid just a little, an auction with a level playing-field would allow Amazon to win at a low price. In these cases google can raise its auction revenues by giving a handicap to the little guys. Effectively google subsidizes their bids making them stronger competitors and thereby forcing Amazon to bid higher.

Of course its rare that the stronger bidder is so easy to identify and anyway the whole auction is run instantaneously by software. So how would google implement this idea in practice? Google collects data on how often users click through the (non-sponsored) links it provides to searchers. This gives google very good information about how much each web site benefits from link-generated traffic. That’s a pretty good, albeit imperfect, measure of an advertiser’s willingness to pay for sponsored links. And that’s all google would need to distinguish the strong bidders from the weak bidders in a keyword auction.

And when you put that all together you see that the weak guys will be exactly those websites that few people click through to. The useless links. The revenue-maximizing sponsored link auction favors the useless links and as a consequence they win the auction far more frequently than they would if the playing-field were level.

(To be perfectly clear, nobody outside of google knows exactly how Quality Score is actually calculated, so nobody knows for sure if google is intentionally doing this. The analysis just shows that these handicaps are a key part of a profit-maximizing auction.)

Renato’s job market paper derives a number of other interesting properties of an optimal auction in a two-sided platform. (Web search is a two-sided platform because the two sides of the market, users and advertisers, communicate through google’s platform.) For example, his theory explains why advertisers pay to advertise but users don’t pay to search. Indeed google subsidizes users by giving them all kinds of free stuff in order to thicken the market and extract more revenues from advertisers. On the other hand, dating sites, and some job-matching sites charge both sides of the market and Renato derives the conditions that determine which of these pricing structures is optimal.

- The top 20 internet lists of 2009. It starts off with a bang at #20: 5 cats that look like Wilford Brimley.

- A million lists of top-three books of 2009. I was not asked, but if I were asked I would have proven how literate and practical I am by listing Bolano’s 2666 even though I didn’t read it (and it was published in 2004.)

- Year-end list of lists about jazz in 2009. Coming in at #1 on the list of worst mustaches in the Bill McHenry Quintet… Bill McHenry!

- The Noughtie List. From Kottke.org. It’s got almost everything covered. One omission: I did not find the list of things not listed on that list.

Telephone is a kids’ game where the children sit in a circle and pass around a message by whispering in the neighbor’s ear. The game is to see how garbled the message gets by the time it makes it all the way around the circle. My 21st century version of telephone is played solitaire, using Google Translate.

- No, the only option at this point is to tackle her, landing you both deep in the snow

- (English -> French) Non, la seule option possible à ce point est à sa face, vous êtes tous deux d’atterrissage dans la neige

- (French -> Italian) No, l’unica opzione a questo punto è sul suo volto, si sono entrambi di atterraggio in mezzo alla neve

- (Italian -> Spanish) No, la única opción en este momento está en su cara, han de aterrizaje en la nieve

- (Spanish -> Chinese) 沒有,唯一的選擇在這個時候是你的臉,已經降落在雪地裡

- (Chinese -> Estonian) Ei, ainus võimalus sel ajal on oma nägu, on lossitud lumi

- (Estonian -> Afrikaans) Nee, die enigste opsie is op die oomblik is op jou gesig, dit geland in die sneeu

- (Afrikaans -> Turkish) Hayır, şu anda tek seçenek in your face, bu kar indi

- (Turkish -> English) No, currently the only option in your face, the snow fell

Hilarity ensues! (As usual, one of the kids seems to be sabatoging the game. Here we can see that it is the child translating from Afrikaans to Turkish.)

In this video, Steve Levitt and Stephen Dubner talk about their finding that you are 8 times more likely to die walking drunk than driving drunk.

Levitt says this

“anybody could have done it, it took us about 5 minutes on the internet trying to figure out what some of the statistics were… and yet no one has every talked or thought about it and I think that’s the power of ideas… ways of thinking about the world differently that we are trying to cultivate with our approach to economics.”

Dubner cites the various ways a person could die walking drunk

- step off the curb into traffic.

- mad dash across the highway.

- lie down and take a nap in the road.

Which leads him to see how obvious it is ex post that drunk walking is so much more dangerous than drunk driving.

I thought a little about this and it struck me that riding a bike while drunk should be even more dangerous than walking drunk. I could

- roll or ride off a curb into traffic.

- try to make a mad dash across an intersection.

- get off my bike so that i can lie down in the road to take a nap.

plus so many other dangerous things that i can do on my bike but could not do on foot. And what the hell, I have 5 minutes of time and the internet so I thought I would do a little homegrown freakonomics to test this out. Here is an excerpt from their book explaining how they calculated the risk of death by drunk walking.

Let’s look at some numbers, Each year, more than 1,000 drunk pedestrians die in traffic accidents. They step off sidewalks into city streets; they lie down to rest on country roads; they make mad dashes across busy highways. Compared with the total number of people killed in alcohol-related traffic accidents each year–about 13,000–the number of drunk pedestrians is relatively small. But when you’re choosing whether to walk or drive, the overall number isn’t what counts. Here’s the relevant question: on a per-mile basis, is it more dangerous to drive drunk or walk drunk?

The average American walks about a half-mile per day outside the home or workplace. There are some 237 million Americans sixteen and older; all told, that’s 43 billion miles walked each year by people of driving age. If we assume that 1 of every 140 of those miles are walked drunk–the same proportion of miles that are driven drunk–then 307 million miles are walked drunk each year.

Doing the math, you find that on a per-mile basis, a drunk walker is eight times more likely to get killed than a drunk driver.

I found the relevant statistics for cycling here, on the internet. I calculate as follows. Estimates range between 6 and 21 billion miles traveled by bike in a year. Lets call it 13 billion. If we assume that 1 out of every 140 of these miles are cycled drunk, then that gives about 92 million drunk-cycling miles. There are about 688 cycling related deaths per year (average for the years 200-2004.) Nearly 1/5 of these involve a drunk cyclist (this is for the year 1996, the only year the data mentions.) So that’s about 137 dead drunk cyclists per year.

When you do the math you find that there are about 1.5 deaths per every million miles cycled drunk. By contrast, Levitt and Dubner calculate about 3.3 deaths per every million miles walked drunk.

Is walking drunk more dangerous than biking drunk?

Here is another piece of data. Overall (drunk or not) the fatality rate (on a per-mile basis) is estimated to be between 3.4 and 11 times higher for cyclists than motorists. From Levitt and Dubner’s conclusion that drunk walking is 8 times more dangerous than drunk driving we can infer that there are about .4 deaths per million miles driven drunk. That means that the fatality rate for drunk cyclists is only about 3.8 times higher than for drunk motorists.

That is, the relative riskiness of biking versus driving is unaffected (or possibly attenuated) by being drunk. But while walking is much safer than driving overall, according to Levitt and Dubner’s method, being drunk reverses that and makes walking much more dangerous than both biking and driving.

There are a few other ways to interpret these data which do not require you to believe the implication in the previous paragraph.

- There was no good reason to extrapolate the drunk rate of 1 out of every 140 miles traveled from driving (where its documented) to walking and biking (where we are just making things up.)

- Someone who is drunk and chooses to walk is systematically different than someone who is drunk and chooses to drive. They are probably not going to and from the same places. They probably have different incomes and different occupations. Their level of intoxication is probably not the same. This means in particular that the fatality rate of drunk walkers is not the rate that would be faced by you and me if we were drunk and decided to walk instead of drive. To put it yet another way, it is not drunk walking that is dangerous. What is dangerous is having the characteristics that lead you to choose to walk drunk.

These ideas, especially the one behind #2 were the hallmark of Levitt’s academic work and even the work documented in Freakonomics. His reputation was built on carefully applying ideas like these to uncover exciting and surprising truths in data. But he didn’t apply these ideas to his study of drunk walking. Of course, my analysis is no better. I just copied some numbers off a page I found on the internet and applied the Levitt Dubner calculation. It only took me 5 minutes. (And I would appreciate if someone can check my math.) But then again, I am not trying to support a highly dubious and dangerous claim:

So as you leave your friend’s party, the decision should be clear: driving is safer than walking. (It would be even safer, obviously , to drink less, or to call a cab.) The next time you put away four glasses of wine at a party, maybe you’ll think through your decision a bit differently. Or, if you’re too far gone, maybe your friend will help sort things out. Because friends don’t let friends walk drunk.

Auction sites are popping up all over the place with new ideas about how to attract bidders with the appearance of huge bargains. The latest format I have discovered is the “lowest unique bid” auction. It works like this. A car is on the auction block. Bidders can submit as many bids as they wish ranging from one penny possibly to some upper bound, in penny increments. The bids are sealed until the auction is over. The winning bid is the lowest among all unique bids. That is, if you bid 2 cents and nobody else bids 2 cents, but more than one person bid 1 cent, then you win the car for 2 cents.

In some cases you pay for each bid but in some cases bids are free and you pay only if you win. Here is a site with free bidding. An iPod shuffle sold for $0.04. Here is a site where you pay to bid. The top item up for sale is a new house. In that auction you pay ~$7 per bid and you are not allowed to bid more than $2,000. A house for no more than $2,000, what a deal!

I suppose the principle here is that people are attracted by these extreme bargains and ignore the rest of the distribution. So you want to find a format which has a high frequency of low winning bids. On this dimesion the lowest unique bid seems even better than penny auctions.

Caubeen curl: Antonio Merlo.

Via kottke, Clusterflock gives five simple rules for effective bidding on eBay:

Step One:Find the product you want.

Step Two:

Save the product to your watch list.

Step Three:

Wait.

Step Four:

Just before the item ends, enter the maximum amount you are willing to pay for the item.

Step Five:

Click submit.

This is called sniping. That’s a pejorative label for what is actually a sensible and perfectly straightforward way to bid. eBay is essentially an open second-price auction and sniping is a way to submit a “sealed” bid. It’s a popular strategy and advocated by many eBay “experts.” But does it really pay off?

Tanjim Hossain and I did an experiment (ungated version.) We compared sniping to another straightforward strategy we call squatting. As the name suggests, squatting means bidding your value on an object at the very first opportunity, essentially staking a claim on that object. We bid on DVDs and randomly divided auctions into two groups, sniping on the auctions in the first group and squatting on the other.

The two strategies were almost indistinguishable in terms of their payoff. But for an interesting reason. A lot of eBay bidders use a strategy of incremental bidding. That’s where you act as if you are involved in an ascending auction (like an English auction) and you bid the minimum amount needed to become the high biddder. Once you are the high bidder you stop there and wait to see if you are outbid, then you raise your bid again. You do this until either you win or the price goes above the maximum amount you are willing to pay.

Against incremental bidders, sniping has a benefit and a cost (relative to squatting.) You benefit when incremental bidders stop at a price below their value. You swoop in at the end, the incremental bidders have no time to respond, and you win at the low price.

The cost has to do with competition across auctions for similar objects. If I squat on auction A and you are sniping in auction B, our opponents think there is one fewer competitor in auction B and more opponents enter auction B than A. This tends to raise the price in your auction relative to mine. In other words, squatting scares opponents away, sniping does not.

We found that these two effects almost exactly canceled each other out for auctions of DVDs. We expect that this would be true for similar objects that are homogeneous and sold in many simultaneous auctions. So the next time you are bidding in such an auction, don’t think too hard and just bid your value.

Now, I am still trying to figure out what I am going to do with all these copies of 50 First Dates we won in the experiment.

Tongue-in-cheek relationship advice from evolutionary psychology (via Mindhacks.)

Some Darwinists might say your optimal strategy would be to pair-bond with the older male but surreptitiously allow the younger, sexy male to fertilise you. But be careful, most men consider being cuckolded the greatest of betrayals.

And how about this?

You should have your husband medically assessed. It may be that some form of genetic disorder underlies his erratic behaviour, in which case he will need counselling and support. But you will also need to inform your daughters so that, if they are carriers, they do not themselves mate with men suffering from the same condition.

Big events at Northwestern this weekend, including Paul Milgrom’s Nemmers’ Prize lecture and a conference in his honor. (My relative status was microscopic.) A major theme of the conference was market design and I heard a story repeated a few times by participants connected with research and implementation of online ad auctions.

Ads served by Yahoo!, Google and others are sold to advertisers using auctions. These auctions are run at very high frequencies. Advertisers bid for space on specific pages at specific times and served to users which are carefully profiled by their search behavior. This enables advertisers to target users by location, revealed interests, and other characteristics.

Not content with these instruments, McDonalds is alleged to have proposed to Yahoo! a unique way to target their ads and their proposal has come to be known as The Happy Contract. Instead of linking their bids to personal profiles of users, they asked to link their bids to weather reports. McDonalds would bid for ad space only when and where the sun was shining. That way sunshine-induced good moods would be associated with impressions of Big Macs, and (here’s the winner’s curse) the foul-weather moods would get lumped with the Whopper.

I can relate to this.

For most of history, almost everything people did was forgotten because it was so hard to record and retrieve things. But this had a benefit: “social forgetting” allowed us to move on from embarrassing moments. Digital tools have eliminated this: Google caches copies of blog posts; networking sites thrive by archiving our daily dish. Society defaults to a relentless Proustian remembrance of all things past.

From an article in Wired.

I once linked to something like this. But that didnt hold a candle to this one:

Did you notice that when the song starts to go in the right direction his voice has an Eastern European accent? I have no idea whether this guy is a native English speaker. If he is then this is an artifact of singing backwards. If he really is Eastern European then it says something about language accents that they appear even when singing a foreign language backwards.

Its one of the many novel ideas from David K. Levine: the non-journal. You write your papers and you put them on your web site. Congratulations, you just published! Ah, but you want peer review. The editors of NAJ just might read your self-published paper and review it. We supply the peer-review, you supply the publication. Peer-review + publication = peer-reviewed publication. That was easy.

(NAJ is an acronym that stands for NAJ Ain’t a Journal.)

Its been around for a few years with pretty much the same set of editors. Its gone through some very active phases and some slow periods. David is trying to breathe some new life into NAJ by rotating in some new editors. So far so good. Arthur Robson is a new editor and he just reviewed a very cool paper by Emir Kamenica and Matthew Gentzkow called “Bayesian Persuasion.”

The paper tells you how a prosecutor manages to convict the innocent. Suppose that a judge will convict a defendant if he is more than 50% likely to be guilty and suppose that only 30% of all defendants brought to trial are actually guilty. A prosecutor can selectively search for evidence but cannot manufacture evidence and must disclose all the evidence he collects. The judge interprets the evidence as a fully rational Bayesian. What is the maximum conviction rate he can achieve?

The answer is 60%. This is accomplished with an investigation strategy that has two possible outcomes. One outcome is a conclusive signal that the defendant is innocent. Since the judge is Bayesian, the innocent signal occurs with probability zero when the defendant is actually guilty. The other outcome is a partially informative signal. If the prosecutor designs his investigation so that this signal occurs with probability 3/7 when the defendant is innocent (and with probability 1 when guilty) then

- conditional on this signal, the defendant is 50% likely to be guilty (we can make it strictly higher than 50% if you like by changing the numbers slightly)

- 3/7 of the innocent and all of the guilty will get this signal. (3/7 times 70%) + 30% = 60%.

The paper studies the optimal investigation scheme in a general model and uses it in a few applications.

Despite my vast legion of Twitter followers, every one of my attempts to start a new trending topic has failed to catch on. Now I think I understand why.

Suppose that your goal is to coordinate attention on a topic that seems to be on a lot of minds. Attention is a scarce resource and you have only a limited number of topics you can highlight. But suppose, as with Twitter, you see what everyone is talking about. How do you decide which topics to point to?

You probably shouldn’t just count the total number of people talking on a given subject, counting everyone equally. You might think that you would instead give extra weight to the few people that everyone is listening to. Because whatever they say is more likely to be interesting to many, and will soon be on many minds. On Twitter, those would be the people with the most followers. But there is a strong case for doing the opposite and giving extra weight to people with few followers, especially people who are relatively isolated in the social network. This is not out of fairness (or pity) but actually as the efficient way to use your scarce resource.

Efficient coordination means making information public so that not just everyone knows it, but everyone knows that everyone knows it (etc.) If we all have to choose simultaneously what to focus our attention on and we want to be part of the larger conversation, then it matters what we think others are going to focus their attention on. Coordinating attention thus requires making it public what people are talking about.

Suppose we have two topics that are getting a lot of attention, but topic A is being discussed by well-connected individuals and topic B is being discussed more by a diverse group of isolated individuals. Topic A is already public because when you see it discussed by a central figure you know that all other of her followers are seeing it to. Topic B therefore has more to gain from elevating it to the status of trending topic, which immediately makes it public.

I always knew that my Twitter followers were among the wisest. Now I see the true depth of their wisdom. By adding to my follower numbers, they reduce the weight of my comments in the optimal weighting scheme thus ensuring that the crazy things I say will be ingored by the larger network. Join the cause.

Swoopo.com has been called “the crack cocaine of auction sites.” Numerous bloggers have commented on its “penny auction” format wherein each successive bid has an immediate cost to the bidder (whether or not that bidder is the eventual winner) and also raises the final price by a penny. The anecdotal evidence is that, while sometimes auctions close at bargain prices, often the total cost to the winning bidder far exceeds the market price of the good up for sale. The usual diagnosis is that Swoopo bidders fall prey to sunk-cost fallacies: they keep bidding in a misguided attempt to recoup their (sunk) losses.

Do the high prices necessarily mean that penny auctions are a bad deal? And do the outcomes necessarily reveal that Swoopo bidders are irrational in some way? Toomas Hinnosaar has done an equilibrium analysis of penny auctions and related formats and he has shown that the huge volatility in prices is in fact implied by fully rational bidders who are not prone to any sunk-cost fallacy. In fact, it is precisely the sunk nature of swoopo bidding costs that leads a rational bidder to ignore them and to continue bidding if there remains a good chance of winning.

This effect is most dramatic in “free” auctions where the final price of the good is fixed (say at zero, why not?) Then bidding resembles a pure war of attrition: every bid costs a penny and whoever is the last standing gets the good for free. Losers go home with many fewer pennies. (By contrast to a war of attrition, you can sit on the sidelines as long as you want and jump in on the bidding at any time.) Toomas shows that when rational bidders bid according to equilibrium strategies in free auctions, the auction ends with positive probability at any point between zero bids and infinitely many bids.

So the volatility is exactly what you would expect from fully rational bidders. However, Toomas shows that there is a smoking gun in the data that shows that real-world swoopo bidders are not the fully rational players in his model. In any equilibrium, sellers cannot be making positive profits otherwise bidders are making losses on average. Rational bidders would not enter a competition which gives them losses on average.

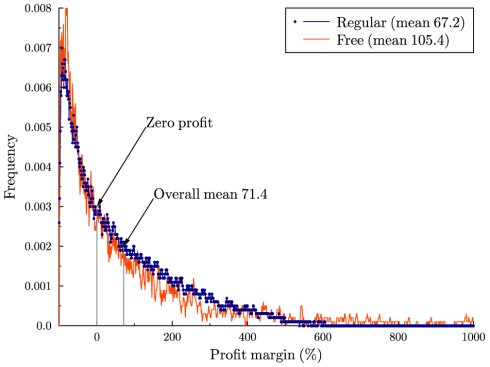

In the following graph you will see the actual distribution of seller profits from penny auctions and free auctions. The volatility matches the model very well but the average profit margin (as a percentage of the object’s value) is clearly positive in both cases. This could not happen in equilibrium.

Net neutrality refers to a range of principles ensuring non-discriminatory access to the internet. A particularly contentious principle urges prohibition of “managed” or “tiered” internet service wherein your internet service provider is permitted to restrict or degrade service. ISPs argue that without such permission they are unable to earn sufficient return on investment in network capacity and would be deterred from making such improvements.

One argument is based on congestion. Managed service controls congestion, raising the value to users and allowing providers to capture some of this value with access fees. This is a logical argument and one I will take up in a later post, but here I want to discuss another aspect of managed service: price discrimination.

Enabling providers to limit access, say by bandwidth caps, opens the door to “tiered” service where users can buy additional bandwidth at higher prices. This generally raises profits and so we should expect tiered service if net neutrality is abandoned. What effect does the ability to price discriminate have on an ISP’s incentive to invest in capacity?

It can easily reduce that incentive and this undermines the industry argument against net neutrality. Here is a simple example to illustrate why. Suppose there is a small subset of users who have a high willingness to pay for additional bandwidth. Under net neutrality, all users are charged the same price for access, and none have bandwidth restrictions. An ISP then has only two choices. Set a high price and sell only to the high-end users, or set a low price and sell to all users. When the high-end users are relatively few, profits are maximized with low prices and wide access. It is reasonable to think of this as describing the present situation.

Suppose tiered access is now allowed. This gives the ISP a new range of pricing schemes. The ISP can offer a low-price service plan with a bandwidth cap alongside a high-priced unrestricted plan. As we vary the cap associated with the low-end plan, we can move along a continuum from no cap at all to a 100% cap. These two extremes are equivalent to the two price systems available under net neutrality.

Often one of these in-between solutions will be more profitable than either of the two extremes. The reason is simple. The bandwidth cap makes the low-end plan less attractive to high-end users and as a result the ISP can raise the price of un-capped access to high-end users. It’s true that low-end users will pay less for capped service but often the trade-off is favorable to the ISP and total profits increase.

The upshot of this is that total bandwidth is lower, not higher, when an ISP unconstrained by net-neutrality uses the profit-maximizing tiered-service plan. Couched in the industry’s usual terms, the ISP’s incentive to increase network capacity is in fact reduced by moving away from net neutrality.

(Of course it can just as easily go the other way. For example, it may be that presently only the high-end users are being served because to lower price enough to attract the low end users, the ISP would lose too much profit from the high-end. In that case, allowing tiered service would induce the ISP to raise capacity and offer a capped service to previously excluded low-end users without significantly reducing profits from the high-end. Note however, this is not typically how industry lobbyists frame their argument.)

More

More