You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘game theory’ tag.

You need a lot of chessboards for this one, but on top of winning some money you will impress your pals. Challenge a large even number of people to play chess simultaneously and blindfolded. Ask for 2-1 odds against each opponent. Play White against half and Black against the other half. Even if your chess is crap, you are guaranteed to make money.

Here’s how. You mentally associate each game you are playing White with a game in which you are playing Black. You start with the opponents against whom you are playing Black and you remember their moves. Then when you arrive at the associated board in which you are playing White, you just copy the move from the other board. Wait for the response and then copy that move on the associated board in which you are playing Black. Keep doing this. You are effectively making each associated pair play each other. You will average a draw on each pair and so with 2-1 odds you will make money.

All that is required from this is to be able to keep a few moves in your head. If you can do that, you can do this blindfolded and really make an impression. If your memory isn’t up to that, you can skip the blindfold and use the board positions as a mnemonic to help you remember.

Here is a video of this trick in action from Derren Brown.

After showing how the Vickrey auction efficiently allocates a private good we revisit some of the other social choice problems discussed at the beginning and speculate how to extend the Vickrey logic to those problems. We look at the auction with externalities and see how the rules of the Vickrey auction can be modified to achieve efficiency. At first the modification seems strange, but then we see a theme emerge. Agents should pay the negative externalities they impose on the rest of society (and receive payment in compensation for the postive externalities.

We distill this idea into a general formula which measures these externalities and define a transfer function according to that formula. The resulting efficient mechanism is called the Vickrey-Clarke-Groves mechanism. We show that the VCG mechanism is dominant-strategy incentive compatible and we show how it works in a few examples.

We conclude by returning to the roomate/espresso machine example. Here we explicitly calculate the contributions each roomate should make when the espresso machine is purchased. We remind ourselves of the constraint that the total contributions should cover the cost of the machine and we see that the VCG mechanism falls short. Next we show that in fact the VCG mechanism is the only dominant-strategy efficient mechanism for this problem and arrive at this lecture’s punch line.

There is no efficient, budget-balanced, dominant-strategy mechanism.

Here are the slides.

Our colleagues, Eran Shmaya and Rakesh Vohra have started a blog, The Leisure of the Theory Class. Only three posts so far, but it promises to be a feast of Gale-Stewart games, and gossip. I look forward to them making fun of Sandeep too.

Not Exactly Rocket Science describes an experiment in which vervet monkeys are observed to trade grooming favors for fruit. At first one of the monkeys had an exclusive endowment of fruit and earned a monopoly price. Next, competition was introduced. The endowment was now equally divided between two duopolist monkeys and as a result the price in terms of willingness-to-groom dropped.

Now, were the monkeys playing Cournot (marginal cost equals residual marginal revenue) or Bertrand (price equals marginal cost)? (The marginal cost of trading an apple for a grooming session is the opportunity cost of not eating it.) We need another treatment with three sellers to know. If the price falls even further then its Cournot. In Bertrand the price hits the competitive point already with just two.

Intermediate micro question: Can Monkey #1 increase his profits by buying the apples from Monkey #2 at the equilibrium price and then acting as a monopolist?

We will take a first glimpse at applying game theory to confront the incentive problem and understand the design of efficient mechanisms. The simplest starting point is the efficient allocation of a single object. In this lecture we look at efficient auctions. I start with a straw-man: the first-price sealed bid auction. This is intended to provoke discussion and get the class to think about the strategic issues bidders face in an auction. The discussion reaches the conclusion that there is no dominant strategy in a first-price auction and it is hard to predict bidders’ behavior. For this reason it is easy to imagine a bidder with a high value being outbid by a bidder with a low value and this is inefficient.

The key problem with the first-price auction is that bidders have an incentive to bid less than their value to minimize their payment, but this creates a tricky trade-off as lower bids also mean an increased chance of losing altogether. With this observation we turn to the second-price auction which clearly removes this trade-off altogether. On the other hand it seems crazy on its face: if bidders don’t have to put their money whether mouths are won’t they now want to go in the other direction and raise their bid above their value?

We prove that it is a dominant strategy to bid your value in a second-price auction and that the auction is therefore an efficient mechanism in this setting.

Next we explore some of the limitations of this result. We look at externalities: it matters not just whether I get the good, but also who else gets it in the event that I don’t. We see that a second-price auction is not efficient anymore. And we look at a setting with common values: information about the object’s value is dispersed among the bidders.

For the comon-value setting I do a classroom experiment where I auction an unknown amount of cash. The amount up for sale is equal to the average of the numbers on 10 cards that I have handed out to 10 volunteers. Each volunteer sees only his own card and then bids. If the experiment works (it doesnt always work) then we should see the winner’s curse in action: the winner will typically be the person holding the highest number, and bidding something close to that number will lose money as the average is certainly lower.

Here are the slides.

(I got the idea from the winner’s curse experiment from Ben Polak, who auctions a jar of coins in his game theory class at Yale. Here is a video. Here is the full set of Ben Polak’s game theory lectures on video. They are really outstanding. Northwestern should have a program like this. All Universities should.)

Wimbledon, which has just gotten underway today, is a seeded tournament, like all major tennis events and other elimination tournaments. Competitors are ranked according to strength and placed into the elimination bracket in a way that matches the strongest against the weakest. For example, seeding is designed so that when the quarter-finals are reached, the top seed (the strongest player) will face the 8th seed, the 2nd seed will face the 7th seed, etc. From the blog Straight Sets:

When Rafael Nadal withdrew from Wimbledon on Friday, there was a reshuffling of the seeds that may have raised a few eyebrows. Here is how it was explained on Wimbledon.org:

The hole at the top of the men’s draw left by Nadal will be filled by the fifth seed, Juan Martin del Potro. Del Potro’s place will be taken by the 17th seed James Blake of the USA. The next to be seeded, Nicolas Kiefer moves to line 56 to take Blake’s position as the 33rd seed. Thiago Alves takes Kiefer’s position on line 61 and is a lucky loser.

Was this simply Wimbledon tweaking the draw at their whim or was there some method to the madness?

Presumably tournaments are seeded in order to make them as exciting as possible for the spectators. One plausible goal is to maximize the chances that the top two players meet in the final, since viewership peaks considerably for the final. But the standard seeding is not obviously the optimal one for this objective: it makes it easy for the top seed to make the final but hard for the second seed. Switching the positions of the top ranked and second ranked players might increase the chances of having a 1-2 final.

You would also expect that early round matches would be more competitive. Competitiveness in contests, like tennis matches, is determined by the relative strength of the opponents. Switching the position of 1 and 2 would even out the matches played by the top player at the expense of unbalancing the matches played by the second player, the average balance across matches would be unchanged. If effort is concave in the relative strength of the opponents then the total effect would be to increase competitiveness.

When you start thinking about the game theory of tournaments, your first thought is what has Benny Moldovanu said on the subject. And sure enough, google turns up this paper by Groh, Moldovanu, Sela, and Sunde which seems to have all the answers. Incidentally, Benny will be visiting Northwestern next fall and I expect that he will be bringing his tennis racket…

In an old post, I half-jokingly suggested that the rules of scrabble should be changed to allow the values of tiles to be determined endogenously by competitive bidding. PhD students, thankfully, are not known for their sense of humor and two of Northwestern’s best, Mallesh Pai and Ben Handel, took me seriously and drafted a set of rules. Today we played the game for the first time. (Mallesh couldn’t play because he is traveling and Kane Sweeney joined Ben and me.)

Scrabble normally bores me to tears but I must say this was really fun. The game works roughly as follows. At the beginning of the game tiles are turned over in sequence and the players bid on them in a fixed order. The high bidder gets the tile and subtracts his bid from his total score. (We started with a score of 100 and ruled out going negative, but this was never binding. An alternative is to start at zero and allow negative scores.) After all players have 7 tiles the game begins. In each round, each player takes a turn but does not draw any tiles at the end of his turn. At the end of the round, tiles are again turned over in sequence and bidding works just as at the beginning until all players have 7 tiles again, and the next round begins. Apart from this, the rules are essentially the standard scrabble rules.

Since each players’ tiles are public information, we decided to take memory out of the game and have the players keep their tiles face up. It also makes for fun kibbitzing. The complete rules are here. Share and enjoy! Here are some notes from our first experiment:

- The relative (nominal) values of tiles are way out of line of their true value. The way to measure this is to compare the “market” price to the nominal value. If the market price is higher that means that players are willing to give up more points to get the tile than that tile will give them back when played (ignoring tile-multipliers on the board.) That means that the nominal score is too high. For example, blanks have a nominal score of zero. But the market price of a blank in our play was about 20 points. This is because blanks are “team players:” very valuable in terms of helping you build words. So, playing by standard scrabble rules with no bidding, if the value of a blank was to be on equal terms with the value of other tiles, blanks should score negative: you should have to pay to use them. Other tiles whose value is out of line: s (too high, should be negative), u(too low), v(too low.) On the other hand, the rare letters, like X, J, Z, seem to be reasonably scored.

- Defense is much more a part of the game. This is partly because there is more scope for defense by buying tiles to keep them from the opponent, but also in terms of the play because you see the tiles of the opponents.

- It is much easier to build 7/8 letter words and use all your tiles. This should be factored into the bidding.

- There are a few elements of bidding strategy that you learn pretty quickly. They all have to do with comparing the nominal value of the tile up for auction with the option value of losing the current auction and bidding on the next, randomly determined, tile. This strategy becomes especially interesting when your opponent will win his 7th tile, forcing you the next tile(s) but at a price of zero.

- Because the game has much less luck than standard scrabble, differences in ability are amplified. This explains why Ben kicked our asses. But with three players, there is an effect which keeps it close: the bidding tends to favor the player who is behind because the leaders are more willing to allow the trailer to win a key tile than the other leader.

Finally, we have some theoretical questions. First, suppose there is no lower bound to your score, so that you are never constrained from bidding as much as you value for a tile, the initial score is zero, and there are two players playing optimal strategies. Is the expected value of the final score equal to zero? In other words, will all scoring be bid away on average? Second, to what extent do the nominal values of the tiles matter for the play of the game. For example, if all values are multiplied by a constant does this leave the optimal strategy unchanged?

Now we have set the stage. We are considering social choice problems with transferrable utility. We want to achieve Pareto efficient outcomes which in this context is equivalent to utilitarianism.

Now we face the next problem. How do we know what the efficient policy is? It of course depends on the preferences of individuals and any institution must implicitly involve providing a medium through which preferences are communicated and mediated. In this lecture I introduce this idea in the context of a simple example.

Two roomates are condering purchasing an espresso machine. The machine costs $50. Each has a maximum willingness to pay, but each knows only his own willingness to pay and not the others. It is efficient to buy the machine if and only if the sum exceeds $50. They have to decide two things: whether or not to buy the machine and how to share the cost. I ask the class what they would do in this situation.

A natural proposal is to share the cost equally. I show that this is inefficient because it may be that one roomate has a high willingness to pay, say $40, and the other has a low willingness to pay, say $20. The sum exceeds $50 but one roomate will reject splitting the cost. This leads to discussion of how to improve the mechanism. Students propose clever mechanisms and we work out how each of them can be manipulated and we discover the conflict between efficiency and incentive-compatibility. There is scope for some very engaging class discussions here that create a good mindset for the coming more careful treatment.

At this stage I tell the students that these mechanisms create something like a game played by the roomates and if we are going to get a good handle on how institutions perform we need to start by developing a theory of how people play games like this. So we will take a quick detour into game theory.

For most of this class, very little game theory is necessary. So I begin by giving the basic notation and defining dominated and dominant strategies. I introduce all of these concepts through a hilarious video: The Golden Balls Split or Steal Game (which I have blogged here before.) I play the beginning video to setup the situation, then pause it and show how the game described in the video can be formally captured in our notation. Next I play the middle of the video where the two players engage in “pre-play communication.” I pause the video and have a discussion about what the players should do and whether they think that communication should matter. I poll the class on what they would do and what they predict the two players will do. Then I show them the dominant strategies.

Finally I play the conclusion of the video. Its a pretty fun moment. I conclude with a game to play in class. This year I had just started using Twitter and I came up with a fun game to play on Twitter. I blogged about this game previously.

(By the way this game is extremely interesting theoretically. I am pretty confident that this game would always succeed in implementing the desired outcome: getting the target number of players to sign up, but it is not easy to analyze because of the continuous time nature. The basic logic is this: if you think that the target will not be met, then you should sign up immediately. But then the target will be met.)

Here are the lecture slides.

Thursday night we had another overtime game in the NBA finals. For the sake of context, here is a plot of the time series of point differential. Orlando minus LA.

A few of the commenters on the previous post nailed the late-game strategy behind the eye-popping animation. First, at the end of the game, the team that is currently behind will intentionally foul in order to prevent the opponent running out the clock. The effect of this in terms of the histogram is that it throws mass out away from zero. But the ensuing free-throws might be missed and this gives the trailing team a chance to close the gap. So the total effect of this strategy is to throw mass in both directions.

If the trailing team is really lucky both free throws will be missed and they will score on the subsequent possession and take the lead. Now the other team is trailing and they will do the same. So we see that at the end of the game, no matter where we are on that histogram, mass will be thrown in both directions, until either the lead is insurmountable, or we land right at zero, a tie game.

Once the game is tied there is no more incentive to foul. But there is also no incentive to shoot (assuming less than 24 seconds to go.) The leading team will run the clock as far as possible before taking one last shot.

So there are two reasons for the spike: risk-taking strategy by the trailing team increases the chance of landing at a tie game, and then conservative strategy keeps us there. The following graphic (again due to the excellent Toomas Hinnosaar) illustrates this pretty clearly.

In blue you have the distribution of point differences that we would get if we pretented that the teams’ scoring was uncorrelated. This is what I referred to as the crude hypothesis in the previous post. In red you see the extra mass from the actual distribution and in white you see the smaller mass from the actual distribution. We see that the actual distribution is more concentrated in the tails (because there is less incentive to keep scoring when you are already very far ahead), less concentrated around zero (because of risk-taking by the trailing team) and much more concentrated at the point zero (because of conservative play when the game is tied.)

In blue you have the distribution of point differences that we would get if we pretented that the teams’ scoring was uncorrelated. This is what I referred to as the crude hypothesis in the previous post. In red you see the extra mass from the actual distribution and in white you see the smaller mass from the actual distribution. We see that the actual distribution is more concentrated in the tails (because there is less incentive to keep scoring when you are already very far ahead), less concentrated around zero (because of risk-taking by the trailing team) and much more concentrated at the point zero (because of conservative play when the game is tied.)

Now, this is all qualitatively consistent with the end-of-regulation histogram and with the animation. The big question is whether it can explain the size of that spike quantitatively. Obviously, not all games that go into overtime follow this pattern. For example, Thursday’s game did not feature intentional fouling at the end. How can we assess whether sound strategy alone is enough to explain the frequency of overtime?

There have been quite a few overtime games in the NBA playoffs this year. We have had one in the finals already and in an earlier series between the Bulls and Celtics, 4 out of 7 games went into overtime, with one game in double overtime and one game in triple overtime!

How often should we expect a basketball game to end tied after 48 minutes of play? At first glance it would seem pretty rare. If you look at the distribution of points scored by the home teams and by the visiting teams separately, they look pretty close to a normal distribution with a large variance. If we made the crude hypothesis that the two distributions were statistically independent, then ties would indeed be very rare: 2.29% of all games would reach overtime.

But the scoring is not independent of course. Similar to a marathon, the amount of effort expended is different for the team currently in front versus the team trailing and this amount of effort also depends on the current point differential. But such strategy should have only a small effect on the probability of ties. The team ahead optimally slows down to conserve effort, balancing this against the increased chance that the score will tighten. Also, conservation of effort by itself should generally compress point differentials, raising not just the frequency of ties, but also the frequency of games decided by one or two points.

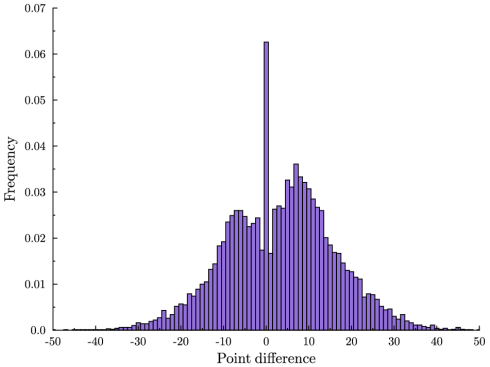

But overtime is almost 3 times more frequent than this: 6.26% of all NBA games are tied at the end of regulation play. And games decided by just a few points are surprisingly rare: It is more likely to have a tie than for the game to be decided by two points, and a tie is more than twice as likely as a one-point difference. These statistics are quite dramatic when you see them visually.

Here is a frequency histogram of the difference in points between the home team and visiting team at the end of regulation play. These are data from all NBA games 1997-2009. A positive number means that the home team won, a zero means that the game was tied and therefore went into overtime. Notice the massive spike at zero.

(There is also more mass on the positive end. This is the well-known home team bias.)

What explains this? A star PhD student at Northwestern, Toomas Hinnosaar, and I have been thinking about this. Our focus in on the dynamics and strategy at the end of the game. To give you some ideas, Toomas created the following striking video. It shows the evolution of the point differential in the last 40 seconds of the fourth quarter. At the beginning, the distribution looks close to normal. This is what the crude hypothesis above would predict. Watch how the spike emerges in such a short period of time.

By contrast, here is the same animation at the end of halftime. Nothing unusual.

My yoga teacher begins class instructing us to moderate our breathing. Her precise instruction is this: breathe loud enough so that your neighbor can hear you breathe but not so loud that you cannot hear your neighbor’s breath.

How loud should I breathe?

Today at Peet’s in Evanston I was trying to work out a model for this idea Sandeep and I are working on related to the game theory of torture. I started drawing a litle graph and then got lost in thought. I must have looked a little weird (nothing unusual there) because the woman next to me started asking me what was up with this squiggly plot on my pad of paper.

Most economists dread these moments when someone asks you what you do and you have to tell them you’re an economist and then prepare to deflect the inevitable questions and/or accusations “what’s going to happen with interest rates?” “when’s the economy going to turn around?” Usually I just mumble and wait for the person to get bored and go on with her reading. For some reason I was talkative today.

I told her I was a game theorist. “What’s that for?” I told her I was working on a theory of torture. She looked horrified. “How do you make a theory of torture?”

I told her that using game theory is a lot like screenwriting. Imagine you were a film-maker and you wanted to make a point about torture. You would invent characters and put them in the roles of torturer and torturee and you would describe the events. You would depict how the torturer would plan his torture and how he would the torturee would react and how this would lead the torturer to adjust his approach. If the film was going to be effective it would have believable characters and it would have to show the audience a plausible hypothetical situation and what happens when these characters act out their roles in that situation. In short, its a model.

(As I was saying this I remembered that I learned to think of economics and literature in this way about 20 years ago from Tyler Cowen. And he has a nice paper on it here.)

She looked even more horrified. But I was pretty pleased. I started thinking about Resevoir Dogs (nsfw).

While scripts and models are constrained by a similar requirement of coherence between character and events, there are differences and this makes them complementary. A model necessarily maps out the entire game tree, while a script describes just one path. In a model every counterfactual is analyzed and we see their consequences and this explains why those paths are not taken, but a film is a far more vivid account of the path taken. In a model the off-equilibrium outcomes are the results of mistakes while a well-conceived script can bring in plausible external developments to place the characters in unexpected situations.

Of course film-makers get invited to better parties.

Its a standard example of a game that has no Nash equilibrium. But what exactly are the rules of the game? How about these:

You have fifteen seconds. Using standard math notation, English words, or both, name a single whole number—not an infinity—on a blank index card. Be precise enough for any reasonable modern mathematician to determine exactly what number you’ve named, by consulting only your card and, if necessary, the published literature.

Hmm… maybe it does have a Nash equilbirium. But after reading the article (highly recommended), I am still not sure. I think it comes down to whether or not the players are Turing machines. (Fez flip: The Browser)

James Joyce’s Ulysses? The Great Gatsby? Something challenging by Thomas Pynchon? Something whimsical by P.G. Wodehouse?

No, the smart vote goes to Isaac Asimov’s Foundations Trilogy.

The latest fan to come out in public is Hal Varian. In a Wired interview, he says:

“In Isaac Asimov’s first Foundation Trilogy, there was a character who basically constructed mathematical models of society, and I thought this was a really exciting idea. When I went to college, I looked around for that subject. It turned out to be economics.”

The first time I saw a reference to the books was in an interview with Roger Myerson in 2002. And he repeated the fact that he was influenced by Foundation in an answer to a question after he got the Nobel Prize in 2007. And finally, Paul Krugman also credits the books with inspiring him to become an economist. A distinguished trio of endorsements!

Asimov’s stories revolve around the plan of Hari Seldon a “psychohistorian” to influence the political and economic course of the universe. Seldon uses mathematical methodology to predict the end of the current Empire. He sets up two “Foundations” or colonies of knowledge to reduce the length of the dark age that will follow the end of empire. The first Foundation is defeated by a weird mutant called the Mule. But the Mule fails to locate and kill the Second Foundation. So, Seldon manages to preserve human knowledge and perhaps even predicted the Mule using psychohistory. Seldon also has a keen sense of portfolio diversification – two Foundations rather than one – and also the law of large numbers – psychohistory is good at predicting events involving a large number of agents but not at forecasting individual actions.

As the above discussion reveals, I did take a stab at reading these books after I saw the Myerson inteview (though I admit I used Wikipedia liberally to jog my memory for this post!). And you can also see how Myerson’s “mechanism design” theory might have come out reading Asimov. I enjoyed reading the first book in the trilogy and it’s clear how it might excite a teenage boy with an aptitude for maths. The next two books are much worse. I struggled through them just to find out how it all ended. Perhaps I read them when I was too old to appreciate them.

The Lord of the Rings is probably wooden to someone who reads it in their forties. It still sparkles for me.

Tom Schelling has a famous example illustrating how to solve coordination problems. Suppose you are supposed to meet someone in New York City but you forgot to specify a location to meet. This was before the era of cell phones so there is no opportunity for cooperation before you pick a place to go. Where do you go? You go where your friend thinks you are most likely to go, which is of course where she thinks you think she thinks you are most likely to go, etc.

Notice that convenience or taste or proximity have no direct bearing on your choice. These considerations may indirectly influence your choice, but only if she thinks you think she thinks … that they will influence your choice.

There was an old game show called the Newlywed Game where I learned some of my very early training as a game theorist in my living room roughly at the age of 7. Here is how the show works. 4 pairs of newlyweds were competing. The husbands, say, would be on stage first, with the wives in an isolated room. The husbands would be asked a series of questions about their wives, say “What wedding gift from your family does your wife hate the most?” and the husbands would have to guess what the wives would say. (This was the 70’s so every episode had at least one question about “making whoopee,” like “what movie star would your wife say you best remind her of when you’re makin’ whoopee?”)

When you watch this show every night for as long as I did you soon figure out that the way to win this show is to disregard completely the question and just find something to say that you wife is likely to say, which is of course what she thinks you think she is likely to say, etc. You could try to make a plan with your newlywed spouse beforehand about what to say, something like the first answer is “the crock pot”, the second answer is “burt reynolds” etc. But this looks awkward when the first question turns out to be “What is your wife’s favorite room to make whoopee?” etc.

So the problem is just like Schelling’s meeting problem. The truth is of secondary importance. You want to find the most obvious answer, i.e. the one your wife is most likely to give because she thinks you are most likely to give it, etc. For example, if the question is, “Which Smurf will your wife say best describes your style of makin’ whoopee?” then even though you think the answer is probably “Clumsy Smurf” or “Sloppy Smurf”, you say “Hefty Smurf” because that is the obvious answer.

Ok, all of this is setup to tell you that Gary Becker is clearly a better game theorist than Steve Levitt. Via Freakonomics, Levitt tells the story of a Chicago economics faculty Newlywed game played at their annual skit party. (Northwestern is one of the few top departments that doesn’t have one of these. That sucks.) Becker and Levitt were newlyweds. According to Levitt they did poorly, but it looks like Becker was onto the right strategy, but Levitt was trying to figure out the right answers:

The first question was, “Who is Gary’s favorite economist?” I thought I knew this one for sure. I guessed Milton Friedman. Gary answered Adam Smith. (Although he later apologized to me and said Friedman was the right answer.)

Then they asked, “In Gary’s opinion, how many more quarters will the current recession last?” I guessed he would say three more quarters, but his actual answer was two more quarters.

The next question was, “Who does Gary think will win the next Nobel prize in economics?” This is a hard one, because there are so many reasonable guesses. I figured if Becker writes a blog with Posner, he might think Posner would win the Nobel prize, so that was my answer. Gary said Gene Fama instead.

The last question we got wrong was one that was posed to Gary, asking which of the following three people I would most like to have lunch with: Marilyn Monroe, Napolean, or Karl Marx. I know Gary has a major crush on Marilyn Monroe, so that was the answer I gave, even though the question was about who I would want to have lunch with, not who Gary would want to have lunch with. Gary answered Karl Marx (which makes me wonder what he thinks of me), but did volunteer, as I strongly suspected, that he himself would of course prefer Marilyn to either of the other two.

The French Open began on Sunday and if you are an avid fan like me the first thing you noticed is that the Tennis Channel has taken a deeper cut of the exclusive cable television broadcast in the United States. I don’t subscribe to the Tennis channel and until this year they have been only a slight nuisance, taking a few hours here and there and the doubles finals. But as I look over the TV schedule for the next two weeks I see signs of a sea change.

First of all, only the TC had the French Open on Memorial Day, yesterday. This I think was true last year as well, but now this year all of the early session live coverage for the entire tournament is exclusive on TC. ESPN2 takes over for the afternoon session and will broadcast early session games on tape.

This got me thinking about the economics of broadcasting rights. I poked around and discovered in fact that the TC owns all US cable broadcasting rights for the French Open many years to come. ESPN2 is subleasing those rights from TC for the segments they are airing. So that is interesting. Why is TC outbidding ESPN2 for the rights and then selling most of them back?

Two forces are at work here. First, ESPN2 as a general sports broadcaster has more valuable alternative uses for the air time and so their opportunity cost of airing the French Open is higher. But of course the other side is that ESPN2 can generate a larger audience just from spillovers and self-advertising than TC so their value for rights to the French Open is higher. One of these effects outweighs the other and so on net the French Open is more valuable to one of these two networks. Naively we should think that whoever that is would outbid the other and air the tournament. So what explains this hybrid arrangement?

My answer is that there is uncertainty about the TC’s ability to generate enough audience for a grand slam to make it more valuable for TC than for ESPN. In face of this TC wants a deal which allows it to experiment on a small scale and find out what it can do but also leaves it the option of selling back the rights if the news is bad. TC can manufacture such a deal by buying the exclusive rights. ESPN2 knows its net value for the French Open and will bid that value for the original rights. And if it loses the bidding it will always be willing to buy those rights at the same price on the secondary market from TC. TC will outbid ESPN2 because the value of the option is at least the resale price and in fact strictly higher if there is a chance that the news is good.

So, the fact that TC has steadily reduced the amount of time it is selling back to ESPN2 suggests that so far the news is looking good and there is a good chance that soon the TC will be the exclusive cable broadcaster for the French Open and maybe even other grand slams.

Bad news for me because in my area the TC is not broadcast in HD and so it is simply not worth the extra cost to subscribe. While we are on the subject, here is my French Open outlook

- Federer beat Nadal convincingly in Madrid last week. I expect them in the final and this could bode well for Federer.

- If there is anybody who will spoil that outcome it will be Verdasco who I believe is in Nadal’s half of the draw. The best match of the tournament will be Nadal-Verdasco if they meet.

- The Frenchmen are all fun but they don’t seem to have the staying power. Andy Murray lost a lot psychologically when he was crowing going into this year’s Australian and lost early.

- I always root for Tipsarevich. And against Roddick.

- All of the excitement on the women’s side from the past few years seems to have completely disappeared with the retirement of Henin, the injury to Sharapova and the meltdown of the Serbs. I expect a Williams-Williams yawner.

Turns out that a good way to predict how the US Supreme Court will rule is by counting the number of questions asked to either side. The winning side will be the one with the fewest questions asked. Is this because

- the justices have made up their minds already and ask more questions of the losing side, or

- more questions put the lawyer on the defensive, weakening his position?

That is, does outcome cause the questions or the other way around? I think it has to be the fomer, indeed the latter eventually implies the former. If questioning per se made a side weaker, then the justices would learn this and would realize that their questions were generating more heat than light. Once they realize this, they will know that the only way to get their side to win would be to ask more questions of the other side.

Here is an article (via MindHacks) profiling the types of people who are attracted to conspiracy theories.

It is the domain of psychology to study the specific conspiracy theories that appear and the people who advocate them, but to a game theorist the prevalence of conspiracy theories is not surprising. They fill a credibility gap. Like nature, the truth abhors a vacuum. It cannot be an equilibrium that only the truth is told and retold. Because then we would learn to believe everything we hear. That would be exploited by people trying to take advantage.

Conspiracy theories are just one example of noise that must be present in equilibrium to ensure that we don’t believe everything we hear. And arguably conspiracy theories about events that have already happened or are beyond our control are the cost-minimizing way of moderating credibility. Nobody really gets harmed.

I don’t think this is the right way to make it.

Linguine and clams is one of those dishes where insistence on simplicity is rewarded. The basic mechanics of the dish are extremely straightforward. There are just a few little secrets that elevate a good dish to an excellent one.

Obviously you want fresh clams. You don’t want fresh pasta. Dried pasta works much better here, more on that later. You want garlic, parsley is a nice touch, olive oil, butter and white wine. That’s it. (Bacon?? Sorry Sandeep, no.) Maybe red chile flakes.

Start boiling the pasta. Set the timer for 1 minute short of al dente. Heat a flat pan which can be covered. When hot add a touch of olive oil and chopped garlic (If you like the red chile flakes here is where you add it.) When the garlic is soft but nowhere near brown place the clams in the pan and cover. After about a minute throw splash in some white wine and cover again. After another minute you should have open clams and a lot of clam juice in the pan. Remove the clams to a bowl and reduce the heat on the pan.

Look in the pan. This is your sauce. You will soon be placing pasta in this sauce and you want the pasta to be covered but not swimming, so you are adjusting the heat so that it reduces to that target when your timer goes off. Just before it does, swirl in butter to enrich the sauce.

When the timer goes off you have pasta which is not quite cooked. That is what you want. Use tongs and directly lift the pasta out of the boiling water and into the sauce. There is a reason for this. The pasta water has starch in it from the pasta and some of this water will come along with the pasta into the sauce. The starch tastes good and it will help give body to the sauce. Also, the water will increase the volume of the sauce and you want this because you are going to cook the pasta for its remaining minute in the sauce. Pasta is a sponge at this point of the cooking process (think of what your pasta looks like when you have leftovers: swollen and soft. It has soaked up everything around it.) The pasta will soak up the juices in its last minute of cooking. Fresh pasta will not do this.

When this is done, throw in your parsley, toss and plate the pasta. Arrange the clams on top and serve. Provide bread and fork. Beer is best.

Here is a nice article (via The Browser) theorizing about why Wikipedia works. The apparent puzzles are why people contribute to this public good and why it withstands vandalism and subversion. The first puzzle is no longer a puzzle at all, even us economists now accept that people freely give away their information and effort all the time. But no doubt others have just as much motivation, or more, to vandalize and distort, hence the second puzzle.

The article focuses mostly on the incentives to police which is the main reason articles on say, Barack Obama, probably remain neutral and factual most of the time. But Wikipedia would not be important if it were just about focal topics that we already have dozens of other sources on. The real reason Wikipedia is as valuable a resource as it is stems from the 99.999% of articles that are on obscure topics that only Wikipedia covers.

For example, Barbicide.

These articles don’t get enough eyeballs for policing to work, so how does Wikipedia solve puzzle number two in these cases? The answer is simple: a vandal has to know that, say, John I of Trebizond exists to know that there is a page about him on Wikipedia that is waiting there to be vandalized. (I just vandalized it, can you see where?)

There are only two classes of people who know that there exists a John I of Trebizond (up until this moment that is.) Namely, people who know something useful about him and people who want to know something useful about him. So puzzle number 2 is elegantly sidestepped by epistemological constraints.

In chess, one way a game can be declared a draw is if black, say, has no legal move. This is called stalemate. Typically stalemate occurs because white has a material advantage but fails to checkmate and instead leaves the black king with no space to move that does not walk into check. It is illegal to place your own king in check.

The reason stalemate is an artificial rule is that check is an artificial rule. Clearly the object in chess is to conquer the opponent’s king. One can imagine that check evolved as a way to prevent dishonorable defeat when you overlook a threat against your king and allow it to be captured even though it could have escaped. To prevent this, if your king is in check the rules of chess require that you escape from check on the next move and it is illegal to move into check. This rule means that the only way to win is to checkmate: place your opponent in a position where his king is threatened and cannot escape the threat. The game ends there because on the very next move the king will certainly be captured.

This gives rise to stalemate: it is only because of check that a player can have no legal move. If we dispensed with checkmate, replacing it with the more transparent and natural objective of capturing the king, and eliminating the requirement that you cannot end your turn in check, then a player would always have a legal move. (it is easy to prove this.) Thus, no stalemate.

You can learn a lot about who loves you by walking around with food on your face.

Should you tell someone when they have food on their face? You will embarrass them but you will spare them embarrassment later. The embarrassment comes from common knowledge. He knows that you know, etc. that he had food on his face. You would escape this if you could alert him about the food without him knowing it was you.

You could wait and expect that the food will fall. But you run the risk that it won’t and he’ll discover the food and realize that you let him walk around with food on his face. And once you wait for a bit you are committed. You can’t very well tell him after the meal is over. “You mean you sat there talking to me the whole time with sauce on my chin?”

And what happens when you are in a group and one guy has food on his face? Whose going to tell? Whoever is the first to talk proves that everyone else was willing to ignore it.

Bottom line: if you are dining with me and I have food on my face, send me a text message.

Sandeep has previously blogged about the problems with torture as a mechanism for extracting information from the unwilling. As with any incentive mechanism, torture works by promising a reward in exchange for information. In the case of torture, the “reward” is no more torture.

Sandeep focused on one problem with this. This works only if the torturer will actually carry out his promise to stop torturing once the information is given. But once the information is given the torturer now knows he has a real terrorist and in fact a terrorist with valuable information. This will lead to more torture (for more information) not less. Unless the torturers have some way to tie their hands and stop torturing after a few tidbits of information, the captive soon figures out that there is no incentive to talk and stops talking. A well-trained terrorist knows this from the beginning and never talks.

Let me point out yet another problem with torture. This one cannot be solved even by enabling the torturers to commit to an incentive scheme.

The very nature of an incentive scheme is that it treats different people differently. To be effective, torture has to treat the innocent different than the guilty. But not in the way you might guess.

Before we commence torturing we don’t know in advance what information the captive has, and indeed we don’t know for sure that he is a terrorist at all, even though we might be pretty confident. A captive who really has no information at all is not going to talk. Or if he does he is not going to give any valuable information, no matter how much he would like to squeal and stop the torture.

And of course the true terrorist knows that we don’t know for sure that he is a terrorist. He would like to pretend that he has no information in hopes that we will conclude he is innocnent and stop torturing him. Therefore the torture must ensure that the captive, if he is indeed an informed terrorist, won’t get away with this. With torture as the incentive mechanism, the only way to do this is to commit to torture for an unbearably long time if the captive doesn’t talk.

And this leads us to the problem. In the face of this, the truly informed terrorist begins talking right away in order to avoid the torture. The truly innocent captive cannot do that no matter how much he would like to. And so torture, if it is effective at all, necessarily inflicts unbearable suffering on the innocent and very little suffering on the actual terrorists.

De Waal’s own experiments suggest that capuchin monkeys are sensitive to fairness. If another monkey gets a tasty grape, they will not cooperate with an experimenter who offers a piece of cucumber (Nature, vol 425, p 297). A similar aversion has been spotted in dogs (New Scientist, 13 December 2008, p 12), and even rabbits seem affected by inequality, leading de Waal to believe that an ability to detect and react to injustice is common to all social animals. “Getting taken advantage of by others is a major concern in any cooperative system,” he says.

This article mostly just regurtitates some tired and fragile “evolutionary” explanations for fairness and revenge, but there are a few interesting tidbits, like some experiments with monkeys and this joke:

A genie appears to a man and says: “You can have anything you want. The only catch is that I’ll give your neighbour double.” The man says: “Take out one of my eyes.”

Following up on my previous post about the infield fly rule, lets get to the bottom of the zero-sum game that ensues when there is a fly ball in the infield. Let’s suppose the bases are loaded and there are no outs.

The infield fly rule is an artificial rule under which the batter is immediately called out and the runners are free to remain standing on base. Wikipedia recounts the usual rationale:

This rule was introduced in 1895 in response to infielders’ intentionally dropping pop-ups to get multiple outs by forcing out the runners on base, who were pinned near their bases while the ball was in the air.[2] For example, with runners on first and second and fewer than two outs, a pop fly is hit to the third baseman. He intentionally allows the fly ball to drop, picks it up, touches third and then throws to second for a double play. Without the Infield Fly Rule it would be an easy double play because both runners will tag up on their bases expecting the ball to be caught.

I would argue (as do commenters to my previous post) that there is no reason to prevent a double play from this situation, especially because it involves some strategic behavior by the defense and this is to be admired, not forbidden. But aren’t we jumping to conclusions here? Will the runners really just stand there and allow themselves to be doubled-up?

First of all, if there is going to be a double play, the offense can at least ensure that the runners remaining on base will be in scoring position. For example, suppose the runner on second runs to third base and stands there. And the batter runs to first base and stands there. The other runners stay put. Never mind that there will now be two runners standing on first and third base, this is not illegal per se. And in any case, the runner can stop just short of the base poised to step on it safely when the need arises. What can the defense do now?

If the ball is allowed to drop, there will be a force out of the runners on third and first. A double play. But the end result is runners on first and third. Better than runners on first and second which would result if the three runners stayed on their bases. And careful play is required by the defense. If the force is taken first at second base, then this nullifies the force on the remaining runners and the runner on third would be put out only by a run-down, a complicated play that demands execution by the defense. The runner could easily score in this situation.

If on the other hand the ball is caught, then the runer on second will be put out as he is off base. Another double play but again leaving runners on first and third.

So the offense can certainly do better than a simplistic analysis suggests. They could allow the double play but ensure that no matter what the defense does, they will be left with runners on first and third.

But, in fact they can do even better than that. The optimal strategy turns out to be even simpler and avoids the double play altogether. It is based on rule 7.08H: (I am referring to the official rules of Major League Baseball here, especially section 7)

A runner is out when … He passes a preceding runner before such runner is out

According to this rule, the batter can run to first base and stand there. All other base runners stay where they are. Now, a naive analysis suggestst that the fielder can get a triple play by allowing the ball to fall to the ground and using the force play at home, third, and second. But the offense needn’t allow this. The moment the ball touches the ground, the batter can advance toward second base, passing the runner who is standing on first and causing himself, the batter, to be called out. One out, and the only out because according to rule 7.08C, this nullifies the force so that all the baserunners can stay where they are, leaving the bases loaded:

if a following runner is put out on a force play, the force is removed and the runner must be tagged to be put out.

Given this option, the fielder can do no better than catch the ball, leaving the bases loaded. No double play. The same outcome as if the infield fly were called. So the designers of the infield fly rule were game theorists. They figured out what would happen with best play and they just cut to the chase.

But just because best play leads to this outcome doesnt mean that we shouldn’t require the players to play it out. When one team is heavily favored, we don’t call the game for the favorite just because we know that with best play they will win. To quote a famous baseball adage “that’s why they play the game.” The same should be true for infield flies. There’s a lot that both sides could get wrong.

As a final note, let me call your attention to the following, perhaps overlooked but clearly very important rule, rule 7.08I. I don’t think that the strategy I propose runs afoul of this rule, but before using the strategy a team should make certain of this. We cannot make a travesty of our national pastime:

7.08(i) A runner is out when … After he has acquired legal possession of a base, he runs the bases in reverse order for the purpose of confusing the defense or making a travesty of the game. The umpire shall immediately call “Time” and declare the runner out;

The first time I ever flew to Canada, I was flying to Toronto and I forgot to bring my passport. This was pre 9/11 and so the immigration authorities still had a sense of humor. Upon landing they brought me to the basement to interrogate me. Only one question was required and it was ingenious. “What is the infield fly rule?” Only an American would know the answer to this question. (The immigration authorities knew the right trade-off between Type I and Type II errors. A quick survey of my dinner companions tonight revealed that indeed only Americans knew the answer, but not all Americans.)

Suppose there is a runner on first base and the ball is hit in the air where it is catchable by an infielder. As the ball hangs in the air, it sets off a tiny zero sum game-within-the-game to be played by the players on the ground watching it fall to Earth. For if the ball is caught by the infielder, then the runner must be standing on first base, else he will be out after a quick throw to the first baseman, a double play. But, if he does stay standing on first base then the infielder can allow the ball to fall to the ground forcing the runner to advance. Then a quick throw to second base will get the runner out. And again a double play unless the batter has already made it to first.

Apparently this goes against some moral code deeply ingrained in American culture. Is it that the optimal strategy is random? Is it that we don’t want our heroes stranded between bases waiting to see which way they will meet their end? Is it that we don’t want to see the defense gaining advantage by purposefully dropping the ball? Whatever it is, we have ruled it out.

The infield fly rule states that in the above situation, the batter is immediately called out and the runner must stay on first base. No uncertainty, no inscrutability, no randomization. No intrigue. No fun.

But we are game theorists and we can still contemplate what would happen without the infield fly rule. Its actually not so bad for the runner. The runner should stand on first base. Usually by the time the ball descends, the batter will have made it to first base and a double play will be avoided as the infielder can either catch the ball and get the batter out or drop the ball and get the runner out. But not both.

In fact, if the ball is hit very high in the infield (usually the case since an infield fly almost always occurs because of a pop-up) the batter should advance to second base and even to third if he can. That is, run past the base runner, a strategy that otherwise would never be advisable. This forces the infielder to catch the ball as otherwise the best he can do is force out the runner on first, leaving a runner in scoring position.

So in these cases an infield fly does not really introduce any subtle strategy to the game. When the team at-bat plays an optimal strategy, the outcome entails no randomness. The final result is that there will be one out and a runner will remain on first base. And the fielder can always catch the ball to get the out.

However, this is not the only situation where the infield fly rule is in effect. It also applies when there are runners on first and second and also bases loaded. In those situations, if we did away with the infield fly rule the strategy would be a bit more subtle. And interesting! Lets try to figure out what would happen. Post your analysis in the comments.

(conversation with Roberto, Massimo, Itai, Alesandro, Wojciech, Alp, Stefan and Takashi acknowledged)

Next time: eliminating stalemate (another mysterious artificial rule) in Chess.

Update: Ah, a reader points out that the infield fly rule is waived when there is only a runner on first. Good thing my friendly immigration officer didnt know that! (even if he did, he would know that only an American would get the question wrong in that particular way).

In the film A Beautiful Mind about John Nash, there is a scene which purports to dramatize the moment in which Nash developed his idea for Nash equilibrium. He and three mathematician buddies are in a bar (here I might have already jumped to the conclusion that the story is bogus, but I just got back from Princeton and I can confirm that there is a bar there.) There are four brunettes and a blonde and the four mathematicians are scheming about who will go home with the blonde. Nash proposes that the solution to their problem is that none of them go for the blonde.

Let’s go to the video.

Of course this is not a Nash equilibrium (also it is inefficient so it cannot be a dramatization of Nash’s bargaining paper either.) However, this makes it the ideal teaching tool.

- This game has multiple equilibria with different distributional consequences.

- The characters talk before playing so its a good springboard for discussion of how pre-play communication should or should not lead to equilibrium.

- One of the other mathematicians actually reveals that he understands the game better than Nash does when he accuses Nash of trying to send them off course so that Nash can swoop in on the blonde.

- Showing what isn’t a Nash equilibrium is the best way to illustrate what it takes to be a Nash equilibrium.

- It has the requisite sex to make it fun for undergraduates.

You write several novels and transfer copyright to a publisher in exchange for royalty payment. When you die your heirs have a legally granted option to negate the transfer of copyright. This option limits how much your publisher will pay you for the copyright. So you attempt to block your heirs by entering a second contract which pre-emptively regrants the copyright.

Eventually you die and your heirs ask the courts to declare your pre-emptive contract invalid.

You are (or were) John Steinbeck and your case is before the Supreme Court. If I am reading this right the appelate court decision went against the heirs. And remarkably the Songwriter’s Guild of America filed an amicus brief in favor of the heirs. (ascot angle: scotusblog.)

A standard introductory graduate textbook on game theory, A Course in Game Theory by Martin Osborne and Ariel Rubinstein is now freely available in PDF format. You can download it here. This is a great step toward the day when there will be top quality freely available textbooks in all subjects and the day when students and faculty will not be held-up. While we are on the subject, here is a list of other free economics books (right-hand column.)

Hunger strikes seem pointless to a game theorist. You threaten to starve yourself. I laugh and wait around until you give up and start eating again. So why are they so common? One answer might be that they are not common at all and its for that reason that the few hunger strikes that occur get so much media attention. But I think they are more common than my caracicture would allow. For example, there are two big hunger strikes in the news right now. Roxana Sebari, the American journalist imprisoned in Iran was on a hunger strike to draw attention to her captivity. Mia Farrow, the American actress, was on a hunger strike to draw attention to the crisis in Darfur.

Both were called off in the last few days. Do hunger strikes every achieve anything?

I can see one way that a hunger strike can be effective for a prisoner held in a foriegn country. The key idea is that the hunger striker may reach a point where she loses the will/ability to feed herself and then the responsibility shifts entirely on the captors to keep the victim alive. This may require moving the prisoner to a hospital or some other emergency action which will draw the attention of the international community and potentially bring pressure to allow medical attention from doctors in the prisoner’s home country.

And looking forward to this possibility, the captors may make concessions early to a hunger-striker as now both parties would benefit from preventing the strike from reaching that stage.

Update: Roxana Sebari will be freed today. I wonder if the hunger strike played any role. She abandoned it a few days ago and this turn of events today appears to be a total surprise.