You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘game theory’ tag.

We saw The Fantastic Mr Fox a few weeks ago. It was a thoroughly entertaining movie and I highly recommend it. But this is not a movie review. Instead I am thinking about movie previews and why we all subject ourselves to sitting through 10-plus minutes of previews.

The movie is scheduled to start at the top of the hour, but we all know that what really starts at the top of the hour are the previews and they will last around 10 minutes at least. Why don’t we all save ourselves 10 minutes of time and show up 10 minutes late?

Maybe you like to watch previews but I don’t and in any case I can always watch them online if I really want to. I will assume that most people would prefer to see fewer previews than they do.

One answer is that the theater will optimally randomize the length of previews so that we cannot predict precisely the true starting time of the movie. To guarantee that we don’t miss any of the film we will have to take the chance of seeing some previews. But my guess is that this doesn’t go very far as an explanation and anyway the variation in preview lenghts is probably small.

In fact, even if the theater publicized the true start time we would still come early. The reason is that we are playing an all-pay auction bidding with our time for the best seats in the theater. Each of us decides at home how early to arrive trading off the cost of our time versus the probability of getting stuck in the front row. The “winner” of the auction is the person who arrives earliest, the prize is the best seat in the theater, and your bid is how early to arrive. It is “all pay” because even the loser pays his bid (if you come early but not early enough you get a bad seat and waste your time.)

In an all pay auction bidders have to randomize their bids. Because if you knew how everyone else was bidding you would arrive just before them and win. But then they would want to come earlier too, etc. The randomizations are calibrated so that you cannot know for sure when to arrive if you want to get a good seat and the tradeoffs between coming earlier and later are exactly balanced.

As a result most people arrive early, sit and wait. Now the previews come in. Since we are all going to be there anyway, the theater might as well show us previews. Indeed, even people like me would rather watch previews than sit in an empty theater, so the theater is doing us a favor.

And this even explains why theater tickets are always general admission. Let’s compare the alternative. The theater knows we are “buying” our seats with our time. The theater could try to monetize that by charging higher prices for better seats. But it’s a basic principle of advertising that the amount we are willing to pay to avoid being advertised at is smaller than the amount advertisers are willing to pay to advertise to us. (That is why pay TV is practically non-existent.) So there is less money to be made selling us preferred seats than having us pay with our time and eyeballs.

Readers of this blog know that I view that as a very good thing.

Justin Rao from UCSD analyzes shot-making decisions by the Los Angeles Lakers over the course of 60 games in the 2007-2008 NBA season. He collected data on the timing of the shot and identity of the shooter and then recorded additional data such as defensive pressure and shot location by watching the games on video. The data were used to check some basic hypotheses of the decision theory and game theory of shot selection.

The team cooperatively solves an optimal stopping problem in deciding when to take a shot over the course of a 24 second possession. At each moment a shot opportunity is realized and the decision is whether to take that shot or to wait for a possibly better opportunity to arise. Over time the option value of waiting declines because the 24 second clock winds down and the horizon over which further opportunities can appear dwindles. This means that the team becomes less selective over time. As a consequence, we should see in the data that the success rate of shots declines on average later in the possession. Justin verifies this in the data.

Of course, the shot opportunities do not arise exogenously but are the outcome of strategy by the offense and defense. The defense will apply more pressure to better shooters and the offense will have their better shooters take more shots. Both of these reduce the shooting percentage of the better shooters and raise the shooting percentage of the worse shooters. (For example when the better shooter takes more shots he does so by trying to convert less and less promising opportunities.)

With optimal play by both sides, this trend continuues until all shooters are equally productive. That is, conditional on Kobe Bryant taking a shot at a certain moment, the expected number of points scored should be the same as the alternative in which he passes to Vladimir Radmanovic who then shoots. To achieve this, Kobe Bryant shoots more frequently but has a lower average productivity. Also the defense covers Radmanovic more loosely in order to make it relatively more attractive to pass it to him. This is all verified in the data.

Finally, these features imply that a rising tide lifts all boats. That is, when Kobe Bryant is on the court, in order for productivities to be equalized across all players it must be that all other players’ productivities are increased relative to when Kobe is on the bench. He makes his teammates better. This is also in the data.

The equal productivity rule applies only to players who actually shoot. In rare cases it may be impossible to raise the productivity of the supporting cast to match the star’s. In that case the optimal is a corner solution: the star should take all the shots and the defense should guard only him. On March 2, 1962 Wilt Chamberlin was so unstoppable that despite being defended by 3 and sometimes 4 defenders at once, he scored 100 points, the NBA record.

My sketch of the snowball fight reminded Eddie Dekel of a popular children’s game. After he described it to me, I recognized it as a game I have seen my own kids play. It works like this. Two kids face off. At each turn they simultaneously choose one of three actions: load, shoot, defend. (They do this by signaling with their arms: cock your wrist to load, make a gun with your fist to shoot, cross your arms across your chest to defend. They first clap twice to synchronize their choices, just like in rock-paper-scissors.)

If you shoot when the other is loading you win. You cannot shoot unless you have previously loaded. If you shoot unsuccessfully (because the opponent either defended or also shot) your gun is empty and you must reload again. (Your gun holds only one bullet. But Eddie mentioned a variant in which guns have some larger, but still finite, capacity.)

The game goes on until someone wins. In practice it usually ends pretty quick. But what about in theory?

First a little background theory. This is a symmetric, zero-sum, complete information multi-stage game. If we assign a value of 1 to winning and 0 to losing, the symmetric zero-sum nature means that each player can guarantee an expected payoff of 1/2. In that respect the game is similar to rock-scissors-paper. Indeed the game appears to be a sort-of dynamic extension of RSP.

But, despite appearances, it is actually much less interesting than RSP. In RSP, the ex ante symmetry (each player expects a payoff of 1/2) is typically broken ex post (often one player wins and the other loses, although sometimes it is a draw.) By contrast, with best play LSD (load, shoot, defend silly I actually don’t know if it has an official name) is never decisive and in fact it never ends.

Here’s why. The game has four “states” corresponding to how many bullets (zero or one) the two players currently have in their guns. Obviously the game cannot end when the state is (0,0) and since playing load is either forbidden (depending on the local rules) or dominated when the state is (1,1), the game cannot end there either.

So it remains to figure out what best play prescribes when the game is imbalanced, either state (1,0) or (0,1). The key observation is that just as at the beginning of the game, where symmetry implied that each player had an expected payoff of 1/2, it is still true at this state of the game that even the weaker player can guarantee an expected payoff of 1/2. Simply defend. Forever if need be. There is no reason to think that this is an optimal strategy but still its one strategy at your disposal so you certainly can’t do worse than that.

The surprising thing is that best play requires it. To see why, suppose that the weaker player chooses load with positive probability. Then the opponent can play shoot with probality 1 and the outcome is either (shoot, load) [settle down Beavis] in which case the opponent wins, or (shoot, defend) in which case the game transits to state (0,0). Since the value of the first possibility is 1 and the value of the second is 1/2 (just as at the start of the game), this gives an expected payoff to the opponent larger than 1/2. But since payoffs add up to 1, that gives the weaker player an expected payoff less than 1/2 which he would never allow.

So the weaker player must defend with probability 1 and this means that the game will never end. Pretty boring for the players, but rather amusing for the spectators.

We can try to liven it up a bit for all involved. The problem is that its not really like RSP or its 2-action cousin Matching Pennies which work the way they do because of the cyclical relation of their strategies. (Rock beats Scissors which beats Paper which beats Rock…) We can add in an element of that by removing the catch-all defend action and replace it with two actions defend-left and defend-right (say the child leans to either side.) And then instead of plain-old shoot, we have shoot-left and shoot-right. Your shot misses only when you shoot to the opposite side that he leans. There are a number of ways to rule on what happens when I shoot-left and he loads, but I would guess that anything sensible would produce a game that is more interesting than LSD.

The safeguards that are employed in airport security policy are found using the “best response dynamic”: Each player chooses the optimal response to their opponent’s strategy from the last period. So, the T.S.A. best-responds to the shoe bomber Richard Reid and a terrorist plot to blow up planes with liquid explosives. We end up taking our shoes off and having tiny tubes of toothpaste in Ziplock bags. So, a terrorist best-responds by having a small device divided into constituent parts and hidden in his underwear. One part has to be injected into another via a syringe and the complications that ensue prevent the successful detonation of the bomb. In this sense, each player is best-responding to the other and the airport security policy, by making it a bit harder to carry on a complete bomb, succeeded with a huge dose of good luck thrown in.

What should we learn from the newest attempt to blow up an airplane?

First and most obviously, the best way to minimize the impact of terrorism is to stop terrorists before they can even get close to us. This appears to be the main failure of security policy in the recent incident – more focus on intelligence and filtering of watch lists is vital. Second, the best response dynamic should not be the only way to inform policy. There are already rumors that no-one will be allowed to walk around for the last hour of the flight or have personal items on their lap. Terrorists will respond to these policies by blowing up planes earlier in flight. Does that make anyone feel any safer or the terrorists less successful? The main problem is that terrorists are thinking up new schemes to get to nuclear power stations, kidnap Americans abroad and other horrible things that should being brainstormed and pre-empted. The best response dynamic is backward looking and cannot forecast these problems or their solutions. This second point is also obvious. The fact that a boy whose father turned him in got on a plane with a bomb suggests that even obvious points are worth making.

From the fantastic blog, Letters of Note.

Circa 1986, Jeremy Stone (then-President of the Federation of American Scientists) asked Owen Chamberlain to forward to him any ideas he may have which would ‘make useful arms control initiatives’. Chamberlain – a highly intelligent, hugely influential Nobel laureate in physics who discovered the antiproton – responded with the fantastic letter seen below, the contents of which I won’t mention for fear of spoiling your experience. Unfortunately, although I can’t imagine the letter to be anything but satirical, I’m uninformed when it comes to Chamberlain’s sense of humour and have no way of verifying my belief. Even the Bancroft Library labels it as ‘possibly tongue-in-cheek’.

Via The Volokh Conspiracy, I enjoyed this discussion of the NFL instant replay system. A call made on the field can only be overturned if the replay reveals conclusive evidence that the call was in error. Legal scholarship has debated the merits of such a system of appeals relative to the alternative of de novo review: the appelate body considers the case anew and is not bound by the decision below.

If standards of review are essentially a way of allocating decisionmaking authority between trial and appellate courts based on their relative strengths, then it probably makes sense that the former get primary control over factfinding and trial management (i.e., their decisions on those matters are subject only to clear error or abuse of discretion review), while the latter get a fresh crack at purely “legal” issues (i.e., such issues are reviewed de novo). Heightened standards of review apply in areas where trial courts are in the best place to make correct decisions.

These arguments don’t seem to apply to instant replay review. The replay presumably is a better document of the facts than the realtime view of the referee. But not always. Perhaps the argument against in favor of deference to the field judge is that it allows the final verdict to depend on the additional evidence from the replay only when the replay angle is better than that of the referee.

That argument works only if we hold constant the judgment of the referee on the field. The problem is that the deferential system alters his incentives due to the general principle that it is impossible to prove a negative. For example consider the (reviewable) call of whether a player’s knee was down due to contact from an opposing player. Instant replay can prove that the knee was down but it cannot prove the negative that the knee was not down. (There will be some moments when the view is obscured, we cannot be sure that the angle was right, etc.)

Suppose the referee on the field is not sure and thinks that with 50% probability the knee was down. Consider what happens if he calls the runner down by contact. Because it is impossible to prove the negative, the call will almost surely not be overturned and so with 100% probability the verdict will be that he was down (even though that is true with only 50% probability.)

Consider instead what happens if the referee does not blow the whistle and allows the play to proceed. If the call is challenged and the knee was in fact down, then the replay will very likely reveal that. If not, not. The final verdict will be highly correlated with the truth.

So the deferential system means that a field referee who wants the right decision made will strictly prefer a non-call when he is unsure. More generally this means that his threshold for making a definitive call is higher than what it would be in the absence of replay. This probably could be verified with data.

On the other hand, de novo review means that, conditional on review, the call made on the field has no bearing. This means that the referee will always make his decision under the assumption that his decision will be the one enforced. That would ensure he has exactly the right incentives.

Each Christmas my wife attends a party where a bunch of suburban erstwhile party-girls get together and A) drink and B) exchange ornaments. Looking for any excuse to get invited to hang out with a bunch of drunk soccer-moms, every year I express sincere scientific interest in their peculiar mechanism of matching porcelain trinket to plastered Patricia. Alas I am denied access to their data.

So theory will have to do. Here is the game they play. Each dame brings with her an ornament wrapped in a box. The ornaments are placed on a table and the ladies are randomly ordered. The first mover steps to the table, selects an ornament and unboxes it. The next in line has a choice. She can steal the ornament held by her predecessor or she can select a new box and open it. If she steals, then #1 opens another box from the table. This concludes round 2.

Lady #N has a similar choice. She can steal any of the ornaments currently held by Ladies 1 through N-1 or open a new box. Anyone whose ornament is stolen can steal another ornament (she cannot take back the one just taken from her) or return to the table. Round N ends when someone chooses to take a new box rather than steal.

The game continues until all of the boxes have been taken from the table. There is one special rule: if someone steals the same ornament on 3 different occasions (because it has been stolen from her in the interim) then she keeps that ornament and leaves the market (to devote her full attention to the eggnogg.)

Theoretical questions:

- Does this mechanism produce a Pareto efficient allocation?

- Since this is a perfect-information game (with chance moves) it can be solved by backward induction. What is the optimal strategy?

- How can this possibly be more fun than quarters?

Auction sites are popping up all over the place with new ideas about how to attract bidders with the appearance of huge bargains. The latest format I have discovered is the “lowest unique bid” auction. It works like this. A car is on the auction block. Bidders can submit as many bids as they wish ranging from one penny possibly to some upper bound, in penny increments. The bids are sealed until the auction is over. The winning bid is the lowest among all unique bids. That is, if you bid 2 cents and nobody else bids 2 cents, but more than one person bid 1 cent, then you win the car for 2 cents.

In some cases you pay for each bid but in some cases bids are free and you pay only if you win. Here is a site with free bidding. An iPod shuffle sold for $0.04. Here is a site where you pay to bid. The top item up for sale is a new house. In that auction you pay ~$7 per bid and you are not allowed to bid more than $2,000. A house for no more than $2,000, what a deal!

I suppose the principle here is that people are attracted by these extreme bargains and ignore the rest of the distribution. So you want to find a format which has a high frequency of low winning bids. On this dimesion the lowest unique bid seems even better than penny auctions.

Caubeen curl: Antonio Merlo.

After a day of conference talks, but before drinks arrive, game theorists have been known to debate whether what is known as Zermelo’s theorem was actually proved by Zermelo. Eran Shmaya (who is always fun to talk to with or without drinks) decided to go and look at the paper (recently translated) and all but strips Zermelo of his theorem.

So, Zermelo clearly did not set out to prove his eponymous theorem. But was he aware of it ? I guess the answer depends on what you mean by being aware of a mathematical statement (were you aware of the fact that any even number greater than 2 can be written as a sum of a prime number and an even number before you read this sentence ?). But I do believe that some of the logical implications in Zermelo’s paper only make sense if you already assume his theorem.

Via kottke, Clusterflock gives five simple rules for effective bidding on eBay:

Step One:Find the product you want.

Step Two:

Save the product to your watch list.

Step Three:

Wait.

Step Four:

Just before the item ends, enter the maximum amount you are willing to pay for the item.

Step Five:

Click submit.

This is called sniping. That’s a pejorative label for what is actually a sensible and perfectly straightforward way to bid. eBay is essentially an open second-price auction and sniping is a way to submit a “sealed” bid. It’s a popular strategy and advocated by many eBay “experts.” But does it really pay off?

Tanjim Hossain and I did an experiment (ungated version.) We compared sniping to another straightforward strategy we call squatting. As the name suggests, squatting means bidding your value on an object at the very first opportunity, essentially staking a claim on that object. We bid on DVDs and randomly divided auctions into two groups, sniping on the auctions in the first group and squatting on the other.

The two strategies were almost indistinguishable in terms of their payoff. But for an interesting reason. A lot of eBay bidders use a strategy of incremental bidding. That’s where you act as if you are involved in an ascending auction (like an English auction) and you bid the minimum amount needed to become the high biddder. Once you are the high bidder you stop there and wait to see if you are outbid, then you raise your bid again. You do this until either you win or the price goes above the maximum amount you are willing to pay.

Against incremental bidders, sniping has a benefit and a cost (relative to squatting.) You benefit when incremental bidders stop at a price below their value. You swoop in at the end, the incremental bidders have no time to respond, and you win at the low price.

The cost has to do with competition across auctions for similar objects. If I squat on auction A and you are sniping in auction B, our opponents think there is one fewer competitor in auction B and more opponents enter auction B than A. This tends to raise the price in your auction relative to mine. In other words, squatting scares opponents away, sniping does not.

We found that these two effects almost exactly canceled each other out for auctions of DVDs. We expect that this would be true for similar objects that are homogeneous and sold in many simultaneous auctions. So the next time you are bidding in such an auction, don’t think too hard and just bid your value.

Now, I am still trying to figure out what I am going to do with all these copies of 50 First Dates we won in the experiment.

Steven Landsburg set 10 questions for honors graduates at Oberlin College. #8 is a great undergraduate game theory exercise:

Question 8. The five Dukes of Earl are scheduled to arrive at the royal palace on each of the first five days of May. Duke One is scheduled to arrive on the first day of May, Duke Two on the second, etc. Each Duke, upon arrival, can either kill the king or support the king. If he kills the king, he takes the king’s place, becomes the new king, and awaits the next Duke’s arrival. If he supports the king, all subsequent Dukes cancel their visits. A Duke’s first priority is to remain alive, and his second priority is to become king. Who is king on May 6?

visor volley: BoingBoing.

One of the least enjoyable tasks of a journal editor is to nag referees to send reports. Many things have been tried to induce timeliness and responsiveness. We give deadlines. We allow referees to specify their own deadlines. We use automated nag-mails. We even allow referees to opt-in to automated nag-mails (they do and then still ignore them.)

When time has dragged on and a referee is not responding it is typical to send a message saying something like “please let me know if you still plan to provide a report, otherwise i will try to do without it.” These are usually ignored.

A few years ago I tried something new and every time since then it has gotten an almost immediate response, even from referees who have ignored multiple previous nudges. I have suggested it to other editors I know and it works for them too. I have an intuition for why it works (and that’s why I tried it in the first place) but I can’t quite articulate it, perhaps you have ideas. Here is the clinching message:

Dear X

I would like to respond soon to the authors but it would help me a lot if I could have your report. I realize that you are very busy, so if you think you will be able to send me a report within the next week, then please let me know. If you don’t think you will be able to send a report, then there is no need to respond to this message.

Why is blackmail illegal? Sure it’s mean and all but what makes it a crime? This article raises some questions about the legal scholarship behind blackmail. (The background is the Letterman case.)

Whether or not this is how Hollywood really works, Shargel does have a point of logic. The reasoning that makes blackmail illegal–and a great many other similar business activities not illegal — is something that’s never been satisfactorily explained by legal scholars. It remains a paradox of the law. That said, Halderman and Shargel shouldn’t hold their breath until January, when a judge will rule on their motion to dismiss. Even if it makes no sense, blackmail remains a serious crime.

What about the economics of blackmail? There is one obvious economic rationale for making blackmail a crime: rent-seeking. Seeking out and producing incriminating evidence for the express purpose of ultimately keeping it secret is a waste of labor resources and should be discouraged. And this idea explains an otherwise puzzling asymmetry. That is, presumably I can legally accept payment in return for publicizing good information about you. That is tantamount to threatening not to publicize it if you don’t pay me. Whether I threaten withold good information about you or actively publicize bad information about you I am arguably doing the same thing: threatening to lower your reputation relative to what it would otherwise be.

The economic difference is that allowing blackmail leads to unproductive rent-seeking whereas allowing me to charge you for good publicity incentivizes productive information-gathering.

In rare cases blackmail is efficient. If I want you to dig up the dirt on me (perhaps to keep it out of more dangerous hands) we have an incentive problem. I can’t pay you up front because then you have no incentive to do the search. You will come back claiming that my record is so clean that despite all your efforts you came up empty-handed. Instead I would like to pay you ex post in return for the documents. But once you’ve already sunk the cost of searching, I will hold you up and try to renegotiate the fee. The information is not worth anything to you since blackmail is illegal. We would both prefer to allow you to blackmail me ex post. That way I am effectively commited to pay you for your service and you will work hard.

You can trust me to pay you for the information but now the problem is that I can’t trust you. You will show me only half of what you found and blackmail me to keep that a secret. Once you have your money you will show me the other half and blackmail me again. Forseeing this I won’t pay you the first time.

Once you think of this its hard to see how blackmail works at all and why we need to even make it illegal. The blackmailer has to somehow prove that he is not hiding any additional information. That is probably impossible because any incriminating evidence can be copied.

Maybe the problem can be solved with a reciprocal arrangement. You dig up some dirt on me and yourself. Then you offer me the following deal. I pay you the hush money and you hand over the information about you. I will pay you because in return I get a threat against you which deters you from blackmailing me again.

“You’re a cad if you break up around Christmas. And then there’s New Year’s — and you can’t dump somebody right around New Year’s. After that, if you don’t jump on it, is Valentine’s Day,” Savage says. “God forbid if their birthday should fall somewhere between November and February — then you’re really stuck.

“Thanksgiving is really when you have to pull the trigger if you’re not willing to tough it out through February.”

That’s from a story I heard on NPR about turkey dropping: the spike in break-ups at Thanksgiving followed by a steady period (for the surviving pairs) through the Winter months. If there is a social stigma against cutting it off between Thanksgiving and Valentine’s Day, then there may be value in that. Often social rules emerge arbitrarily but persist only if they serve a purpose, even if that purpose is unrelated to the spirit of the social norm. The post-turkey taboo plays the role of a temporary commitment that can strengthen those relationships that are still worth maintaining.

The value of a relationship fluctuates over time. Not just the total value of the partnership relative to autarky but also the value to the individual of remaining committed. The strength of a relationship is precisely measured by the maximum temptation each partner is willing to forego to keep it alive. The moment a jucier temptation appears, the relationship is doomed.

Unless there is commitment. Commitment is a way of pooling incentive constraints. A relationship becomes stronger if each partner can somehow commit in advance to resist all temptations that will arise over the length of the commitment. This transforms your obligation. Now the strength of the relationship is equal to the expected temptation rather than the most severe temptation actually realized. A social stigma against ending the relationship over certain intervals of time aids such a commitment.

Its good that commitments are temporary, but you want their beginning and end dates to be arbitrary, or at least independent of the arrival process of temptations. The total value of the relationship also fluctuates and you want the freedom to end the relationship when it begins to lag the value of being single. This is especially true in the early stages when there is still a lot to learn about the match. Over time when the value of the relationship has clarified, the length of commitment intervals should increase.

Commitments can also solve an unraveling problem. If you know that your partner will succumb to a juciy temptation and you know that its just a matter of time before a juicy temptation arrives, you become willing to give over to a just-a-little-juicy temptation. Knowing this, she is poised to give it up for just about anything. The commitment short-circuits this at the first step.

Mind Your Decisions looks at the game theory of the classic Thanksgiving showdown between Lucy and Charlie Brown.

Time after time, Lucy would bring her football to the park and entice Charlie Brown to practice some place kicks. Lucy would hold the ball, Charlie Brown would run full-steam to kick it only to have Lucy snatch the ball away at the last minute sending Charlie Brown flying, yelling ARRRRGGGHHH and landing in a heap. What a blockhead. Sure you can understand his willingness to trust her the first time, maybe even the first two times, but after that it’s pretty clear what Lucy’s objective is.

You may try to make excuses for Charlie Brown by arguing that subgame-perfection requires a great deal of strategic sophistication. But you don’t need to invoke any refinements here. The unique Nash equilibrium action for Charlie Brown is to say no. Even worse, not yanking the ball is a weakly dominated strategy for Lucy and after that strategy is eliminated, Charlie Brown has a strongly dominant strategy to walk away.

So it is not surprising that in It’s The Great Pumpkin Charlie Brown, he has finally figured this out and flatly refuses to play Lucy’s game. That’s when she goes contract theory on him.

Now we are reaching higher-order blockheadness. First of all, whether or not the contract is valid, its terms are not verifiable to a court. And Charlie Brown should be able to figure out there is something fishy about this contract. Lucy would only offer a contract if she preferred the outcome (run, don’t yank) to the outcome (walk away). But even though Lucy has never directly revealed any preference between these two outcomes, there is pretty good evidence that the worst possible outcome for Lucy would be to see Charlie Brown successfully kick.

Indeed, Lucy knew from the beginning that Charlie Brown would eventually figure out her intention to yank the ball. After that, she knows Charlie Brown will refuse to play. So if Lucy really preferred (run, don’t yank) to (walk away) then she would prevent this evaporation of trust by allowing Charlie Brown to kick the ball at least a few times, but she never did.

The only way to rationalize Lucy’s steadfast insistence on sending him flying is to assume either that (run, don’t yank) is her least-preferred outcome, or that she thinks that Charlie Brown is indeed a blockhead and unable to deduce her intentions. In either case, Charlie Brown should have viewed Lucy’s contract with deep suspicion.

Cute video from Tim Harford on the information economics of office politics.

(My theory is that in fact the managers will get stuck with cleaning coffee pots. The wage-earners are already held to reservation utility while the managers are likely earning rents. And, as illustrated in the video’s epilogue, there is no fully separating equilibrium in the “threaten to resign” game.)

You are playing in you local club golf tournament, getting ready to tee off and there is last-minute addition to the field… Tiger Woods. Will you play better or worse?

The theory of tournaments is an application of game theory used to study how workers respond when you make them compete with one another. Professional sports are ideal natural laboratories where tournament theory can be tested. An intuitive idea is that if two contestants are unequal in ability but the tournament treats them equally, then both contestants should perform poorly (relative to the case when each is competing with a similarly-abled opponent.) The stronger player is very likely to win so the weaker player conserves his effort which in turn enables the stronger player to conserve his effort and still win.

There is a paper by Kellogg professor Jennifer Brown that examines this effect in professional golf tournaments. She compares how the average competitor performs when Tiger Woods is in the tournament relative to when he is not. Controlling for a variety of factors, Tiger Woods’ presence increases (i.e. worsens, remember this is golf) the score of the average golfer, even in the first round of the tournament.

There are actually two reasons why this should be true. First is the direct incentive effect mentioned above. The other is that lesser golfers should take more risks when they are facing tougher competition. Surprisingly, this is not evident in the data. (I take this to be bad news for the theory, but the paper doesn’t draw this conclusion.)

Also, since golf is a competition among many players and there are prizes for second, third etc., the theory does not necessarily imply a Tiger Woods effect. For example, consider the second-best player. For her, what matters is the drop-off in rewards as a player falls from first to second relative to second to third. If the latter is the steeper fall, then Tiger Woods’ presence makes her work harder. Since the paper looks at the average player, then what should matter is something like concavity vs. convexity of the prize schedule.

Also, remember the hypothesis is that both players phone it in. Unfortunately we don’t have a good control for this because we can’t make Tiger Woods play against himself. Perhaps the implied empirical hypothesis says something about the relative variance in the level of play. When Tiger Woods is having a bad season, competition is tighter and that makes him work harder, blunting the effect of the downturn. When he is having a good season, he slacks off again blunting the effect of the boom. By contrast, for the weaker player the incentive effects make his effort pro-cyclical, amplifying temporal variations in ability.

Jonah Lehrer (to whom my fedora is flipped) prefers a psychological explanation.

News Corp., parent company of Fox News is reported to have made an offer for NBC Universal in competition with Comcast. Who should be willing to pay more for an upstream supplier (NBC), the downstream monopolist (Comcast), or an upstream competitor (News Corp.)?

There were no fire engines, horse-drawn or otherwise. The citizens were the fire department. Each house had its own firebuckets and in the event of a fire, everyone was meant to pitch in. That meant taking your firebucket and joining the line of people from the water tank to the fire.

Does the story so far give you a warm, fuzzy feeling? Friendly folk working together, helping each other out and living by the Kantian categorical imperative. Let me rain on your parade – I am an economist after all. The private provision of public goods is subject to a free-rider problem: The costs of helping someone else outweigh the direct benefits to me so I don’t do it. Everyone reasons the same way so we get the good old Prisoner’s Dilemma and a collectively worse equilibrium outcome.

People have to come up with some other mechanism to mitigate these incentives. In Concord, they chose a contractual solution. Each fire-bucket had the owner’s name and address on it. If any were missing from the fire, you could identify the free-rider and they were fined.

This is the story we got from the excellent tour guide at the Old Manse house in Concord. Home to William Emerson, rented by Nathaniel Hawthorne and overlooking the North Bridge, the location of the first battle of the American Revolution. (We were carefully told that earlier that same historic day in Lexington, although the Redcoats fired, the Minutemen did not fire back so that was not a real battle.) The house has the old firebuckets hanging up by the staircase.

Karthik Shashidar writes to us:

I am a regular reader of your blog, and like most of the stuff that you guys put there. Yesterday while blogging, I came across something which I thought might interest you people, hence I’m writing to you.

Recently my girlfriend and I realized that we were spending way too much time talking to and thinking about each other, and that we needed to scale down in order to give us time to do other things that we want to do. Both of us are in extremely busy jobs and hence time available for other things (including each other) is very limited, and hence the need to scale down.

I was wondering why this is not a widespread phenomenon and why more couples don’t do this “scaling down”

His analysis is here.

There is a natural force pushing couples toward too much engagement. Unilateral escalations make your partner feel good. Even if you internalize the long-run cost due to the inevitable following-suit, the slightest bit of discounting means that the equilibrium level will be above the social optimum. The usual dynamic game logic seems especially perverse here. If I am extra sweet to my sweet does she punish me for that? And what form does the punishment take, even further escalation?

Negotiating down from these heights is indeed tricky. Unilateral de-escalation is risky as Karthik discusses on his blog. The proposal could easily be read as a cold shoulder. Even assuming that both agree to scale down, how do you decide where to go? It is not easy to describe in words a precise level of interaction and this ambiguity leads to the potential for hurt feelings, if there is mis-coordination.

Some dimensions are easier to contract on. It’s easy to commit to go out only on Tuesday nights. However, text messages are impossible to count and the distortions due to overcompensation on these slippery-slope dimensions may turn out even worse than the original state of affairs.

But even setting aside all of these problems, what mechanism can you use to coordinate on a lower scale? If we both make offers and split-the-difference, then the one asking for a higher scale is going to feel hurt. Any mechanism has got to be noisy enough to hide such inequities without being totally random. The trick may be to short-circuit common knowledge. For example we could have a third party make a take-it-or-leave-it proposal and then the two partners secretly reject (if too low) or accept (if not.) The proposal is enacted only if both accept.

This ensures that when the offer is accepted, both parties learn only that each was willing to scale down to at least the same level. And when the offer is rejected, the one who was not willing to go that low will never know whether the other was, i.e. no hurt feelings.

(dinner conversation with Utku, Samson, and Hideo.)

Computer scientists study game theory from the perspective of computability.

Daskalakis, working with Christos Papadimitriou of the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Liverpool’s Paul Goldberg, has shown that for some games, the Nash equilibrium is so hard to calculate that all the computers in the world couldn’t find it in the lifetime of the universe. And in those cases, Daskalakis believes, human beings playing the game probably haven’t found it either.

Solving the n-body problem is beyond the capabilities of the world’s smartest mathematicians. How do those rocks-for-brains planets manage to do pull it off?

Big events at Northwestern this weekend, including Paul Milgrom’s Nemmers’ Prize lecture and a conference in his honor. (My relative status was microscopic.) A major theme of the conference was market design and I heard a story repeated a few times by participants connected with research and implementation of online ad auctions.

Ads served by Yahoo!, Google and others are sold to advertisers using auctions. These auctions are run at very high frequencies. Advertisers bid for space on specific pages at specific times and served to users which are carefully profiled by their search behavior. This enables advertisers to target users by location, revealed interests, and other characteristics.

Not content with these instruments, McDonalds is alleged to have proposed to Yahoo! a unique way to target their ads and their proposal has come to be known as The Happy Contract. Instead of linking their bids to personal profiles of users, they asked to link their bids to weather reports. McDonalds would bid for ad space only when and where the sun was shining. That way sunshine-induced good moods would be associated with impressions of Big Macs, and (here’s the winner’s curse) the foul-weather moods would get lumped with the Whopper.

He is a political scientist at NYU who uses spreadsheets to predict how conflicts will be resolved. He consults for the CIA, earns $50,000 per prediction, and uses his brand of game theory to offer wisdom on questions like “How fully will France participate in the Strategic Defense Initiative?” and “What policy will Beijing adopt toward Taiwan’s role in the Asian Development Bank?”

To predict how leaders will behave in a conflict, Bueno de Mesquita starts with a specific prediction he wants to make, then interviews four or five experts who know the situation well. He identifies the stakeholders who will exert pressure on the outcome (typically 20 or 30 players) and gets the experts to assign values to the stakeholders in four categories: What outcome do the players want? How hard will they work to get it? How much clout can they exert on others? How firm is their resolve? Each value is expressed as a number on its own arbitrary scale, like 0 to 200. (Sometimes Bueno de Mesquita skips the experts, simply reads newspaper and journal articles and generates his own list of players and numbers.) For example, in the case of Iran’s bomb, Bueno de Mesquita set Ahmadinejad’s preferred outcome at 180 and, on a scale of 0 to 100, his desire to get it at 90, his power at 5 and his resolve at 90.

His model is a secret but it seems to be some kind of dynamic coalition formation model. He has predicted that Iran will not obtain a nuclear weapon owing to the rising power of dissident coalitions. In August,

He spent that morning looking over his Iranian data, and he generated a new chart predicting how the dissidents’ power would grow over the next few months. In terms of power, one category — students — would surpass Ahmadinejad during the summer, and by September or October their clout would rival that of Khamenei, the supreme leader. “And that’s huge!” Bueno de Mesquita said excitedly. “If that’s right, it’s huge!” He said he believed that Iran’s domestic politics would remain quiet over the summer, then he thought they’d “really perk up again” by the fall.

A long profile appeared in The New York Times Magazine.

You are attending a conference or other event which brings together a large group of people vaguely acquainted but not tightly connected. There is a dinner where there are many tables seating 6-8 people each. There is no assigned seating. Assuming you care about whom you will sit with, what is your strategy for finding a place to sit?

- To the extent possible, the high-status people will contract early and grab a table to themselves. This is usually possible because in groups like this it is the high-status people who are most likely to know each other well.

- Low-status people often prefer to sit with higher-status people, so they tend to play the waiting game and hop in on a table with some open seats. This usually turns out to be a bad idea (dull and awkward conversation) but it takes a few bad experiences to figure this out. By that time the lesson is irrelevant because your status has improved.

- Middle-status people have learned to care less about the status of those they dine with. And they are not yet so visible that everyone wants to sit with them just out of status-mongering. So their optimal strategy is to move early and find an empty table and sit there. They will be joined by people who are really interested in them and those are the people you want to sit with.

- The latter is generally my strategy. However, usually people don’t want to sit with me. Consistent with the logic of the strategy, this is optimal when it happens.

- There is must be something unique about weddings because there is almost always assigned seating.

- The closer people are to being total strangers the stricter the status ranking becomes, in my experience. Without anything to go on, it boils down to attractiveness. A strict, linear status ranking leads to unraveling as everyone waits to join the best table. This is when assigned seating is necessary. But I don’t think this explains weddings.

The question is ripe for experimental research.

Despite my vast legion of Twitter followers, every one of my attempts to start a new trending topic has failed to catch on. Now I think I understand why.

Suppose that your goal is to coordinate attention on a topic that seems to be on a lot of minds. Attention is a scarce resource and you have only a limited number of topics you can highlight. But suppose, as with Twitter, you see what everyone is talking about. How do you decide which topics to point to?

You probably shouldn’t just count the total number of people talking on a given subject, counting everyone equally. You might think that you would instead give extra weight to the few people that everyone is listening to. Because whatever they say is more likely to be interesting to many, and will soon be on many minds. On Twitter, those would be the people with the most followers. But there is a strong case for doing the opposite and giving extra weight to people with few followers, especially people who are relatively isolated in the social network. This is not out of fairness (or pity) but actually as the efficient way to use your scarce resource.

Efficient coordination means making information public so that not just everyone knows it, but everyone knows that everyone knows it (etc.) If we all have to choose simultaneously what to focus our attention on and we want to be part of the larger conversation, then it matters what we think others are going to focus their attention on. Coordinating attention thus requires making it public what people are talking about.

Suppose we have two topics that are getting a lot of attention, but topic A is being discussed by well-connected individuals and topic B is being discussed more by a diverse group of isolated individuals. Topic A is already public because when you see it discussed by a central figure you know that all other of her followers are seeing it to. Topic B therefore has more to gain from elevating it to the status of trending topic, which immediately makes it public.

I always knew that my Twitter followers were among the wisest. Now I see the true depth of their wisdom. By adding to my follower numbers, they reduce the weight of my comments in the optimal weighting scheme thus ensuring that the crazy things I say will be ingored by the larger network. Join the cause.

We all know about generic drugs and their brand-name counterparts. The identical chemical with two different prices. Health insurance companies try to keep costs down by incentivizing patients to choose generics. You have a larger co-pay when you buy the name brand. Except when you don’t:

Serra, a paralegal, went to his doctor a few months ago for help with acne. She prescribed Solodyn. Serra told her he’d previously taken a generic drug called minocycline that worked well. The doctor told him that the two compounds are basically the same, but that you have to take the generic version in the morning and the evening. With Solodyn, you take one dose a day.

Serra told her that if the name-brand medicine was going to cost a lot more, he’d prefer the generic. “And then she presented this card,” he says. She explained that it was a coupon, and that he should give it to the pharmacist for a break on his insurance copay.

Without the card, Serra’s copay would have been $154.28. But when he got to the pharmacy, he presented his card. “They went to ring it up at the register,” he remembers. “And when it came up, the price was $10.”

NPR has the story. Chupulla chuck: Mike Whinston.

Swoopo.com has been called “the crack cocaine of auction sites.” Numerous bloggers have commented on its “penny auction” format wherein each successive bid has an immediate cost to the bidder (whether or not that bidder is the eventual winner) and also raises the final price by a penny. The anecdotal evidence is that, while sometimes auctions close at bargain prices, often the total cost to the winning bidder far exceeds the market price of the good up for sale. The usual diagnosis is that Swoopo bidders fall prey to sunk-cost fallacies: they keep bidding in a misguided attempt to recoup their (sunk) losses.

Do the high prices necessarily mean that penny auctions are a bad deal? And do the outcomes necessarily reveal that Swoopo bidders are irrational in some way? Toomas Hinnosaar has done an equilibrium analysis of penny auctions and related formats and he has shown that the huge volatility in prices is in fact implied by fully rational bidders who are not prone to any sunk-cost fallacy. In fact, it is precisely the sunk nature of swoopo bidding costs that leads a rational bidder to ignore them and to continue bidding if there remains a good chance of winning.

This effect is most dramatic in “free” auctions where the final price of the good is fixed (say at zero, why not?) Then bidding resembles a pure war of attrition: every bid costs a penny and whoever is the last standing gets the good for free. Losers go home with many fewer pennies. (By contrast to a war of attrition, you can sit on the sidelines as long as you want and jump in on the bidding at any time.) Toomas shows that when rational bidders bid according to equilibrium strategies in free auctions, the auction ends with positive probability at any point between zero bids and infinitely many bids.

So the volatility is exactly what you would expect from fully rational bidders. However, Toomas shows that there is a smoking gun in the data that shows that real-world swoopo bidders are not the fully rational players in his model. In any equilibrium, sellers cannot be making positive profits otherwise bidders are making losses on average. Rational bidders would not enter a competition which gives them losses on average.

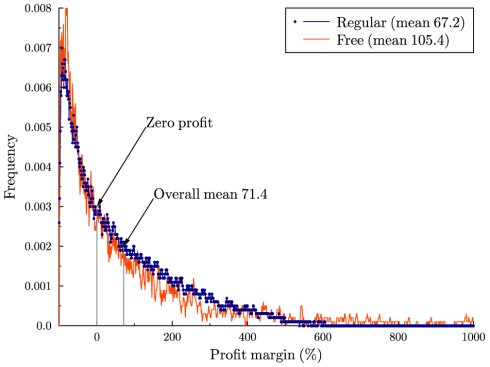

In the following graph you will see the actual distribution of seller profits from penny auctions and free auctions. The volatility matches the model very well but the average profit margin (as a percentage of the object’s value) is clearly positive in both cases. This could not happen in equilibrium.

I heard an interview with Reggie Jackson and Bob Gibson (former baseball greats) on NPR’s Fresh Air this weekend. They spent a lot of time talking about pitching inside and “brushing back” hitters. Reggie Jackson, a hitter, conceded that these were “part of the game.”

There is a mundane sense in which this is true, namely that not even the best pitcher has flawless control and sometimes batters get hit. But Reggie was even talking about intentional beanballs. In what sense is this part of the game?

The penalty for throwing inside is that, if you hit the batter, he gets a free base. (And your teammate might get beaned at the next opportunity.) The problem is that this penalty trigger is partly controlled by the opposition. Other things equal it gives the batter an incentive to stand a bit closer to the plate. In order to discourage this, the pitcher must establish a reputation for throwing inside when a batter crowds the plate. In that sense, intentionally throwing at the hitter is unavoidable strategy, part of the game.

So, one way to short-circuit this effect is to change the condition for giving a free base to something that is exogenous, i.e. independent of any choice made by the batter. For example, the batter gets a free base any time the ball sails more than some fixed distance inside of the plate, whether or not it actually hits the batter. Modern technology could certainly detect this with minimal error.

Whatever the merits of the claims made about Fox News by Obama’s communications team, it can be good strategy to pick a fight with your critics. To the very long list of reasons, add this one. If you can make them so angry that they lose the will to say anything at all nice about you, then you have won a major victory. For then they will have lost all (remaining) credibility.

Not game theory, but research about and even within games. Hit or miss:

One of the most high-profile projects (and most obvious recent failures) was Indiana University’s Arden: The World Of William Shakespeare, which reportedly had a grant of $250,000. It was an experimental MMO which came about via the work of Professor Ed Castronova, author of Synthetic Worlds. Castronova wondered whether the creation of a genuinely educational MMO was possible, and set up the student development project to find out. Having spent thousands of dollars on Arden it was shut down. Castronova cited “a lack of fun”.

via BoingBoing.