You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘game theory’ tag.

Bandwagon effects are hard to prove. If an artist is popular, does that popularity by itself draw others in? Are you more likely to enjoy a movie, restaurant, blog just because you know that lots of other people like it to? It’s usually impossible to distinguish that theory from the simpler hypothesis: the reason it was popular in the first place was that it was good and that’s why you are going to like it too.

Here’s an experiment that would isolate bandwagon effects. Look at the Facebook like button below this post. I could secretly randomly manipulate the number that appears on your screen and then correlate your propensity to “like” with the number that you have seen. The bandwagon hypothesis would be that the larger number of likes you see increases your likeitude.

An article in the journal Neuron documents an experiment in which monkeys were trained to play Rock Scissors Paper. When a monkey played a winning strategy he was likely to repeat it on the next round. When he played a losing strategy he was likely to choose on the next round the strategy that would have won on this round. The researchers were interested in how monkeys learn and they interpret the results as consistent with “regret”-based learning.

An article in the journal Neuron documents an experiment in which monkeys were trained to play Rock Scissors Paper. When a monkey played a winning strategy he was likely to repeat it on the next round. When he played a losing strategy he was likely to choose on the next round the strategy that would have won on this round. The researchers were interested in how monkeys learn and they interpret the results as consistent with “regret”-based learning.

Unfortunately in the experiment the monkeys were playing against a (minimax-randomizing) computer and not other monkeys. With this as a control it would now be interesting to see if they follow the same pattern when they play against another monkey. (With this pattern, the winning monkey would be negatively serially correlated.)

Vueltiao volley: Victor Shao.

Linkedin’s IPO followed the familiar pattern. Priced to initial investors at $45/share, the stock soared to a peak of $120/share on the first day of trading and closed at around $90. “Money was left on the table.” Felix Salmon has a good summary of different opinions about this and he briefly discusses auctions as an alternative to the traditional door-to-door IPO. You will recall that Google used an auction when it went public.

Like Mr. Salmon you might think that the winner’s curse would prevent an auction from discovering the right price and ensuring that money is not left on the table. The price-discovery properties of an auction rely on partially informed investors bidding according to their private information and this information thereby being reflected in the price. But a (potentially) winning bidder foresees that his win would mean that most other bidders bid less than he and that therefore “the market” is more pessmistic about the value of the firm than he is. Anticipating this, he underbids. Since all informed investors do this, the auction price will understate the value of the firm. Money will be left on the table again.

But an IPO is a multi-unit auction. Many shares are up for sale. A new strategic feature arises in these auctions, the loser’s curse. If you are outbid, then you know that many informed investors were more optimistic than you and this will make you regret having bid too low. This strategic force pushes you to raise your bid.

And in fact, as shown by Pesendorfer and Swinkels, for large auctions, under some quite general conditions, a uniform-price sealed bid auction produces a sales price which comes very close to the market’s best estimate of the value of the firm. No money is left on the table.

Via Mind Hacks, a story in the New York Times about twins conjoined at the head in such a way that they share brain matter and possibly consciousness.

Twins joined at the head — the medical term is craniopagus — are one in 2.5 million, of which only a fraction survive. The way the girls’ brains formed beneath the surface of their fused skulls, however, makes them beyond rare: their neural anatomy is unique, at least in the annals of recorded scientific literature. Their brain images reveal what looks like an attenuated line stretching between the two organs, a piece of anatomy their neurosurgeon, Douglas Cochrane of British Columbia Children’s Hospital, has called a thalamic bridge, because he believes it links the thalamus of one girl to the thalamus of her sister. The thalamus is a kind of switchboard, a two-lobed organ that filters most sensory input and has long been thought to be essential in the neural loops that create consciousness. Because the thalamus functions as a relay station, the girls’ doctors believe it is entirely possible that the sensory input that one girl receives could somehow cross that bridge into the brain of the other. One girl drinks, another girl feels it.

- The story is very interesting and moving. Worth a read.

- I would like to see them play Rock-Scissors-Paper.

- More generally, experimental game theory suffers from a mutliple-hypothesis problem. We assume rationality, and knowledge of the others’ strategy. Departures from theoretical predictions could come from violations of either of these two. The twins present a unique control.

Perfectionism seems like an irrational obsession. If you are already very close to perfect the marginal benefit from getting a little bit closer is smaller and smaller and, because we are talking about perfection, the marginal cost is getting higher and higher. An interior solution seems to be indicated.

But this is wrong. There is a discontinuity at perfection, a discrete jump up in status that can only be realized with literal perfection. Too see why, consider a competitive diver who performs his dive perfectly. Suppose that the skill of a diver ranges from 0 to 100, say uniformly distributed, and that only divers of skill greater than 80 can execute a perfect dive. Then conditional on a perfect dive, observers will estimate his skill to be 90. But if his dive falls short of perfection, no matter how close to perfection he gets, observers’ estimate of his skill will be bounded above by 80. That last step to perfection gives him a discontinuous jump upward in esteem.

Now of course in contests like diving, the competitors choose the difficulty of their dives. This unravels the drive to perfectionism because in fact the observers will figure out that he has chosen a dive that is easy enough for him to perfect. In equilibrium a diver of skill level q chooses a dive which can be perfected only by divers whose skill is q or larger. And then the choice of dive will perfectly reveal his skill. The discontinuity goes away.

But many activities have their level of difficulty given to us, and even among those where we can choose, most activities are not as transparent as diving. At a piano recital you hear only the pieces that the performers have prepared. You know nothing about the pieces they practiced but then shelved. The fame from pitching perfect game is not closely approximated by the notoriety of the near-perfect game.

You get to see only the blog post I wrote, not the ones that are still on the back burner.

(Drawing: Wait! from www.f1me.net)

How does the additional length of a 5 set match help the stronger player? Commenters to my previous post point out the direct way: it lowers the chance of a fluke in which the weaker player wins with a streak of luck. But there’s another way and it can in principle be identified in data.

To illustrate the idea, take an extreme example. Suppose that the stronger player, in addition to having a greater baseline probability of winning each set, also has the ability to raise his game to a higher level. Suppose that he can do this once in the match and (here’s the extreme part) it guarantees that he will win that set. Finally, suppose that the additional effort is costly so other things equal he would like to avoid it. When will he use his freebie?

Somewhat surprisingly, he will always wait until the last set to use it. For example, in a three set match, suppose he loses the first set. He can spend his freebie in the second set but then he has to win the third set. If he waits until the third set, his odds of winning the match are exactly the same. Either way he needs to win one set at the baseline odds.

The advantage of waiting until the third set is that this allows him to avoid spending the effort in a losing cause. If he uses his freebie in the second set, he will have wasted the effort if he loses the third set. Since the odds of winning are independent of when he spends his effort, it is unambiguously better to wait as long as possible.

This strategy has the following implications which would show up in data.

- In a five set match, the score after three sets will not be the same (statistically) as the score in a three set match.

- In particular, in a five-set match the stronger player has a lower chance of winning a third set when the match is tied 1-1 than he would in a three set match.

- The odds that a higher seeded player wins a fifth set is higher than the odds that he wins, say, the second set. (This may be hard to identify because, conditional on the match going to 5 sets, it may reveal that the stronger player is not having a good day.)

- If the baseline probability is close to 50-50, then a 5 set match can actually lower the probability that the stronger player wins, compared to a 3 set match.

This “freebie” example is extreme but the general theme would always be in effect if stronger players have a greater ability to raise their level of play. That ability is an option which can be more flexibly exercised in a longer match.

Andrew Caplin is visiting Northwestern this week to give a series of lectures on psychology and economics. Today he talked about some of his early work and briefly mentioned an intriguing paper that he wrote with Kfir Eliaz.

Too few people get themselves tested for HIV infection. Probably this is because the anxiety that would accompany the bad news overwhelms the incentive to get tested in the hopes of getting the good news (and also the benefit of acting on whatever news comes out.) For many people, if they have HIV they would much rather not know it.

How do you encourage testing when fear is the barrier? Caplin and Eliaz offer one surprisingly simple, yet surely controversial possibility: make the tests less informative. But not just any old way. Because we want to maintain the carrot of a positive result but minimize the deterrent of a negative result. Now we could try outright deception by certifying everyone who tests negative but give no information to those who test positive. But that won’t fool people for long. Anyone who is not certified will know he is positive and we are back to the anxiety deterrent.

But even when we are bound by the constraint that subjects will not be fooled there is a lot of freedom to manipulate the informativeness of the test. Here’s how to ramp down the deterrent effect of bad result without losing much of the incentive effects of a good result. A patient who is tested will receive one of two outcomes: a certification that he is negative or an inconclusive result. The key idea is that when the patient is negative the test will be designed to produce an inconclusive result with positive probability p. (This could be achieved by actually degrading the quality of the test or just withholding the result with positive probability.)

Now a patient who receives an inconclusive result won’t be fooled. He will become more pessimistic, that is inevitable. But only slightly more pessimistic. The larger we choose p (the key policy instrument) the less scary is an inconclusive result. And no matter what p is, a certification that the patient is HIV-negative is a 100% certification. There is a tradeoff that arises, of course, and that is that high p means that we get the good news less often. But it should be clear that some p, often strictly between 0 and 1, would be optimal in the sense of maximizing testing and minimizing infection.

In the New Yorker, Lawrence Wright discusses a meeting with Hamid Gul, the former head of the Pakistani secret service I.S.I. In his time as head, Gul channeled the bulk of American aid in a particular direction:

I asked Gul why, during the Afghan jihad, he had favored Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, one of the seven warlords who had been designated to receive American assistance in the fight against the Soviets. Hekmatyar was the most brutal member of the group, but, crucially, he was a Pashtun, like Gul.

But

Gul offered a more principled rationale for his choice: “I went to each of the seven, you see, and I asked them, ‘I know you are the strongest, but who is No. 2?’ ” He formed a tight, smug smile. “They all said Hekmatyar.”

Gul’s mechanism is something like the following: Each player is allowed to cast a vote for everyone but himself. The warlord who gets the most votes gets a disproportionate amount of U.S. aid.

By not allowing a warlord to vote for himself, Gul eliminates the warlord’s obvious incentive to push his own candidacy to extract U.S. aid. Such a mechanism would yield no information. With this strategy unavailable, each player must decide how to cast a vote for the others. Voting mechanisms have multiple equilibria but let us look at a “natural” one where a player conditions on the event that his vote is decisive (i.e. his vote can send the collective decision one way or the other). In this scenario, each player must decide how the allocation of U.S. aid to the player he votes for feeds back to him. Therefore, he will vote for the player who will use the money to take an action that most helps him, the voter. If fighting Soviets is such an action, he will vote for the strongest player. If instead he is worried that the money will be used to buy weapons and soldiers to attack other warlords, he will vote for the weakest warlord.

So, Gul’s mechanism does aggregate information in some circumstances even if, as Wright intimates, Gul is simply supporting a fellow Pashtun.

Here is a problem at has been in the back of my mind for a long time. What is the second best dominant-strategy mechanism (DSIC) in a market setting?

For some background, start with the bilateral trade problem of Myerson-Satterthwaite. We know that among all DSIC, budget-balanced mechanisms the most efficient is a fixed-price mechanism. That is, a price is fixed ex ante and the buyer and seller simply announce whether they are willing to trade at that price. Trade occurs if and only if both are willing and if so the buyer pays the fixed price to the seller. This is Hagerty and Rogerson.

Now suppose there are two buyers and two sellers. How would a fixed-price mechanism work? We fix a price p. Buyers announce their values and sellers announce their costs. We first see if there are any trades that can be made at the fixed price p. If both buyers have values above p and both sellers have values below then both units trade at price p. If two buyers have values above p and only one seller has value below p then one unit will be sold: the buyers will compete in a second-price auction and the seller will receive p (there will be a budget surplus here.) Similarly if the sellers are on the long side they will compete to sell with the buyer paying p and again a surplus.

A fixed-price mechanism is no longer optimal. The reason is that we can now use competition among buyers and sellers and “price discovery.” A simple mechanism (but not the optimal one) is a double auction. The buyers play a second-price auction between themselves, the sellers play a second-price reverse auction between themselves. The winner of the two auctions have won the right to trade. They will trade if and only if the second highest buyer value (which is what the winning buyer will pay) exceeds the second-lowest seller value (which is what the winning seller will receive.) This ensures that there will be no deficit. There might be a surplus, which would have to be burned.

This mechanism is DSIC and never runs a deficit. It is not optimal however because it only sells one unit. But it has the viture of allowing the “price” to adjust based on “supply and demand.” Still, there is no welfare ranking between this mechanism and a fixed-price mechanism because a fixed price mechanism will sometimes trade two units (if the price was chosen fortuitously) and sometimes trade no units (if the price turned out too high or low) even though the price discovery mechanism would have traded one.

But here is a mechanism that dominates both. It’s a hybrid of the two. We fix a price p and we interleave the rules of the fixed-price mechanism and the double auction in the following order

- First check if we can clear two trades at price p. If so, do it and we are done.

- If not, then check if we can sell one unit by the double auction rules. If so, do it and we are done.

- Finally, if no trades were executed using the previous two steps then return to the fixed-price and see if we can execute a single trade using it.

I believe this mechanism is DSIC (exercise for the reader, the order of execution is crucial!). It never runs a deficit and it generates more trade than either standalone mechanism: fixed-price or double auction.

Very interesting research question: is this a second-best mechanism? If not, what is? If so, how do you generalize it to markets with an arbitrary number of buyers and sellers?

Seth Godin writes:

When two sides are negotiating over something that spoils forever if it doesn’t get shipped, there’s a straightforward way to increase the value of a settlement. Think of it as the net present value of a stream of football…

Any Sunday the NFL doesn’t play, the money is gone forever. You can’t make up for it later by selling more football–that money is gone. The owners don’t get it, the players don’t get it, the networks don’t get it, no one gets it.

The solution: While the lockout/strike/dispute is going on, keep playing. And put all the profit/pay in an escrow account. Week after week, the billions and billions of dollars pile up. The owners see it, the players see it, no one gets it until there’s a deal.

There are two questions you have to ask if you are going to evaluate this idea. First, what would happen if you change the rules in this way? Second, would the parties actually agree to it?

Bargaining theory is one of the most unsettled areas of game theory, but there is one very general and very robust principle. What drives the parties to agreement is the threat of burning surplus. Any time a settlement proposal on the table it comes with the following interpretation: “if you don’t agree to this now you better expect to be able to negotiate for a significantly larger share on the next round because between now and then a big chunk of the pie is going to disappear.” Moreover it is only through the willingness to let the pie shrink that either party can prove that he is prepared to make big sacrifices in order to get that larger share.

So while the escrow idea ensures that there will be plenty of surplus once they reach agreement, it has the paradoxical effect of making agreement even more difficult to reach. In the extreme it makes the timing of the agreement completely irrelevant. What’s the point of even negotiating today when we can just wait until tomorrow?

But of course who cares when and even whether they eventually agree? All we really want is to see football right? And even if they never agree how to split the mounting surplus, this protocol keeps the players on the field. True, but that’s why we have to ask whether the parties would actually accept this bargaining game. After all if we just wanted to force the players to play we wouldn’t have to get all cute with the rules of negotiation, we could just have an act of Congress.

And now we see why proposals like this can never really help because they just push the bargaining problem one step earlier, essentially just changing the terms of the negotiation without affecting the underlying incentives. As of today each party is looking ahead expecting some eventual payoff and some total surplus wasted. Godin’s rules of negotiation would mean that no surplus is wasted so that each party could expect an even higher eventual payoff. But if it were possible to get the two parties to agree to that then for exactly the same reason under the old-fashioned bargaining process there would be a proposal for immediate agreement with the same division of the spoils on the table today and inked tomorrow.

Still it is interesting from a theoretical point of view. It would make for a great game theory problem set to consider how different rules for dividing the accumulated profits would change the bargaining strategies. The mantra would be “Ricardian Equivalence.”

Complaining about TSA screening is considered by the TSA to be cause for additional scrutiny.

Agent Jose Melendez-Perez told the 9/11 commission that Mohammed al-Qahtani “became visibly upset” and arrogantly pointed his finger in the agent’s face when asked why he did not have an airline ticket for a return flight.

But some experts say terrorists are much more likely to avoid confrontations with authorities, saying an al Qaeda training manual instructs members to blend in.

“I think the idea that they would try to draw attention to themselves by being arrogant at airport security, it fails the common sense test,” said CNN National Security Analyst Peter Bergen. “And it also fails what we know about their behaviors in the past.”

Analogous to “doctor shopping,” children practice parent shopping. My son comes to me and asks if he can play his computer game. When I say no, he goes and asks his mother. That is, assuming he hasn’t already asked her. After all how can I know that I’m not his second chance?

Indeed, if she is in another room and I have to make an immediate decision I should assume a certain positive probability that he has already approached her and she said no. Assuming that my wife had good reason to say no that inference alone gives me a stronger reason to say no than I already had. How much stronger?

If its an activity where he has learned from past experience that I am less willing to agree to, then for sure he asked his mother first and she said no. It’s no wonder I am the tough guy when it comes to those activities.

If its an activity where I am more lenient he’s going to come to me first for sure. But his strategic behavior still influences my answer. I know that if I say no, he’s going to her next and she’s going to reason exactly as in the previous paragraph. So she’s going to be tougher. Now sometimes I say no because I am really close to being on the fence and it makes sense to defer the decision to his Mother. Saying no effectively defers that decision because I know he’s going to ask her next. But now that his Mother is tougher than she would be in the first-best world, I must become a bit more lenient in these marginal cases.

Iterate.

(Addendum: If you want to know how to combat these ploys, go ask Josh Gans.)

Predict which flights will be overbooked, buy a ticket, trade it in for a more valuable voucher.

Still, there are some travelers who see the flight crunch as a lucrative opportunity. Among them is Ben Schlappig. The 20-year-old senior at the University of Florida said he earned “well over $10,000” in flight vouchers in the last three years by strategically booking flights that were likely to be oversold in the hopes of being bumped.

“I don’t remember the last time I paid over $100 for a ticket,” he boasted. His latest coup: picking up $800 in United flight vouchers after giving up his seat on two overbooked flights in a row on a trip from Los Angeles to San Francisco. Or as he calls it, “a double bump.”

The full article has a rundown of all the tricks you need to know to get into the bumpee business. I was surprised to read this.

Most of those people volunteered to give up their seats in return for some form of compensation, like a voucher for a free flight. But D.O.T. statistics also show that about 1.09 of every 10,000 passengers was bumped involuntarily.

On the other hand, it is not surprising because involuntary bumping only lowers the value of a ticket. Monetary (or voucher) compensation can be recouped in the price of the ticket (in expectation.)

Garrison grab: Daniel Garrett.

A former academic economist and game theorist is now the Chief Economic Advisor in the Ministry of Finance in India. His name is Kaushik Basu. Via MR, here is a policy paper he has just written advising that the giving of bribes should be de-criminalized.

The paper puts forward a small but novel idea of how we can cut down the incidence of bribery. There are different kinds of bribes and what this paper is concerned with are bribes that people often have to give to get what they are legally entitled to. I shall call these ―harassment bribes.‖ Suppose an income tax refund is held back from a taxpayer till he pays some cash to the officer. Suppose government allots subsidized land to a person but when the person goes to get her paperwork done and receive documents for this land, she is asked to pay a hefty bribe. These are all illustrations of harassment bribes. Harassment bribery is widespread in India and it plays a large role in breeding inefficiency and has a corrosive effect on civil society. The central message of this paper is that we should declare the act of giving a bribe in all such cases as legitimate activity. In other words the giver of a harassment bribe should have full immunity from any punitive action by the state.

This is not just crazy talk, there is some logic behind it fleshed out in the paper. If giving a bribe is forgiven but demanding a bribe remains a crime, then citizens forced to pay bribes for routine government services will have an incentive to report the bribe to the authorities. This will discourage harrassment bribery.

The obvious question is whether the bribe-enforcement authority will itself demand bribes. To whom does a citizen report having given a bribe to the bribe authority? At some point there is a highest bribe authority and it can demand bribes with impunity. With that power they can extract all of the reporter’s gains by demanding it as a bribe.

Worse still they can demand an additional bribe from the original harasser in return for exonerating her. The effect is that the harasser sees only a fraction of the return on her bribe demands. This induces her to ask for even higher bribes. Higher bribes means fewer citizens are able to pay them and fewer citizens receive their due government services.

The bottom line is that in an economy run on bribes you want to make the bribes as efficient as possible. That may mean encouraging them rather than discouraging them.

There are a few basic features that Grant Achatz and Nick Kokonas should build into their online ticket sales. First, you want a good system to generate the initial allocation of tickets for a given date, second you want an efficient system for re-allocating tickets as the date approaches. Finally, you want to balance revenue maximization against the good vibe that comes from getting a ticket at a non-exorbitatnt price.

- Just like with the usual reservation system, you would open up ticket sales for, say August 1, 3 months in advance on May 1. It is important that the mechanism be transparent, but at the same time understated so that the business of selling tickets doesn’t draw attention away from the main attractions: the restuarant and the bar. The simple solution is to use a sealed bid N+1st price auction. Anyone wishing to buy a ticket for August 1 submits a bid. Only the restaurant sees the bid. The top 100 bidders get tickets and they pay a price equal to the 101st highest bid. Each bidder is informed whether he won or not and the final price. With this mechanism it is a dominant strategy to bid your true maximal willingness to pay so the auction is transparent, and all of the action takes place behind the scenes so the auction won’t be a spectacle distracting from the overall reputation of the restaurant.

- Next probably wants to allow patrons to buy at lower prices than what an auction would yield. That makes people feel better about the restaurant than if it was always trying to extract every last drop of consumer’s surplus. Its easy to work that into the mechanism. Decide that 50 out of 100 seats will be sold to people at a fixed price and the remainder will be sold by auction. The 50 lucky people will be chosen randomly from all of those whose bid was at least the fixed price. The division between fixed-price and auction quantities could easily be adjusted over time, for different days of the week, etc.

- The most interesting design issue is to manage re-allocation of tickets. This is potentially a big deal for a restaurant like Next because many people will be coming from out of town to eat there. Last-minute changes of plans could mean that rapid re-allocation of tickets will have a big impact on efficiency. More generally, a resale market raises the value of a ticket because it turns the ticket into an option. This increases the amount people are willing to bid for it. So Next should design an online resale market that maximizes the efficiency of the allocation mechanism because those efficiency gains not only benefit the patrons but they also pay off in terms of initial ticket sales.

- But again you want to minimize the spectacle. You don’t want Craigslist. Here is a simple transparent system that is again discreet. After the original allocation of tickets by auction, anyone who wishes to purchase a ticket for August 1 submits their bid to the system. In addition, anyone currently holding a ticket for August 1 has the option of submitting a resale price to the system. These bids are all kept secret internally in the system. At any moment in which the second highest bid exceeds the second lowest resale price offered, a transaction occurs. In that transaction the highest bidder buys the ticket and pays the second-highest bid. The seller who offered the lowest price sells his ticket and receives the second lowest price.

- That pricing rule has two effects. First, it makes it a dominant strategy for buyers to submit bids equal to their true willingness to pay and for sellers to set their true reserve prices. Second, it ensures that Next earns a positive profit from every sale equal to the difference between the second-highest bid and the second-lowest resale price. In fact it can be shown that this is the system that maximizes the efficiency of the market subject to the constraint the market is transparent (i.e. dominant strategies) and that Next does not lose money from the resale market.

- The system can easily be fine-tuned to give Next an even larger cut of the transactions gains, but a basic lesson of this kind of market design is that Next should avoid any intervention of that sort. Any profits earned through brokering resale only reduces the efficiency of the resale market. If Next is taking a cut then a trade will only occur if the gains outweigh Next’s cut. Fewer trades means a less efficient resale market and that means that a ticket is a less flexible asset. The final result is that whatever profits are being squeezed out of the resale market are offset by reduced revenues from the original ticket auction.

- The one exception to the latter point is the people who managed to buy at the fixed price. If the goal was to give those people the gift of being able to eat at Next for an affordable price and not to give them the gift of being able to resell to high rollers, then you would offer them only the option to sell back their ticket at the original price (with Next either selling it again at the fixed price or at the auction price, pocketing the spread.) This removes the incentive for “scalpers” to flood the ticket queue, something that is likely to be a big problem for the system currently being used.

- A huge benefit of a system like this is that it makes maximal use of information about patrons’ willingness to pay and with minimal effort. Compare this to a system where Next tries to gauge buyer demand over time and set the market clearing price. First of all, setting prices is guesswork. An auction figures out the price for you. Second, when you set prices you learn very little about demand. You learn only that so many people were willing to pay more than the price. You never find out how much more than that price people would have been willing to pay. A sealed bid auction immediately gives you data on everybody’s willingness to pay. And at every moment in time. That’s very valuable information.

I am always writing about athletics from the strategic point of view: focusing on the tradeoffs. One tradeoff in sports that lends itself to strategic analysis is effort vs performance. When do you spend the effort to raise your level of play and rise to the occasion?

My posts on those subjects attract a lot of skeptics. They doubt that professional athletes do anything less than giving 100% effort. And if they are always giving 100% effort, then the outcome of a contest is just determined by gourd-given talent and random factors. Game theory would have nothing to say.

We can settle this debate. I can think of a number of smoking guns to be found in data that would prove that, even at the highest levels, athletes vary their level of performance to conserve effort; sometimes trying hard and sometimes trying less hard.

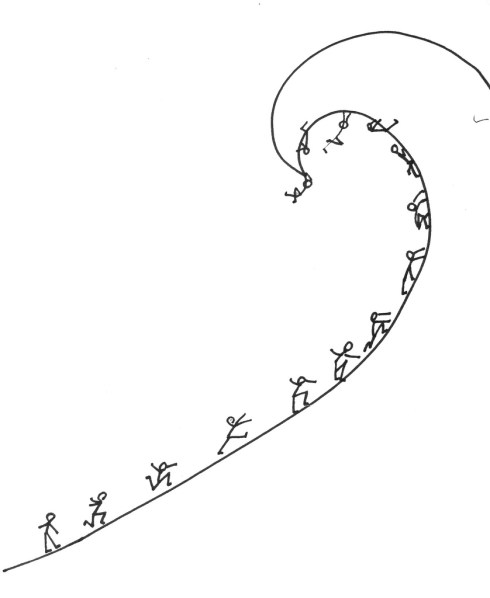

Here is a simple model that would generate empirical predictions. Its a model of a race. The contestants continuously adjust how much effort to spend to run, swim, bike, etc. to the finish line. They want to maximize their chance of winning the race, but they also want to spend as little effort as necessary. So far, straightforward. But here is the key ingredient in the model: the contestants are looking forward when they race.

What that means is at any moment in the race, the strategic situation is different for the guy who is currently leading compared to the trailers. The trailer can see how much ground he needs to make up but the leader can’t see the size of his lead.

If my skeptics are right and the racers are always exerting maximal effort, then there will be no systematic difference in a given racer’s time when he is in the lead versus when he is trailing. Any differences would be due only to random factors like the racing conditions, what he had for breakfast that day, etc.

But if racers are trading off effort and performance, then we would have some simple implications that, if it were born out in data, would reject the skeptics’ hypothesis. The most basic prediction follows from the fact that the trailer will adjust his effort according to the information he has that the leader does not have. The trailer will speed up when he is close and he will slack off when he has no chance.

In terms of data the simplest implication is that the variance of times for a racer when he is trailing will be greater than when he is in the lead. And more sophisticated predictions would follow. For example the speed of a trailer would vary systematically with the size of the gap while the speed of a leader would not.

The results from time trials (isolated performance where the only thing that matters is time) would be different from results in head-to-head competitions. The results in sequenced competitions, like downhill skiing, would vary depending on whether the racer went first (in ignorance of the times to beat) or last.

And here’s my favorite: swimming races are unique because there is a brief moment when the leader gets to see the competition: at the turn. This would mean that there would be a systematic difference in effort spent on the return lap compared to the first lap, and this would vary depending on whether the swimmer is leading or trailing and with the size of the lead.

And all of that would be different for freestyle races compared to backstroke (where the leader can see behind him.)

Finally, it might even be possible to formulate a structural model of an effort/performance race and estimate it with data. (I am still on a quest to find an empirically oriented co-author who will take my ideas seriously enough to partner with me on a project like this.)

Drawing: Because Its There from www.f1me.net

Republicans and Democrats are negotiating a budget deal in an effort to avert a government shutdown. The last time the government was forced to furlough workers, Congressional Republicans and their leader Newt Gingrich took much of the blame in the eyes of the public. It is generally believed that Republicans, the anti-goverment party, would again be blamed for a government shutdown should an agreement not be reached this time around.

The first-order analysis bears this out. While a government shutdown would be a bad outcome for all parties, it is relatively less bad for the anti-big-government Republicans. Other things equal you would infer that if a shutdown were not averted it would have been because the Republicans were willing to let that happen.

Of course other things are not equal. The second-order analysis is that Democrats, understanding that Republicans would take the blame now become relatively more willing to allow a shutdown. This affects the bargaining. Democrats are now emboldened to make more aggressive demands for two reasons. First, the cost of having their demands rejected is lower because they score political points in the event of a shutdown. Second, for that same reason Republicans are now more likely to accept an aggressive offer.

Will the blame equilibrate? Does the public internalize the second-order analysis and adjust its blame attribution accordingly? And what does equilibrium blame look like? Must it be applied equally to both parties?

In politics only the most transparent arguments hold sway with the public. The second-order analysis is too subtle to be used as a talking point even though probably everybody understands it perfectly well. A talking point is effective as long as it’s believed that many people believe it, even if in fact most people see right through it. So the first-order analysis will rule and the blame will not equilibrate.

In the current environment that could raise the chances of a government shutdown. Ideally Democrats would maximize their advantage by increasing their demands and stopping just short of the point where Republicans would rather trigger a shutdown. But the Tea Party complicates things. They might be so steadfast in their principles that they are not deterred by the blame. That could mean that the best deal Democrats can expect to reach agreement on is dominated by making a demand that the Tea Party rejects and forcing a shutdown.

In the last of our weekly readings, my daughter’s 4th grade class read Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Pit And The Pendulum” (a two minute read) and today I led the kids in a discussion of the story. Here are my notes.

The story reads like a scholarly thesis on the art and strategy of torture. My fourth graders had no trouble picking out the themes of commitment, credibility, resistance, and escalation as if they themselves were seasoned experts on the age-old institution. We went around the table associating passages in the story to everyday scenes on the playground and in the lunch line. Many of the children especially identified with this account of the delicate balance between hope and despair in the victim:

And then there stole into my fancy, like a rich musical note, the thought of what sweet rest there must be in the grave. The thought came gently and stealthily, and it seemed long before it attained full appreciation; but just as my spirit came at length properly to feel and entertain it, the figures of the judges vanished, as if magically, from before me; the tall candles sank into nothingness; their flames went out utterly; the blackness of darkness supervened; all sensations appeared swallowed up in a mad rushing descent as of the soul into Hades.

We had a lengthy discussion of how the victim was made to wish for death and one especially precocious youngster observed that the longing for death cultivates in the detainee what is known as the Stockholm Syndrome in which the victim begins to feel a sense of common purpose with his captors.

By long suffering my nerves had been unstrung, until I trembled at the sound of my own voice, and had become in every respect a fitting subject for the species of torture which awaited me.

Here Poe gives a nod to the eternal debate about the psychology of torture. Does psychological stress of torture bring the victim to a state in which he abandons all rationality? There in the hush of the elementary school library, the children were insistent that Poe was right to suggest instead that torture, judiciously applied, only heightens the victim’s strategic awareness.

In light of that observation it came as no surprise to the sharpest among my students that the instrument to be used would leverage to the fullest the interrogators’ strategic advantage in this contest of wills.

It might have been half an hour, perhaps even an hour, (for in cast my I could take but imperfect note of time) before I again cast my eyes upward. What I then saw confounded and amazed me. The sweep of the pendulum had increased in extent by nearly a yard. As a natural consequence, its velocity was also much greater. But what mainly disturbed me was the idea that had perceptibly descended. I now observed — with what horror it is needless to say — that its nether extremity was formed of a crescent of glittering steel, about a foot in length from horn to horn; the horns upward, and the under edge evidently as keen as that of a razor. Like a razor also, it seemed massy and heavy, tapering from the edge into a solid and broad structure above. It was appended to a weighty rod of brass, and the whole hissed as it swung through the air.

Still we were, every one of us, in awe of Poe’s ingenious device. The pendulum, serving both as a symbol of the deterministic and inexorable march of time, and a literal instrument of torture inheriting that same aura of inevitability.

I asked the youngest of my students, a gentle and charming, if somewhat reserved little girl to take her reader out of her Hello Kitty book bag and read aloud this entry, which I had highlighted as one whose vibrant color and imagery was sure to endear the students at such an early age to the rich joys of literature.

What boots it to tell of the long, long hours of horror more than mortal, during which I counted the rushing vibrations of the steel! Inch by inch — line by line — with a descent only appreciable at intervals that seemed ages — down and still down it came! Days passed — it might have been that many days passed — ere it swept so closely over me as to fan me with its acrid breath. The odor of the sharp steel forced itself into my nostrils. I prayed — I wearied heaven with my prayer for its more speedy descent.

This was the moment of my greatest pride in our weekly literary expeditions as I could tell that the child so was overcome with the joy and power of Poe’s insights into the art of interrogation, that she was nearly weeping at the end.

The story concludes with Poe’s most hopeful verdict on the limits of torture as a mechanism. Our victim persevered, resisted to the very end, and his steadfastness was rewarded with escape and rescue. Likewise, the little boys and girls went back to their classroom and I detected that they were moving unusually slowly. I surmised, I must say with a little pride, that they were still deep in thought about the valuable lesson we had explored together. Indeed many of them confided in me that they were eager to tell their parents about me and the story I picked for them and everything they learned today.

Suppose I want you to believe something and after hearing what I say you can, at some cost, check whether I am telling the truth. When will you take my word for it and when will you investigate?

If you believe that I am someone who always tells the truth you will never spend the cost to verify. But then I will always lie (whenever necessary.) So you must assign some minimal probability to the event that I am a liar in order to have an incentive to investigate and keep me in check.

Now suppose I have different ways to frame my arguments. I can use plain language or I can cloak them in the appearance of credibility by using sophisticated jargon. If you lend credibility to jargon that sounds smart, then other things equal you have less incentive to spend the effort to verify what I say. That means that jargon-laden statements must be even more likely to be lies in order to restore the balance.

(Hence, statistics come after “damned lies” in the hierarchy.)

Finally, suppose that I am talking to the masses. Any one of you can privately verify my arguments. But now you have a second, less perfect way of checking. If you look around and see that a lot of other people believe me, then my statements are more credible. That’s because if other people are checking me and many of them demonstrate with their allegiance that they believe me, it reveals that my statements checked out with those that investigated.

Other things equal, this makes my statements more credible to you ex ante and lowers your incentives to do the investigating. But that’s true of everyone so there will be a lot of free-riding and too little investigating. Statements made to the masses must be even more likely to be lies to overcome that effect.

Drawing: Management Style II: See What Sticks from www.f1me.net

This is an easy one: North Korea thinks (1) the US is out to exploit and steal resources from other countries and hence (2) Libya was foolish to giving away its main weapon, its nascent nuclear arsenal, which acted as a deterrent to American ambition. Accordingly,

“The truth that one should have power to defend peace has been confirmed once again,” the [North Korean] spokesperson was quoted as saying, as he accused the U.S. of having removed nuclear arms capabilities from Libya through negotiations as a precursor to invasion.

“The Libyan crisis is teaching the international community a grave lesson,” the spokesperson was quoted as saying, heaping praise on North Korea’s songun, or military-first, policy.

In a perceptive analysis, Professor Ruediger Franks adds two more examples that inform North Korean doctrine. Gorbachev’s attempts to modernize the Soviet Union led to its collapse and the emancipation of its satellite states. Saddam’s agreement to allow a no-fly zone after Gulf War I led inexorably to Gulf War II and his demise. The lesson: Get more nuclear arms and do not accede to any US demands.

Is there a solution that eliminates nuclear proliferation? Such a solution would have to convince North Korea that their real and perceived enemies are no more likely to attack even if they know North Korea does not have a nuclear deterrent. Most importantly, the US would have to eliminate North Korean fear of American aggression. In a hypothetical future where the North Korean regime has given up its nuclear arsenal, suppose the poor, half-starved citizens of North Korea stage a strike and mini-revolt for food and shelter and the regime strikes back with violence. Can it be guaranteed that South Korea does not get involved? Can it be guaranteed that Samantha Power does not urge intervention to President Obama in his second term or Bill Kristol to President Romney in his first? No. So, we are stuck with nuclear proliferation by North Korea. The only question is whether North Korea can feel secure with a small arsenal.

Tomas Sjostrom and I offer one option for reducing proliferation in our JPE paper Strategic Ambiguity and Arms Proliferation. If North Korea can keep the size and maturity of its nuclear arsenal hidden, we can but guess at its size and power. It might be large or quite small – who knows. This means even if the arsenal is actually small, North Korea can still pretend it is big and get some of the deterrent power of a large arsenal without actually having it. The potential to bluff afforded by ambiguity of the size of weapons stockpiles affords strategic power to North Korea. It reduces North Korea’s incentive to proliferate. And this in turn can help the U.S. particularly if they do not really want to attack North Korea but fear nuclear proliferation. Unlike poker and workplace posturing à la Dilbert, nuclear proliferation is not a zero-sum game. Giving an opponent the room to bluff can actually create a feedback loop that helps other players.

Almost every kind of race works like this: we agree on a distance and we see who can complete that distance in the shortest time. But that is not the only way to test who is the fastest. The most obvious alternative is to switch the roles of the two variables: fix a time and see who can go the farthest in that span of time.

Once you think of that the next question to ask is, does it matter? That is, if the purpose of the race is to generate a ranking of the contestants (first place, second place, etc) then are there rankings that can be generated using a fixed-time race that cannot be replicated using an appropriately chosen fixed-distance race?

I thought about this and here is a simple way to formalize the question. Below I have represented three racers. A racer is characterized by a curve which shows for every distance how long it takes him to complete that distance.

Now a race can be represented in the same diagram. For example, a standard fixed-distance race looks like this.

The vertical line indicates the distance and we can see that Green completes that distance in the shortest time, followed by Black and then Blue. So this race generates the ranking Green>Black>Blue. A fixed-time race looks like a horizontal line:

To determine the ranking generated by a fixed-time race we move from right to left along the horizontal line. In this time span, Black runs the farthest followed by Green and then Blue.

(You may wonder if we can use the same curve for a fixed-time race. After all, if the racers are trying to go as far as possible in a given length of time they would adjust their strategies accordingly. But in fact the exact same curve applies. To see this suppose that Blue finishes a d-distance race in t seconds. Then d must be the farthest he can run in t seconds. Because if he could run any farther than d, then it would follow that he can complete d in less time than t seconds. This is known as duality by the people who love to use the word duality.)

OK, now we ask the question. Take an arbitrary fixed-time race, i.e. a horizontal line, and the ordering it generates. Can we find a fixed-distance race, i.e. a vertical line that generates the same ordering? And it is easy to see that, with 3 racers, this is always possible. Look at this picture:

To find the fixed-distance race that would generate the same ordering as a given fixed-time race, we go to the racer who would take second place (here that is Black) and we find the distance he completes in our fixed-time race. A race to complete that distance in the shortest time will generate exactly the same ordering of the contestants. This is illustrated for a specific race in the diagram but it is easy to see that this method always works.

However, it turns out that these two varieties of races are no longer equivalent once we have more than 3 racers. For example, suppose we add the Red racer below.

And consider the fixed-time race shown by the horizontal line in the picture. This race generates the ordering Black>Green>Blue>Red. If you study the picture you will see that it is impossible to generate that ordering by any vertical line. Indeed, at any distance where Blue comes out ahead of Red, the Green racer will be the overall winner.

Likewise, the ordering Green>Black>Red>Blue which is generated by the fixed-distance race in the picture cannot be generated by any fixed-time race.

So, what does this mean?

- The choice of race format is not innocuous. The possible outcomes of the race are partially predetermined what would appear to be just arbitrary units of measurement. (Indeed I would be a world class sprinter if not for the blind adherence to fixed-distance racing.)

- There are even more types of races to consider. For example, consider a ray (or any curve) drawn from the origin. That defines a race if we order the racers by the first point they cross the curve from below. One way to interpret such a race is that there is a pace car on the track with the racers and a racer is eliminated as soon as he is passed by the pace car. If you play around with it you will see that these races can also generate new orderings that cannot be duplicated. (We may need an assumption here because duality by itself may not be enough, I don’t know.)

- That raises a question which is possibly even a publishable research project: What is a minimal set of races that spans all possible races? That is, find a minimal set of races such that if there is any group of contestants and any race (inside or outside the minimal set) that generates some ordering of those contestants then there is a race in the set which generates the same ordering.

- There are of course contests that are time based rather than quantity based. For example, hot dog eating contests. So another question is, if you have to pick a format, then which kinds of feats better lend themselves to quantity competition and which to duration competition?

My daughter’s 4th grade class read The Emperor’s New Clothes (a two minute read) and today I led a discussion of the story. Here are my notes.

The Emperor, who was always to be found in his dressing room, commissioned some new clothes from weavers who claimed to have a magical cloth whose fine colors and patterns would be “invisible to anyone who was unfit for his office, or who was unusually stupid.”

Fast forward to the end of the story. Many of the Emperor’s most trusted advisors have, one by one, inspected the clothes and faced the same dilemma. Each of them could see nothing and yet for fear of being branded stupid or unfit for office each bestowed upon the weavers the most elaborate compliments they could muster. Finally the Emperor himself is presented with his new clothes and he is shocked to discover that they are invisible only to him.

Am I a fool? Am I unfit to be the Emperor? What a thing to happen to me of all people! – Oh! It’s very pretty,” he said. “It has my highest approval.” And he nodded approbation at the empty loom. Nothing could make him say that he couldn’t see anything.

The weavers have succesfully engineered a herd. For any inspector who doubts the clothes’ authenticity, to be honest and dispel the myth requires him to convince the Emperor that the clothes are invisible to everybody. That is risky because if the Emperor believes the clothes are authentic (either because he sees them or he thinks he is the only one who does not) then the inspector would be judged unfit for office. With each successive inspector who declares the clothes to be authentic the evidence mounts, making the risk to the next inspector even greater. After a long enough sequence no inspector will dare to deviate from the herd, including the Emperor himself.

The clothes and the herd are a metaphor for authority itself. Respect for authority is sustained only because others‘ respect for authority is thought to be sufficiently strong to support the ouster of any who would question it.

But whose authority? The deeper lesson of the story is a theory of the firm based on the separation of ownership and management. Notice that it is the weavers who capture the rents from the environment of mutual fear that they have created. They show that the optimal use of their asset is to clothe a figurehead in artificial authority and hold him in check by keeping even him in doubt of his own legitimacy. The herd bestows management authority on the figurehead but ensures that rents flow to the owners who are surreptitiously the true authorities.

The swindlers at once asked for more money, more silk and gold thread, to get on with the weaving. But it all went into their pockets. Not a thread went into the looms, though they worked at their weaving as hard as ever.

The story concludes with a cautionary note. The herd holds together only because of calculated, self-interested subjects. The organizational structure is vulnerable if new members are not trained to see the wisdom of following along.

“But he hasn’t got anything on,” a little child said.

“Did you ever hear such innocent prattle?” said its father. And one person whispered to another what the child had said, “He hasn’t anything on. A child says he hasn’t anything on.”

“But he hasn’t got anything on!” the whole town cried out at last.

Herds are fragile because knowledge is contagious. As the organization matured everyone secretly has come to know that the authority is fabricated. And later everyone comes to know that everyone has secretly come to know that. This latent higher-order knowledge requires only a seed of public knowledge before it crystalizes into common knowledge that the organization is just a mirage.

And after that, who is the last member to maintain faith in the organization?

The Emperor shivered, for he suspected they were right. But he thought, “This procession has got to go on.” So he walked more proudly than ever, as his noblemen held high the train that wasn’t there at all.

I am always surprised in Spring how suddenly there are cars parked on the residential streets in my town where just a month ago the streets were empty. These are narrow streets so a row of cars turns it into a one-lane street that supposed to handle two-way traffic. And that is when we have to solve the problem of who enters the narrowed section first when two cars are coming in opposite directions on the street.

On my street cars are only allowed to park on the North side. So if I am headed West I have to move to the oncoming traffic side to pass the row of parked cars. If I do that and the car coming in the opposite direction has to stop for just a second or two, the driver will be understanding (a quick royal wave on the way by helps!) But if she has to wait much longer than that she is not going to be happy. And indeed the convention on my street would have me stop and wait even if I arrive at the bottleneck first.

But of course, from an efficiency point of view it shouldn’t matter which side the cars are parked on. Total waiting time is minimized by a first-come first-served convention. And note that there aren’t even distributional conseqeuences because what goes West must go East eventually.

Still the payoff-irrelevant asymmetry seems to matter. For example, a driver headed West would never complain if he arrives second and is made to wait. And because of the strict efficiency gains this is not the same as New York on the left, London on the right. The perceived property right makes all the difference. And even I, who understands the efficiency argument, adhere to the convention.

Of course there is the matter of the gap. If the Westbound driver arrives just moments before the Eastbound driver then in fact he is forced to stop because at the other end he will be bottled in. There won’t be enough room for the Westbound driver to get through if the Eastbound driver has not stopped with enough of a gap.

And once you notice this you see that in fact the efficient convention is very difficult to maintain, especially when it’s a long row of cars. The efficient convention requires the Westbound driver to be able to judge the speed of the oncoming car as well as the current gap. And the reaction time of the Eastbound driver is an unobservable variable that will have to be factored in.

That ambiguity means that there is no scope for agreement on just how much of headstart the Eastbound driver should be afforded. Especially because if he is forced to back up, he will be annoyed with good reason. So for sure the second best will give some baseline headstart to the Eastbound driver.

Then there’s the moral hazard problem. You can close the gap faster by speeding up a bit on the approach. And even if you don’t speed up, any misjudgement of the gap raises the suspicion that you did speed up, bolstering the Eastbound driver’s gripe. Note that the moral hazard problem is not mitigated by a convention which gives a longer headstart to the Eastbound driver. No matter what the headstart is, in those cases where the headstart is binding the incentive to speed up is there.

All things considered, the property rights convention, while inefficient from a first-best point of view, may in fact be the efficient one when the informational asymmetry and moral hazard problems are taken into account.

The MILQs at Spousonomics riff on the subject of “learned incompetence.” It’s the strategic response to comparative advantage in the household: if I am supposed to specialize in my comparative advantage I am going to make sure to demonstrate that my comparative advantage is in relaxing on the couch. Examples from Spousonomics:

Buying dog food. My husband has the number of the pet food store that delivers and he knows the size of the bag we buy. It would be extremely inconvenient for me to ask him for that number.

Sweeping the patio. He’s way better at getting those little pine tree needles out of the cracks. I don’t know how he does it!

A related syndrome is learned ignorance. It springs from the marital collective decision-making process. Let’s say we are deciding whether to spend a month in San Diego. Ideally we should both think it over, weigh and discuss the costs and benefits and come to an agreement. But what’s really going to happen is I am going to say yes without a moment’s reflection and her vote is going to be the pivotal one.

The reason is that, for decisions like this that require unanimity, my vote is only going to count when she is in favor. Now she loves San Diego, but she doesn’t surf and so she can’t love it nearly as much as me. So she’s going to put more weight on the costs in her cost-benefit calculation. I care about costs too but I know that conditional on she being in favor I am certainly in favor too.

Over time spouses come to know who is the marginal decision maker on all kinds of decisions. Once that happens there is no incentive for the other party to do any meaningful deliberation. Then all decisions are effectively made unilaterally by the person who is least willing to deviate from the status quo.

I wrote last week about More Guns, Less Crime. That was the theory, let’s talk about the rhetoric.

Public debates have the tendency to focus on a single dimension of an issue with both sides putting all their weight behind arguments on that single front. In the utilitarian debate about the right to carry concealed weapons, the focus is on More Guns, Less Crime. As I tried to argue before, I expect that this will be a lost cause for gun control advocates. There just isn’t much theoretical reason why liberalized gun carry laws should increase crime. And when this debate is settled, it will be a victory for gun advocates and it will lead to a discrete drop in momentum for gun control (that may have already happened.)

And that will be true despite the fact that the real underlying issue is not whether you can reduce crime (after all there are plenty of ways to do that,) but at what cost. And once the main front is lost, it will be too late for fresh arguments about externalities to have much force in public opinion. Indeed, for gun advocates the debate could not be more fortuitously framed if the agenda were set by a skilled debater. A skilled debater knows the rhetorical value of getting your opponent to mount a defense and thereby implicitly cede the importance of a point, and then overwhelming his argument on that point.

Why do debates on inherently multi-dimensional issues tend to align themselves so neatly on one axis? And given that they do, why does the side that’s going to lose on those grounds play along? I have a theory.

Debate is not about convincing your opponent but about mobilizing the spectators. And convincing the spectators is neither necessary nor sufficient for gaining momentum in public opinion. To convince is to bring others to your side. To mobilize is to give your supporters reason to keep putting energy into the debate.

The incentive to be active in the debate is multiplied when the action of your supporters is coordinated and when the coordination among opposition is disrupted. Coordinated action is fueled not by knowledge that you are winning the debate but by common knowledge that you are winning the debate. If gun control advocates watch the news after the latest mass killing and see that nobody is seriously representing their views, they will infer they are in the minority and give up the fight even if in fact they are in the majority.

Common knowledge is produced when a publicly observable bright line is passed. Once that single dimension takes hold in the public debate it becomes the bright line: When the dust is settled it will be common knowledge who won. A second round is highly unlikely because the winning side will be galvanized and the losing side demoralized. Sure there will be many people, maybe even most, who know that this particular issue is of secondary importance but that will not be common knowledge. So the only thing to do is to mount your best offense on that single dimension and hope for a miracle or at least to confuse the issue.

(Real research idea for the vapor mill. Conjecture: When x and y are random variables it is “easier” to generate common knowledge that x>0 than to generate common knowledge that x>y.)

Chickle: Which One Are You Talking About? from www.f1me.net.

Whenever I teach the Vickrey auction in my undergraduate classes I give this question:

We have seen that when a single object is being auctioned, the Vickrey (or second-price) auction ensures that bidders have a dominant strategy to bid their true willingness to pay. Suppose there are k>1 identical objects for sale. What auction rule would extend the Vickrey logic and make truthful bidding a dominant strategy?

Invariably the majority of students give the intuitive, but wrong answer. They suggest that the highest bidder should pay the second-highest bid, the second-highest bidder should pay the third-highest bid, and so on.

Did you know that Google made the same mistake? Google’s system for auctioning sponsored ads for keyword searches is, at its core, the auction format that my undergraduates propose (plus some bells and whistles that account for the higher value of being listed closer to the top and Google’s assessment of the “quality” of the ads.) And indeed Google’s marketing literature proudly claims that it “uses Nobel Prize-winning economic theory.” (That would be Vickrey’s Nobel.)

But here’s the remarkable thing. Although my undergraduates and Google got it wrong, in a seemingly miraculous coincidence, when you look very closely at their homebrewed auction, you find that it is not very different at all from the (multi-object) Vickrey mechanism. (In case you are wondering, the correct answer is that all of the k highest bidders should pay the same price: the k+1st highest bid.)

In a famous paper, Edelman, Ostrovsky and Schwarz (and contempraneously Hal Varian) studied the auction they named The Generalized Second Price Auction (GSPA) and showed that it has an equilibrium in which bidders, bidding optimally, effectively undo Google’s mistaken rule and restore the proper Vickrey pricing schedule. It’s not a dominant strategy, but it is something pretty close: if everyone bids this way no bidder is going to regret his bid after the auction is over. (An ex post equilibrium.)

Interestingly this wasn’t the case with the old style auctions that were in use prior to the GSPA. Those auctions were based on a first-price model in which the winners paid their own bids. In such a system you always regret your bid ex post because you either bid too much (anything more than your opponents’ bid plus a penny is too much) or too little. Indeed, advertisers used software agents to modify their standing bids at high-frequencies in order to minimize these mistakes. In practice this meant that auction outcomes were highly volatile.

So the Google auction was a happy accident. On the other hand, an auction theorist might say that this was not an accident at all. The real miracle would have been to come up with an auction that didn’t somehow reduce to the Vickrey mechanism. Because the revenue equivalence theorem says that the exact rules of the auction matter only insofar as they determine who the winners are. Google could use any mechanism and as long as its guaranteed that the bidders with the highest values will win, that can be accomplished in an ex post equilibrium with the bidders paying exactly what they would have paid in the Vickrey mechanism.

Check out Michael Chwe’s book Folk Game Theory: Strategic Analysis in Austen, Hammerstain, and African American Folk Tales. It’s a study of game theory in the context of literature and of literature through the lens of game theory. But it’s more than that. Each of the stories in the book illustrates what happens out of equilibrium.

The fox gets tricked by the rabbit because the fox has not understood the strategic motivation behind the rabbit’s actions. The master pays the price when he underestimates the slave. A folk tale is an artificially constructed scenario which purposefully takes the characters off the equilibrium path in order to teach us to stay on it.

By recovering a “people’s history of game theory” and gaining a larger understanding of its past, we enlarge its potential future. Game theory’s mathematical models are sometimes criticized for assuming ahistorical, decontextualized actors, and indeed game theory is typ- ically applied to relatively “neutral” situations such as auctions and elections. Folk game theory shows that game theory can most inter- estingly arise in situations which are strongly gendered or racialized, with clear superiors and subordinates. By looking at slave folktales, we can see how the story of Flossie and the Fox is a sophisticated discus- sion of deterrence. We can see from Austen’s heroine Fanny Price that social norms, far from protecting sociality against the corrosive forces of individualism, can be the first line of oppression. We can see from Hammerstein’s Ado Annie how convincing others of your impulsive- ness can open up new strategic opportunities. Folk game theory has wisdom which can be explored just as traditional folk medicines are now investigated by pharmaceutical companies.

In economic theory, the study of institutions falls under the general heading of mechanism design. An institution is modeled as game in which the relevant parties interact and influence the final outcome. We study how to optimally design institutions by considering how changes in the rules of the game change the way participants interact and bring about better or worse outcomes.

But when the new leaders in Egypt sit down to design a new constitution for the country, standard mechanism design will not be much help. That’s because all of mechanism design theory is premised on the assumption that the planner has in front of him a set of feasible alternatives and he is desigining the game in order to improve society’s decision over those alternatives. So it is perfectly well suited for decisions about how much a government should spend this year on all of the projects before it. But to design a constitution is to decide on procedures that will govern decisioins over alternatives that become available only in the future, and about which today’s Constitutional Congress knows nothing.

The American Constitutional Congress implicitly decided how much the United States would invest in nuclear weapons before any of them had any idea that such a thing was possible.

Designing a constitution raises a unique set of incentive problems. A great analogy is deciding on a restaurant with a group of friends. Before you start deliberating you need to know what the options are. Each of you knows about some subset of the restaurants in town and whatever procedure the group will use to ultimately decide affects whether or not you are willing to mention some of the restaurants you know about.

Ideally you would like a procedure which encourages everyone to name all the good restaurants they know about so that the group has as wide a set of choices as possible. But you can’t just indiscriminately reward people for bringing alternatives to the table because that would only lead to a long list of mostly lousy choices.

You can only expect people to suggest good restaurants if they believe that the restaurants they suggest have a chance of being chosen. And now you have to worry about strategic behavior. If I know a good Chinese restaurant but I am not in the mood for Chinese, then how are you going to reward me for bringing it up as an option?

When we think about institutions for public decisions, we have to take into account how they impact this strategic problem. Democracy may not be the best way to decide on a restaurant. If the status quo, say the Japanese restaurant is your second-favorite, you may not suggest the Mexican restaurant for fear that it will split the vote and ultimately lead to the Moroccan restaurant, your least favorite.

Certainly such political incentives affect modern day decision-making. Would a better health-care proposal have materialized were it not for fear of what it would be turned into by the political sausage mill?

Following up on the Trivers-Willard hypothesis. The evidence is apparently that promiscuity, a trait that confers more reproductive advantage on males than females, is predictive of a greater than 50% probability of male offspring. A commenter claimed that there is a bias in favor of male offspring when the mother is impregnated close to ovulation and wondered whether the study controlled for that. A second commenter pointed out that there is no reason to control for that because that may be exactly the channel through which the Trivers-Willard effect works.

So now put yourself in the shoes of the intelligent designer. Suppose you are given that promiscuity is such a trait. You are given control over the male-female proportion of offspring and you are designing the female of the species. What you want to do is program her to have male offspring when she mates with a promiscuous male. But you cannot micromanage because there is no way to condition this directly on the promiscuity of the mate. The best you can do is vary the sex proportions conditional on biological signals, for example the date in the cycle.

How would you do this? Of all the “states of the system” that you can condition on, you would find the one such that conditional on having sex in that state, the relative likelihood that her partner was the promiscuous type was maximized. You would program her to increase the proportion of male offspring in those states.

Is sex close to ovulation such a signal? I don’t see why. But we could think of some that would qualify. How about the signal that he is delivering a small quantity of sperm? The encounter lasted longer than usual, this is the first time she had sex in a while, these sperm have not been seen before, etc…

Here’s a broad class of games that captures a typical form of competition. You and a rival simultaneously choose how much effort to spend and depending on your choices, you earn a score, a continuous variable. The score is increasing in your effort and decreasing in your rival’s effort. Your payoff is increasing in your score and decreasing in your effort. Your rival’s payoff is decreasing in your score and his effort.

In football, this could model an individual play where the score is the number of yards gained. A model like this gives qualitatively different predictions when the payoff is a smooth function of the score versus when there are jumps in the payoff function. For example, suppose that it is 3rd down and 5 yards to go. Then the payoff increases gradually in the number of yards you gain but then jumps up discretely if you can gain at least 5 yards giving you a first down. Your rival’s payoff exhibits a jump down at that point.

If it is 3rd down and 20 then that payoff jump requires a much higher score. This is the easy case to analyze because the jump is too remote to play a significant role in strategy. The solution will be characterized by a local optimality condition. Your effort is chosen to equate the marginal cost of effort to the marginal increase in score, given your rival’s effort. Your rival solves an analogous problem. This yields an equilibrium score strictly less than 20. (A richer, and more realistic model would have randomness in the score.) In this equilibrium it is possible for you to increase your score, even possibly to 20, but the cost of doing so in terms of increased effort is too large to be profitable.

Suppose that in the above equilibrium you gain 4 yards. Then when it is 3rd down and 5 this equilibrium will unravel. The reason is that although the local optimality condition still holds, you now have a profitable global deviation, namely putting in enough effort to gain 5 yards. That deviation was possible before but unprofitable because 5 yards wasn’t worth much more than 4. Now it is.

Of course it will not be an equilibrium for you to gain 5 yards because then your opponent can increase effort and reduce the score below 5 again. If so, then you are wasting the extra effort and you will reduce it back to the old value. But then so will he, etc. Now equilibrium requires mixing.

Finally, suppose it is 3rd down and inches. Then we are back to a case where we don’t need mixing. Because no matter how much effort your opponent uses you cannot be deterred from putting in enough effort to gain those inches.