You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘economics’ category.

My family have decided that I am too sarcastic. I concurred. So, I agreed to sign an anti-sarcasm contract :

“Under pain of having to donate $1 toward Lego for every infraction, I hereby declare my intention to eschew sarcasm.”

The kids were making $8/day for the first few days till I learned a little self-control. So far so good.

Then, weird little things started happening. A child would ask innocently: “Can we have second dessert?” Or “Can I skip homework today?” etc. I would unfortunately respond with sarcasm.

I realized that the attempt to deal with my sarcasm by giving me incentives had created another incentive problem. I tried to change the contract so the money goes to charity but my kids refused to renegotiate….Is there some corollary of the Holmstrom moral hazard in teams model that says our it is impossible to implement optimal incentives with budget balance?

From a NYT Q&A about a trip to Bangladesh:

WASSIM RAGAB: How do you overcome the corruption in Bangladesh and still run successful projects?

MELINDA: It’s unfortunate and true that Bangladesh is perceived to be one of the world’s most corrupt countries. The Bangladeshis I have met have told me that they feel this in small ways on a fairly regular basis. Because the problem is systemic, it’s hard for them to go against the tide. One doctor I met with yesterday told me that nobody pays attention to traffic lights since you can buy your way out of a ticket for a small fee and because if you don’t run the red light, “everyone else will and you’ll never get to your destination.” Obviously, these unnecessary surcharges on everyday life and other forms of corruption are a major impediment to faster economic growth and it’s something the government and others must address.

Because everyone else is running a red light, a best response is to run it yourself. For some people, a best response to everyone not running the red light is to not run it yourself. This is a coördination game logic. Actions are strategic complements: I am more willing to run the red light if you are running it.

Corruption can be thought of in two ways. First, it is a sunspot that makes the running lights equilibrium focal. Second, there are heterogeneous costs (or benefits) to running a red light. Suppose there is no corruption. Then, there is a threshold equilibrium where people run the red light if and only if their cost is below the threshold. Corruption lowers the costs of running the right and shifts the threshold up: More people run red lights. By strategic complements this creates a spiral where yet more people run red lights etc.

Via WSJ:

The White House’s top economist on Thursday said income inequality in the U.S. has reached the point where the “middle class has shrunk.” He said the development was “causing an unhealthy division in opportunities, and is a threat to our economic growth,” according to prepared remarks…

The consequence of a shrinking middle class, Mr. Krueger said, was “more families falling into either end of the distribution, and fewer in the middle. The statistical word for this is ‘kurtosis.’ I can see why the term polarization has caught on.”

You are managing a small team. You are meant to make sure they work hard. Monitoring is costly and you would like to shirk your responsibilities. But your monitoring is observable to the worker bees. They incur no costs to observe your effort. If you shirk your duties, there will be payback from the workers. There is always the possibility that they turn you in to your supervisor. This could be a deliberate act. More likely, it is inadvertent because “loose lips” that sink ships. So, you are left with no choice but to monitor. And since you are monitoring, the workers are left with no option but to work. Everyone is worse off. If only the workers could keep their mouths shut and the manager could shirk.

Yoram Bauman is also an environmental economist. With this hat on, in the NYT, he says:

Learning about the shortcomings as well as the successes of free markets is at the heart of any good economics education, and students — especially those who are not destined to major in the field — deserve to hear both sides of the story.

Which reminds me of my plan to put in more stuff about common property resources, public goods and externalities into my MBA course next quarter…

On the importance of collateral:

[E]very businessman knows leverage is important. Even Shakespeare

understood that collateral is more important than the interest rate. Who here

can remember the interest rate Shylock charges Antonio in the Merchant of

Venice? But all of you remember the pound of flesh collateral.

On debt forgiveness:

Imagine a $160,000 loan on a house that is now worth $100,000. Lenders on average get less than

25% of the loan back when a subprime borrower is thrown out of his home,

meaning in this case the lender can expect $40,000. Why? Because it takes years

to throw the family out of the house, during which time the owner does not pay

his taxes or his mortgage, and the house is ruined. If the loan had been written

down to $80,000 the borrower might well have paid all $80,000 back, perhaps by

selling the house, because then there would be $20,000 in it for him. By

demanding everything and then throwing the borrower out when he refuses, the

lender loses even more. As Portia says in very similar circumstances in the

Merchant of Venice “The Quality of mercy is not strained …It helpeth him who

gives and him who takes.” The most catastrophic blunder the American

administration has made is in not coordinating a forgiveness on mortgage loans

by lenders.

Richard Russo bemoans Amazon’s takeover of retail:

Amazon was encouraging customers to go into brick-and-mortar bookstores on Saturday, and use its price-check app (which allows shoppers in physical stores to see, by scanning a bar code, if they can get a better price online) to earn a 5 percent credit on Amazon purchases (up to $5 per item, and up to three items).

Amazon seems to be using decentralized market intelligence to undercut the competition. Good for consumers but bad for bricks-and-mortar retailers, as Richard Russo explains. But the logic can equally go the other way. Firms can use market intelligence to maintain high prices. If Firm A can immediately observes Firm B’s price cut (and vice versa), it can match the price cut immediately. This can eliminate the incentive to cut prices and hence allow firms to maintain high prices. A local example:

Over a four-year period beginning in the summer of 1996, the two dominant supermarket chains in the Chicago area charged virtually identical prices for milk, attorneys in a class-action lawsuit accusing Jewel and Dominick’s of price-fixing charged Friday in opening arguments.

So closely aligned were the chains’ pricing structures for the staple that whenever one changed milk prices the other would match it within days, the attorneys alleged….

For example, he said the chains lacked competitive behavior, indicated by a July 1996 memorandum by Dominick’s officials outlining an arrangement with Jewel in which Dominick’s employees would be permitted inside Jewel stores to check prices.

Can Dominick’s and Jewel now use iPhone apps to implement a collusive scheme without hiring employees to visit each other’s stores? There is a large mass of anonymous consumers. The firms offer discounts via apps. It would be in consumers’ interests to collude with each other, reject discounts and refuse to use the apps. But with a large mass of anonymous consumers, collusion is impossible to enforce. The firms can trigger a free-rider problem or prisoner’s dilemma amongst consumers so everyone uses the apps to get discounts. The market intelligence so gathered can be used by the firms to collude. As a consumer, this is the Orwellian nightmare I fear, the reverse of Richard Russo’s.

(Hat Tip: Mort Kamien told me about the milk case years ago. Perhaps he testified against the supermarket chains?)

The public interest, he said, added up to no more than the sheer number of copies the News of the World could sell. “Circulation defines the public interest” – which meant that everything was legitimate as long as the public bought the paper. “You have to appeal to what the reader wants – this is what the people of Britain wants. I was simply serving their need,” he said

Hence, if the people are willing to pay to read about Hugh Grant’s peccadilloes, then it is O.K. to hack into his phone etc. to give the people what they want. There is a flavor of a free market argument here. But we know that prices are necessary for the market to work efficiently – the market is not literally free in terms of commodities being free! There are no prices here so there is no reason why giving the public what they want leads to efficiency. Hugh Grant may value keeping the identity of the mother of his child secret at v while the public values the information at 0<v'<v . In the absence of a price, the information will get revealed even when it is inefficient (i.e it does not maximize social surplus).

Then there is the reverse scenario where details of Hugh’s shenanigans in L.A. are worth v’ to the public and secrecy is worth v to Hugh but v’>v>0. In this case the ex post efficient outcome will be implemented by the media. But there is ex ante inefficiency in gossip production. As Hugh does not capture any or the surplus he generates from cavorting with ladies of the night, he will not cavort at the socially optimal level. To fix this serious problem, Hugh and the Sun, Daily Mail etc have to begin by consulting the seminal work of Ted Groves and Myerson and Satterthwaite. A mechanism of some sort needs to be set up to maximizes second-best social welfare. I am sure someone has already worked this out in some abstract mechanism design context (Cole, Mailath and Postlewaite or Bergemann and Valimaki?). The basic idea should involve “selling the firm to the agent” or setting up transfers so each agent maximizes social surplus. This is hard to do for all agents simultaneously I would guess unless you accept some inefficiency in terms of dropping budget balance or accepting some underinvestment ex ante. But this is still better than the ad hoc mechanism we have right now where the court system makes transfers to Hugh. This wastes resources and does not result in the optimal scheme.

While we mull over what the answer might be, we can enjoy this McMullan performace:

Next Iron Chef is much better than Iron Chef. The latter almost always has Bobby Flay matching his Southwestern style cuisine against some hapless contestant who usually loses. Next Iron Chef has more uncertainty, some new faces and some better chefs. Last night’s episode had fun twists and turns coming out of the mechanism design and a tragic-comic outcome.

First, the chefs had to “bid” for ingredients in a Dutch auction with time allowed for cooking as the “currency”. There were five chefs and five ingredients. The lowest bid won for each of the first four ingredients. The chef who “won” the last ingredient was by the rules of the mechanism left with a cooking time of the lowest bid on the first four ingredients minus 5 minutes. The ingredients were revealed one by one. That was the first twist. The second was that the Chef Anne Burrell had “won” the previous episode and had an advantage coming into this one (more on this below).

Equilibrium analysis for the first twist is not available but instinct suggests very aggressive bidding towards the end since you begin bidding on the fourth ingredient knowing the maximum time you will have with the fifth. This will trigger aggressive bidding all the way through. This was true for all ingredients except sardines which Anne Burrell won for a bid of 50 minutes. Chef Alex Guarnaschelli got the last ingredient, lamb chops, with 25 minutes to cook. Since, Chef Anne had about 20 minutes more than the other chefs, she made three sardine dishes. It is always an error to make multiple dishes in this competition. The judges seem to use a lexicographic criterion. They compare your worst dish with the those of the other chefs. If your worst dish is tied with others’ dishes, then your best dish comes into play and you win. So, doing multiple dishes typically backfires because you cannot spend enough time perfecting each of your dishes so you invariably end up with the worst dish and your best dish gets ignored. The First Irony is that having more time made Chef Anne think she had to do more dishes (she did three) and one of them was Yuk.

Now the second twist: Chef Anne’s advantage was that she got to taste the other four dishes and decide which was of them was the worst. The theme of the episode was “Risk” and she decided, in my opinion voting honestly according to her preferences, that Chef Jeffrey Zakarian had the least risky dish. The two worst chefs from the first part of the competition face off in the second part. And the loser gets eliminated. Chef Anne got to chose one of the two potential losers. What if Chef Anne had voted strategically? The first instinct is to put the best chef in the knockout round but this is wrong. This chef will face one of the worst chefs in all likelihood, beat them and come back the next episode. It is is better to chose the chef you would like to face in case your dish ends up at the bottom. That chef is Chef Alex in my opinion. But Chef Anne chose Zakarian who is a star. And he defeated her in the knockout round. This is Second Irony.

Who would the judges have chosen if they had leeway? It seems Chef Alex would have been in the knockout round and probably Chef Anne would have dealt with her. This is Third Irony. This episode was Shakespearean, as Chef Alex pointed out.

Pfizer’s Lipitor, which my doctor will prescribe for me one of these days, is going off patent and facing generic competition. This leads typically to intense price competition and collapsing sales for the brand name. But Pfizer is trying to stave that off by offering deals such as a $4 co-pay rather than the $10 co-pay required with most generics. The mystery is why they are doing all this.

All the special discounts have the same impact as a price cut and the deals actually involve a price cut anyway. So, what’s in it for Pfizer?

The only rationale I can think of is that there is something weird going on at the insurance company level. That is, consumers are getting deep discounts and want to stick to their favored brand name product. So that consumers can consume what they want, the insurance companies will be forced to pay for the drug at the back end. But this does not hold water either because the insurance companies can simply stipulate that only generics be prescribed. hence, they have to be offered a deal to tick with Lipitor.

So, still the Pfizer strategy does not make sense because it replicates the Bertrand competition solution with funkier pricing schemes but no real advantage….

Q: Why did ATT attempt to merge with T-Mobile when there were huge anti-trust issues?

But the advisers that AT&T’s board were listening to most intently were the lawyers who would be on the front lines of the battle: Arnold & Porter and Crowell & Moring, which worked the antitrust strategy in Washington. (Sullivan & Cromwell worked on the deal mechanics.)

Those firms all charge by the hour, so the cynic — or skeptic — might suggest they had every incentive to push the deal ahead.

According to people involved in the decision-making process, the lawyers put the chances of success at 60 to 70 percent.

For AT&T’s board, that was a chance worth taking. The question they now must ask themselves: would they use those lawyers again?

At every OxBridge college, there is a Wine Committee. Many people want to get on it but first you have to serve on the Use of Space Committee. It might be fun if the latter plotted how the College could go to Mars. But what the committee really does is meet bi-monthly to decide where to put the photocopier. You grumble and serve as there is a chance you get on the Wine Committee.

Kellogg, as far as I am aware (!), has no Wine Committee so this cannot be used to give incentives. Monetary incentives are weak. This leaves moral suasion as the main instrument. For example, if a Dean looks miserable when he or she asks you to do something, you are likely to say yes. They look very, very sad after all, and so you would feel terrible if you refused them. To make Deans credibly miserable, they should be treated badly. QED.

This leaves open the question of why anyone would then want to become Dean. No-one has asked me (and no-one ever will!) so I have no practical experience. I guess moral suasion and guilt also operate there but am less clear as to the exact mechanism (e.g. “This institution has done so much for me, I should serve.”).

But I do have a solution that could make everyone happy – start a Wine Committee. Regular visits and tastings with wine distributors are enough to make many of us serve on the “where should the photocopiers be in the new building committee”. Then, we can treat the deans well, as they deserve, without unraveling incentives and run everything more efficiently.

A firm selling complementary products may cut the price of one to encourage sales of the other. This effect can be so strong that one of the products is sold as a loss leader:

A recent analysis from IHS iSuppli determined that Amazon’s $79 Kindle e-reader, which is the online retailer’s cheapest Kindle thus far, costs $84.25 to make…..Even if Amazon pays more to build the $79 Kindle than it sells it for, the company has several other ways to bring in money from the device. This Kindle model includes ads that show up as screensavers and at the bottom of the device’s home screen. And Amazon sees all the devices in the Kindle family — and the free Kindle apps it offers for mobile devices and computers — as a way to spur more sales of its digital e-books, music, games and apps.

In graduate school I read the masterful Introduction to Joel Mokyr’s edited volume on the British Industrial Revolution. But I did not make the Steve Jobs connection. Malcolm Gladwell did:

One of the great puzzles of the industrial revolution is why it began in England. Why not France, or Germany? Many reasons have been offered. Britain had plentiful supplies of coal, for instance. It had a good patent system in place. It had relatively high labor costs, which encouraged the search for labor-saving innovations. In an article published earlier this year, however, the economists Ralf Meisenzahl and Joel Mokyr focus on a different explanation: the role of Britain’s human-capital advantage—in particular, on a group they call “tweakers.” They believe that Britain dominated the industrial revolution because it had a far larger population of skilled engineers and artisans than its competitors: resourceful and creative men who took the signature inventions of the industrial age and tweaked them—refined and perfected them, and made them work.

In 1779, Samuel Crompton, a retiring genius from Lancashire, invented the spinning mule, which made possible the mechanization of cotton manufacture. Yet England’s real advantage was that it had….. Richard Roberts, also of Manchester, a master of precision machine tooling—and the tweaker’s tweaker. He created the “automatic” spinning mule: an exacting, high-speed, reliable rethinking of Crompton’s original creation. Such men, the economists argue, provided the “micro inventions necessary to make macro inventions highly productive and remunerative.”

Was Steve Jobs a Samuel Crompton or was he a Richard Roberts? In the eulogies that followed Jobs’s death, last month, he was repeatedly referred to as a large-scale visionary and inventor. But Isaacson’s biography suggests that he was much more of a tweaker. He borrowed the characteristic features of the Macintosh—the mouse and the icons on the screen—from the engineers at Xerox PARC, after his famous visit there, in 1979. The first portable digital music players came out in 1996. Apple introduced the iPod, in 2001, because Jobs looked at the existing music players on the market and concluded that they “truly sucked.” Smart phones started coming out in the nineteen-nineties. Jobs introduced the iPhone in 2007, more than a decade later, because, Isaacson writes, “he had noticed something odd about the cell phones on the market: They all stank, just like portable music players used to.” The idea for the iPad came from an engineer at Microsoft, who was married to a friend of the Jobs family, and who invited Jobs to his fiftieth-birthday party.

Here is the paper Gladwell mentions. Ralf Meisenzahl and Joel Mokyr conclude:

Are there any policy lessons from this for our age? The one obvious conclusion one can draw from this is that a few thousand individuals may have played a crucial role in the technological transformation of the British economy and carried the Industrial Revolution. The average level of human capital in Britain, as measured by mean literacy rates, school attendance, and even the number of people attending institutes of higher education are often regarded as surprising low for an industrial leader. But the useful knowledge that may have mattered was obviously transmitted primarily through apprentice-master relations, and among those, what counted most were the characteristics of the top few percentiles of highly skilled and dexterous mechanics and instrument-makers, mill-wrights, hardware makers, and similar artisans. This may be a more general characteristic of the impact of human capital on technological creativity: we should focus neither on the mean properties of the

population at large nor on the experiences of the “superstars” but on the group in between. Those who had the dexterity and competence to tweak, adapt, combine, improve, and debug existing ideas, build them according to specifications, but with the knowledge to add in what the blueprints left out were critical to the story. The policy implications of this insight are far from obvious, but clearly if the source of technological success was a small percentage of the labor force, this is something that an educational policy would have to take into account.

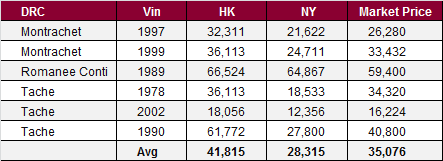

Prices are in british pounds/case of high end Burgundy. Why aren’t the producers shifting stock to Hong Kong? Also, it costs about $40 to ship a case from New York City to Hong Kong so buyers can easily resell or transport their purchase abroad. There must be some tax implication but surely it can’t justify this spread.

Prices are in british pounds/case of high end Burgundy. Why aren’t the producers shifting stock to Hong Kong? Also, it costs about $40 to ship a case from New York City to Hong Kong so buyers can easily resell or transport their purchase abroad. There must be some tax implication but surely it can’t justify this spread.

I leave it to Paul Krugman to advice Greece. I’ll stick to Greeks. In a couple of weeks from now, while everyone is at the rally complaining about the austerity plan, the government will shut down all banks. They will get out of the euro. On Monday, Greek ATMs will issue euronotes with a picture of Plato photoshopped onto them. They will be called drachmas. Plato’s picture will cause the value of the note to fall to a fraction of the value of the euro. So, in the next couple of weeks, following the simplest prescription of Hirschman’s Exit, Voice and Loyalty, Greeks should move all their bank accounts abroad. Of course, the country that gave us Plato, Aristotle, Pythagoras and, my personal favorite, Thucydides, does not need my shallow advice. Via the Daily Mail:

Fat-cat Greeks have secretly shifted more than €228billion euros out of their country’s crisis-hit banks and into accounts in Switzerland, according to a report.

The big money is fleeing the country as rich Greeks fear the possible re-introduction of their old currency, the drachma, would instantly halve the value of their euros if they are left in Greek banks.

Netflix has increases prices. What should Redbox, the kiosk DVD rental firm do? Thye could cut or maintain prices and gain share. Or they could raise prices, lose some sales and gain margin. Redbox has decided to raise prices:

The new rental rate will be $1.20 per day, instead of the current $1 daily rate. Redbox prices will remained unchanged for Blu-ray discs at $1.50 per day and video games at $2 per day.

Why don’t companies do this more often? One explanation:

[I]t spooked investors, especially because Redbox appears to be picking up customers still stewing over the higher prices at Netflix. Coinstar’s shares plunged 10 percent in Thursday’s extended trading.

To outsiders, sales are more observable than profits/unit, because variable costs are kept private by firms but sales figures are publicized. The market can see lower sales but has a harder time calculating the profit implications – lower sales could mean higher profits. Or stock market analysts are crazy short termists.

All Cambridge (U.K.) undergrads have (had?) to struggle through a chapter by chapter reading of Keynes’ General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Some come out of this confirmed Keynesians and even Marxists and then go on to work in the City of London. This rich irony comes at the cost of some confusion for hordes of the intellectual elite as the book is extremely hard to read. It turns out that Keynes offered a lucid synopsis of his theory in the QJE in a reply to his critics. My only quibble is that I wish he had used the odd equation here or there – he speaks in equations but does not dare spell them out presumably for fear of losing his reader. But here is a spectacular passage on uncertainty vs risk:

Why does it matter? Because it affects demand for money and hence the interest rate:

The whole article is full of amazing insights. i’s are not dotted or t’s crossed. Many papers remain to be written.

(Hat Tip: Nabil Al-Najjar)

Social Choice Theorists are going to see an experiment in action as San Francisco votes for a new mayor using rank-order voting. Here is how it works:

Each voter lists up to three candidates in ranked order: First, second and third choice.

If one candidate gets more than 50 percent of the first-place votes in the first round of counting, he’s the winner and there’s no need to look at the second and third choices.

But if no one has a majority, the candidate with the fewest number of votes is eliminated from the future count and his second-choice votes are distributed to the remaining candidates.

If still no one cracks the 50 percent mark, then the candidate with the second-lowest vote total is eliminated and his second-place votes are distributed. If the voters’ second choice already was eliminated, it’s the third-choice vote that goes back into the pool.

This continues until one candidate has a majority of the remaining votes. Last November, it took 20 rounds before Malia Cohen finally was elected as supervisor from San Francisco’s District 10.

There are two strategic issues. First, there must be an incentive for strategic voting via Gibbard-Satterthwaite/Arrow. Hence, sincere voting and strategic voting will differ. Second, the candidate positions and in fact the issue of who enters as a candidate is a key factor in the rationale for switching to rank order voting in the first place. Some voters must hope that third party candidates can now enter and have a chance of winning. Others must hope that more centrist policies are adopted by the candidates in the hope of being voters’ second or third choice.

I assume there are many formal theory papers in political science on this but am not familiar with them…anyone have any ideas?

Bruce Riedel who ran President Obama’s AfPak review now favors containment over engagement:

It is time to move to a policy of containment, which would mean a more hostile relationship. But it should be a focused hostility, aimed not at hurting Pakistan’s people but at holding its army and intelligence branches accountable. When we learn that an officer from Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence, or ISI, is aiding terrorism, whether in Afghanistan or India, we should put him on wanted lists, sanction him at the United Nations and, if he is dangerous enough, track him down. Putting sanctions on organizations in Pakistan has not worked in the past, but sanctioning individuals has — as the nuclear proliferator Abdul Qadeer Khan could attest.

It is useful to think of the US-Pakistan game as a principal-agent relationship. The US (principal) would like to “pay for performance” and make a transfer if and only if the Pakistani army (agent) capture terrorists and quash the Taliban. Performing this task is costly for Pakistan for many reasons. For one, they use the terrorists as proxies in their fight against India. But if the US values elimination of terrorists enough, there is a transfer or sequence of transfers that are large enough to persuade Pakistan to work hard on America’s behalf. For the transfer scheme to work, the US has to be able to commit to pay. If Pakistan is too successful, then the US has no incentive continue paying them. Knowing this, Pakistan does not want to work too hard on America’s behalf. Do enough work to keep the money rolling in but not enough to kill off the goose laying golden eggs.

This delicate balancing act can tip one way or another with random events. After one huge such event, the capture of Osama Bin Laden, the relationship has gone sour. Perhaps, we are in a new phase, that is the gist of Riedel’s column. But how should this be managed? I need to think about part 2….

Kevin Murphy is a John Bates Clark Medal winner, he has a MacArthur “Genius” Award and is a superstar in the economics profession. But the green-eyed monster has finally stirred because I found out he is consulting for the basketball players in the current labor negotiations.

Teams pay a luxury tax if they go over a salary cap specified by the league. The revenue generated by the tax is transferred to the other teams. If the luxury tax is too high, teams will not go over the salary cap and the labor market for payers will be moribund. But if it is low, the rich teams will go over the salary cap and the poorer teams will get the revenue this generates and will themselves compete to hire players. The labor market for players will be active. There is some threshold luxury tax below which the market is active and above which it is inactive. The players want a tax that is below the threshold. Who might be able to work out this threshold? Kevin Murphy:

[An ESPN reporter] asked a union official how they know where that player-friendly effect stops, and where the de facto hard cap kicks in.

His answer was that their economist Kevin Murphy had the task of predicting how owners would spend under the last CBA, back when it was new. Looking back, they realize his work was, the official says, “pretty much perfect.”

Who is the consultant to the teams I wonder?

(HT: MR)

Tom Sargent on why he joined NYU:

”I need other people to do my best work. Economics is like sports — the real stuff is being done by young guys, and you have to work hard to keep up with them. Old guys like me are like boxers — we’ve seen a lot of moves, but our reflexes are slower. There are a lot of young guys here to keep me sharp.”

To add to this: when someone comes up with some supposedly “new” moves, old guys can tell whether they are reinventing the wheel or whether it is a really new move. Zvi Griliches used to play this role at Harvard. Does this knowledge help you to come up with some really new moves yourself? I’m not sure.

Why would a narrow elite ever extend the vote to the masses? Perhaps the hand of the elite is forced by the threat of revolution. To convince the masses that the elite is committed to giving them surplus, the elite extend the franchise. This is argument of Acemoglu and Robinson.

Lizzeri and Persico have a quite different argument which has particular resonance for Britain’s Age of Reform in the nineteenth century. Suppose only a fraction of the population can vote. Two parties, the Whigs and the Tories compete for their vote. The parties can either offer a public good or a transfer with revenue generated via taxation. When the enfranchised group is a small elite, there is an incentive to tax the entire population and then target transfers to swing voters in the elite. That way a party can give them as much as they would get with pubic good provision and get into power. The mass of the elite that is not targeted gets no transfer.

When the franchise is extended pork barrel politics is not as powerful as the taxable endowment is not large enough to offer the now larger majority enough to compensate them for zero pubic good production. Each political party can at least get a 50% chance of getting elected by offering public goods. Hence, an extension of the franchise leads to less pork barrel politics and more public good production. Some members of the elite are indifferent to this change and others – those who were not receiving transfers when the franchise was small – strictly prefer it. Hence, extension of the franchise Pareto-dominates a small franchise. The franchise can be extended even when there is no threat of revolution by the disenfranchised masses.

The Pareto-domination property does not obtain in general (when voters are ideological and pubic good production is not zero-one) but the majority of the elite prefers extension of the franchise. In nineteenth century Britain, members of the elite clamoured for the extension of the franchise. There was less pork barrel transfer and more public good production after the franchise was extended.

Students anywhere can watch my old friend Ben Polak teach his famous Yale class. They can’t get a Yale grade for the class but that possibility is coming ever closer: A professor at Stanford is teaching a robotics class and everyone can sign up, do the assignments, take the exams and get a certificate of “accomplishment. Prospective employers do not know whether your friend took the exam for you. This means the certificate has little value. But surely it is only a matter of time before some verification mechanism is set up and this problem is dealt with.

The implications of this change are multifold but I just want to focus on one: the impact on the research university. Universities produce research as well as teaching and this other dimension is often forgotten in all the discussion of virtual teaching. Here is one possible sequence of events:

1. Virtual teaching cannibalizes face-to-face teaching. Tuition goes down and courses become quite cheap.

2. This destroys tuition-based universities which turn into vast teaching factories. A few universities try an “elite” approach with tiny classes taught by excellent teachers.

3. Endowment based universities continue to survive. Researchers become concentrated in these universities. They compete for government funding and do mainly PhD teaching.

4. A “top heavy” university structure emerges with a handful of research universities and a number of vast teaching universities.

This analysis assumes there is weak complementarity between research and teaching. If there is strong complementarity, the teachers have to be researchers to keep courses up to date, exciting etc. This will make step 2 above more difficult and leave a structure like today’s but with universities having virtual counterparts and huge scale.

Dodd-Frank contained the so-called Durbin amendment which capped debit card fees that could be charged to merchants. And now banks are charging $5/month to card holders because

[A]s Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, put it after passage last year of the Dodd-Frank Act, “If you’re a restaurant and you can’t charge for the soda, you’re going to charge more for the burger.”

But if you can charge for the burger, why weren’t you charging for it in the first place? There is a good reason why a bank could charge for the debit card: It is tied to a checking account and the cost of switching to a new bank will mean that the bank can get away with a small fee without much drop off in demand deposits. So to paraphrase Dimon:

“If you’re a restaurant and you can charge for a burger, you’re going to charge for it, whether the soda is free or not.”

Suppose you are going to fly Delta from O’Hare to Atlanta. You could buy a ticket now for price p or try to get a ticket later at the last minute. After all, later on you will have a more accurate picture of your willingness to pay for the flight. Luckily for you, Delta has adopted a bidding system where you can compensate another passenger who gets bumped to seat you. How does the bidding procedure affect Delta’s incentives to overbook or underbook the flight? How does it affect the initial price p?

First, there is some “marginal consumer” who is indifferent between paying p for the flight now or waiting and taking their chances in the bidding system. Consumers with “higher” signals than the marginal consumer strictly prefer to buy at price p and are left with surplus. Consumers with “lower” signals strictly prefer to wait and take their chances. Opening up the bidding system increases the value of the ticket to the marginal buyer: now he has the option of reselling it and capturing some of the rents from people who find they desperately need to go to Atlanta after all. This extra rent is simply recaptured by the seller by raising the price p. This has the additional benefit that more rent is extracted from consumers with higher signals. Finally, to make the resale market active, Delta had better overbook the flight.

I am attending an antitrust conference hosted by the Searle Center at Northwestern University. In my attempt to Americanize, I am drawn to any paper involving sport. And if British sport is thrown in for comparison, resistance is impossible.

Haddock, Jacobi and Sag offer an analysis of American NFL football stadiums versus English soccer stadiums. Their thesis is simple: the NFL controls entry of new teams in the league and teams can move from one city to another. So, if the New Jersey government does not cough up $1 billion for the New Meadowlands, teams can threaten to move and the NFL can refuse to allocate another team to the state. For example:

When the Houston Oilers threatened to move to Jacksonville, Florida in 1987 Harris County, Texas, responded with $67 million in improvements to the funded by property tax increases, doubling the county’s hotel tax, and underwriting bonds to be paid over the next 30 years. Within six years the Oilers began lobbying for a new stadium with club seating. Rather than opposing the Oilers rent seeking, NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue warned Houston that “If the Oilers’ situation doesn’t work down there, I don’t see any circumstances in which we’re going to guarantee a team, especially when one team’s already found it unsatisfactory.” The message was clear, if Houston lost the Oilers because it refused to accede to the team’s demands, it was unlikely to receive a prompt replacement. At the end of the 1996 season the Oilers left Houston for Nashville where city officials had promised to contribute $144 million toward a new stadium.

In England, entry is easy. If a team attempts to hold up a city, it can create its own new team. This reduces the bargaining power of the team.

Jerry Hausman, the discussant, found much to disagree with. Hausman claimed many British teams were simply no-hopers. Very few teams are actually competitive. Arsenal is not one of them and hence no-one would fund a stadium for them. In the NFL, many teams are competitive. Hence, they can extract rents from the local community. He thought politics was an the center of problem: Why did Massachusetts fund a new high school in Newton rather than soend money in poorer areas? He displayed a surprising amount of knowledge about English soccer and claimed to have worked for the Chicago Bulls (I didn’t catch what he did for them). He speaks fast so I may have missed some details.

David Pogue has also been thinking/fuming about the Netflix price change which effectively increases prices from $10 to $16 for streaming plus one-DVD-at-a-time. He ends with:

[W]hat makes me unhappiest is how calculated all of this feels. In July, a spokesman told me that Netflix had already taken the subscriber defection into account in its financial forecasts.

And sure enough. When I tweeted that Netflix had lost one million of its 25 million customers, @npe9 nailed it when he wrote:“It damages their brand and images, but 24 million customers paying $16 is still better than 25 million @ $10. Increases revenue by >50%.”