You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘sport’ tag.

Tennis scoring differs from basketball scoring in two important ways. First, in tennis, points are grouped into games (and games into sets) and the object is to win games, not points. If this were the only difference, then it would be analogous to the difference between a popular vote and the electoral college in US Presidential elections.

The other difference is that in basketball the team with the highest score at the (pre-determined) end of the game wins, whereas in tennis winning a game requires a pre-specified number of points and you must win by two. The important difference here is that in tennis you know which are the decisive points whereas in basketball all points are perfect substitutes.

Then to assess statistically whether tennis’ unique scoring system favors the stronger or weaker player (relative to a cumulative system like basketball) we could do the following. Count the total number of points won by each player in decisive and non-decisive points separately (perhaps dividing the sample first according to who is serving.) First ask whether the score differential is different for these two scenarios. One would guess that it is and that the stronger player has a larger advantage in the decisive points. (According to my theory, the reason is that the stronger player can spend less effort on the non-decisive points and still be competitive, thus reserving more effort for the decisive points.) Call this difference-in-differential the decisiveness effect.

Then compare matches pitting two equal-strength players with matches pitting a stronger player against a weaker player. Ask whether the decisiveness effect is larger when the players are unequally matched. If so, then that would suggest that grouped scoring accentuates the advantage of the stronger player.

The US Open is here. From the Straight Sets blog, food for thought about the design of a scoring system:

A tennis match is a war of attrition that is won after hundreds of points have been played and perhaps a couple of thousand shots have been struck.On top of that, the scoring system also very much favors even the slightly better player.

“It’s very forgiving,” Richards said. “You can make mistakes and win a game. Lose a set and still win a match.”

Fox said tennis’s scoring system is different because points do not all count the same.

“Let’s say you’re in a very close match and you get extended to set point at 5-4,” Fox said, referring to a best-of-three format. “There may be only four or five points separating you from you opponent in the entire match. And yet, if you win that first set point, you’ve essentially already won half the match. Half the match! And not only that — your opponent goes back to zero. They have to start completely over again. And the same thing happens in every game, not just each set. The loser’s points are completely wiped out. So there are these constant pressure points you’re facing throughout the match.”

There are two levels at which to assess this claim, the statistical effect and the incentive effect. Statistically, it seems wrong to me. Compare tennis scoring to basketball scoring, i.e. cumulative scoring. Suppose the underdog gets lucky early and takes an early lead. With tennis scoring, there is a chance to consolidate this early advantage by clinching a game or set. With cumulative scoring, the lucky streak is short-lived because the law of large numbers will most likely eradicate it.

The incentive effect is less clear to me, although my instinct suggests it goes the other way. Being a better player might mean that you are able to raise your level of play in the crucial points. We could think of this as having a larger budget of effort to allocate across points. Then grouped scoring enables the better player to know which points to spend the extra effort on. This may be what the latter part of the quote is getting at.

Paul Kedrosky is intrigued by a claim about golf strategy

While eating lunch and idly scanning subtitles of today’s broadcast of golf’s PGA Championship, I saw an analyst make an interesting claim. He said that the best putters in professional golf make more three putts (taking three putts to get the ball in the cup) than does the average professional golfer. Why? Because, he argued, the best putters hit the ball more firmly and confidently, with the result that if they miss their ball often ends up further past the hole. That causes them to 3-putt more often than do “lag” putters who are just trying to get the ball into the hole with no nastiness.

The hypothesis is that the better putters take more risks. That is, there is a trade-off between average return (few putts on average) and risk (chance of a big loss: three putts.)

His is a data-driven blog and he confronts the claim with a plot suggesting the opposite: better putters have fewer three-puts. However, there are reasons to quibble with the data (starting a long distance from the green, it would be nearly impossible to hole out with a single putt. In these cases good putters will two-putt, average putters will three-putt. The hypothesis is really about putting from around 10 feet and so the data needs to control for distance, as suggested to me by Mallesh Pai. Alternatively, instead of looking at cross-sectional data we could get data on a single player and compare his risk-taking behavior on easier greens, where he is effectively a better putter, versus more difficult greens.)

And anyway, who needs data when the theory is relatively straightforward. Any individual golfer has a risk-return tradeoff. He can putt firmly and try to increase the chance of holing out in one, at the cost of an increase in the chance of a three-putt if he misses and goes far past the hole. The golfer chooses the riskiness of his putts to optimize that tradeoff. Now, we can formalize what it means to be a better putter: for an equal increase in risk of a three-putt he gets a larger increase in the probability of a one-putt. Then we can analyze how this shift in the PPF (putt-possibility-frontier) affects his risk-taking.

Textbook Econ-1 micro tells us that there are two effects that go in opposite directions. First, the substitution effect tells us that because a better putter faces a lower relative price (in terms of increased risk) from going for a lower score, he will take advantage of this by taking more risk and consequently succumbing to more three-putts. (This assumes diminishing Marginal Rate of Substitution, a natural assumption here.) But, there is an income effect as well. His better putting skills enable him to both lower his risk and lower his average number of putts, and he will take advantage of this as well. (We are assuming here that lower risk and lower score are both normal goods.) The income effect points in the direction of fewer three-putts.

So the theoretical conclusions are ambiguous in general, but there is one case in which the original claim is clearly borne out. Consider putts from about 8 feet out. Competent golfers can, if they choose, play safely and virtually ensure they will hole out with two putts. Competent, but not excellent golfers, have a PPF whose slope is greater than 1: to increase the probability of a 1-putt, they must increase by even more the probability of a three-putt. Any movement along such a PPF away from the sure-thing two-putt not only increases risk, but also increases the expected number of putts. Its unambiguosly a bad move. So competent, but not excellent golfers will be at a corner solution on 8 foot putts, always two-putting.

On the other hand, better golfers have a flatter PPF and can, at least marginally, reduce their average number of putts by taking on risk. Some of these better golfers, in some situations, will choose to do this, and run the risk of three-putting.

Thanks to Mallesh Pai for the pointer.

Via kottke.org, an article in New Scientist on the mathematics of gambling. One bit concerns arbitrage in online sports wagering.

Let’s say, for example, you want to bet on one of the highlights of the British sporting calendar, the annual university boat race between old rivals Oxford and Cambridge. One bookie is offering 3 to 1 on Cambridge to win and 1 to 4 on Oxford. But a second bookie disagrees and has Cambridge evens (1 to 1) and Oxford at 1 to 2.

Each bookie has looked after his own back, ensuring that it is impossible for you to bet on both Oxford and Cambridge with him and make a profit regardless of the result. However, if you spread your bets between the two bookies, it is possible to guarantee success (see diagram, for details). Having done the calculations, you place £37.50 on Cambridge with bookie 1 and £100 on Oxford with bookie 2. Whatever the result you make a profit of £12.50.

I can verify that arbitrage opportunites abound. In my research with Toomas Hinnosaar on sorophilia, we investigated an explanation involving betting. In the process we discovered that the many online bookmakers often quote very different betting lines for basketball games.

How could bookmakers open themselves up to arbitrage and still stay in business? Here is one possible story. First note that, as mentioned in the quote above, no one bookmaker is subject to a sure losing bet. The arbitrage involves placing bets at two different bookies.

Now imagine you are one of two bookmakers setting the point spread on a Clippers-Lakers game and your rival bookie has just set a spread of Lakers by 5 points. Suppose you think that is too low and that a better guess at the spread is Lakers by 8 points. What spread do you set?

Lakers by 6. You create an arbitrage opportunity. Gamblers can place two bets and create a sure thing: with you they take the Clippers and the points. With your rival they bet on the Lakers to cover. You will win as long as the Lakers win by at least 7 points, which is favorable odds for you (remember you think that Lakers by 8 is the right line.) Your rival loses as long as the the Lakers win by at least 6 points, which is unfavorable odds for your rival. You come away with (what you believe to be) a winning bet and you stick your rival with a losing bet.

Now this begs the question of why your rival stuck his neck out and posted his line early. The reason is that he gets something in return: he gets all the business from gamblers wishing to place bets early. Put differently, when you decided to wait you were trading off the loss of some business during the time his line is active and yours is not versus the gain from exploiting him if he sets (what appears to you to be) a bad line.

Since both of you have the option of playing either the “post early” or “wait and see” strategy, in equilibrium you must both be indifferent so the costs and benefits exactly offset.

Of course, with online bookmaking the time intervals we are talking about (the time only one line is active before you respond, and the time it takes him to adjust to your response, closing the gap) will be small, so the arbitrage opportunities will be fleeting. (As acknowledged in the New Scientist article.)

The governing body of international swimming competition FINA is instituting a ban on the high-tech swimsuits that have been used to set a flurry of new world records.

In the 17 months since the LZR Racer hit the market and spawned a host of imitators, more than 130 world records have fallen, including seven (in eight events) by Michael Phelps during the Beijing Olympics.

Phelps, a 14-time Olympic gold medalist, applauded FINA’s proposal that racing suits be made of permeable materials and that there be limits to how much of a swimmer’s body could be covered. The motion must be approved by the FINA Bureau when it convenes Tuesday.

I see two considerations at play here. First, they may intend to put asterisks on all of the recent records in order to effectively reinstate older records by swimmers who never had the advantage of the new suits. For example,

Ian Thorpe’s 2002 world best in the men’s 400 meters freestyle final was thought to be as good as sacred but Germany’s Paul Biedermann swam 3 minutes 40.07 to beat the mark by one hundredth of a second and take gold.

Its hard to argue with this motivation, but it necessitates a quick return to the old suits in order to give current swimmers a chance to set un-asterisked records while still at their peak. However the ban does not go into effect until 2010.

Don’t confuse this with the second likely motivation which is to put a halt to a technological arms race. That is also the motivation behind banning performance-enhancing drugs. The problem with an arms race is that every competitor will be required to arm in order to be competitive and then the ultimate result is the same level playing field but with the extra cost of the arms race.

On the other hand, allowing the arms race avoids having to legislate and litigate detailed regulations. If we just gave in and allowed performance-enhancers then we would have no drug tests, no doping boards, no scandals. If we ban the new swimsuits we still have to decide exactly which swimsuits are legal. And we go back to chest- and leg-hair shaving. Plastic surgery to streamline the skin?

Swimsuits don’t cause harm like drugs do. Since the costs are relatively low, there is a legitimate argument for allowing this arms race and avoiding having to navigate a new thicket of rules.

Here is an excellent example of social choice paradoxes in practice: the voting system for the Olympic Venue. The article illustrates cycles, failure of unanimity and violations of independence of irrelevant alternatives. A great teaching aid, I will certainly be using it next time I teach my intermediate micro course. I thank Taresh Batra for the pointer.

By the way, there is another perfect social choice example from the olympics. In the 2002 women’s figure skating competition, Michelle Kwan was leading Sarah Hughes when the final skater, Irina Slutskaya took the ice. Slutskaya put in a sub-par performance which was nevertheless good enough to surpass Kwan. But the real suprise was that this performance by Slutskaya reversed the ranking of Kwan and Hughes so that Hughes leaped ahead of both Kwan and Slutskaya and won the gold. In the end, Hughes took the gold, Slutskaya took silver, and Kwan went home with the bronze medal. Here is a an old story.

Jonah Lehrer illustrates a common misunderstanding of (im)probability. He writes:

It’s been a hotly debated scientific question for decades: was Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak a genuine statistical outlier, or is it an expected statistical aberration, given the long history of major league baseball?

He is referring to the observation that 56-game hitting streaks while intuitively improbable will nevertheless happen when the game has been around for long enough. Does this make it less of a feat?

- Say I have a monkey banging on a keyboard. Take any seqeunce of letters. The chance that the monkey will bang out that particular sequence is impossibly small. But one sequence will be produced. When we see that sequence produced do we change our minds and say that’t not so surprising after all because there was certain to be one unlikely sequence produced? No. Similarly, the chance that somebody will hit safely in 56 straight games could be high, but the chance that it will be player X is small. Indeed, that probability is equal to the probability that player X is the greatest streak hitter ever to play the game. So if X turns out to be Joe DiMaggio then we conclude that Joe DiMaggio indeed accomoplished quite a feat.

- We might be asking a different question. We grant that DiMaggio achieved the highly improbable and hit for the longest streak of any player in history, but we ask whether 56 is really all that long? After all, he didn’t hit for 57, which is even less likely. To address this question we might ask, on average, how many players “should” hit safely in 56 straight games in the time that the game has been around? But this question is very easy to answer. Our best estimate of the expected number of players to hit 56-game streaks is 1, the actual number. (Because the number is close to zero, this estimate is noisy, but this is still the best estimate without making any assumptions about the underlying distribution.)

Top chess players, until recently, held their own against even the most powerful chess playing computers. These machines could calculate far deeper than their human opponents and yet the humans claimed an advantage: intuition. A computer searches a huge number of positions and then finds the best. For an experienced human chess player, the good moves “suggest themselves.” How that is possible is presumably a very important mystery, but I wonder how one could demonstrate that qualitatively the thought process is different.

Having been somewhat obsessed recently with Scrabble, I thought of the following experiment. Suppose we write a computer program that tries to create words from scrabble tiles using a simple brute-force method. The computer has a database of words. It randomly combines letters and checks whether the result is in its database and outputs the most valuable word it can identify in a fixed length of time. Now consider a contest between to computers programmed in the same way which differ only in the size of their database, the first knowing a subset of the words known by the second. The task is to come up with the best word from a fixed number of tiles. Clearly the second would do better, but I am interested in how the advantage varies with the number of tiles. Presumably, the more tiles the greater the advantage.

I want to compare this with an analogous contest between a human and a computer to measure how much faster a superior human’s advantage increases in the number of tiles. Take a human scrabble player with a large vocabulary and have him play the same game against a fast computer with a small vocuabulary. My guess is that the human’s advantage (which could be negative for a small number of tiles) will increase in the number of tiles, and faster than the stronger computer’s advantage increased in the computer-vs-computer scenario.

Now there may be many reasons for this, but what I am trying to get at is this. With many tiles, brute-force search quickly plateaus in terms of effectiveness because the additional tiles act as noise making it harder for the computer to find a word in its database. But when humans construct words, the words “suggest themselves” and increasing the number of tiles facilitates this (or at least hinders it more slowly than it hinders brute-force.)

Wimbledon, which has just gotten underway today, is a seeded tournament, like all major tennis events and other elimination tournaments. Competitors are ranked according to strength and placed into the elimination bracket in a way that matches the strongest against the weakest. For example, seeding is designed so that when the quarter-finals are reached, the top seed (the strongest player) will face the 8th seed, the 2nd seed will face the 7th seed, etc. From the blog Straight Sets:

When Rafael Nadal withdrew from Wimbledon on Friday, there was a reshuffling of the seeds that may have raised a few eyebrows. Here is how it was explained on Wimbledon.org:

The hole at the top of the men’s draw left by Nadal will be filled by the fifth seed, Juan Martin del Potro. Del Potro’s place will be taken by the 17th seed James Blake of the USA. The next to be seeded, Nicolas Kiefer moves to line 56 to take Blake’s position as the 33rd seed. Thiago Alves takes Kiefer’s position on line 61 and is a lucky loser.

Was this simply Wimbledon tweaking the draw at their whim or was there some method to the madness?

Presumably tournaments are seeded in order to make them as exciting as possible for the spectators. One plausible goal is to maximize the chances that the top two players meet in the final, since viewership peaks considerably for the final. But the standard seeding is not obviously the optimal one for this objective: it makes it easy for the top seed to make the final but hard for the second seed. Switching the positions of the top ranked and second ranked players might increase the chances of having a 1-2 final.

You would also expect that early round matches would be more competitive. Competitiveness in contests, like tennis matches, is determined by the relative strength of the opponents. Switching the position of 1 and 2 would even out the matches played by the top player at the expense of unbalancing the matches played by the second player, the average balance across matches would be unchanged. If effort is concave in the relative strength of the opponents then the total effect would be to increase competitiveness.

When you start thinking about the game theory of tournaments, your first thought is what has Benny Moldovanu said on the subject. And sure enough, google turns up this paper by Groh, Moldovanu, Sela, and Sunde which seems to have all the answers. Incidentally, Benny will be visiting Northwestern next fall and I expect that he will be bringing his tennis racket…

Behavioral economists Devin Pope and Maurice Schweitzer have a new paper showing that professional golfers perform differently on putts that are identical in all respects except that one is for par and one is for birdie. What does “identical in all respects mean?” From a summary in the New York Times:

The professors, Devin Pope and Maurice Schweitzer, seemingly anticipated every “But what about?” reflex from golf experts. The tendency to miss birdie putts more often existed regardless of the player’s general putting or overall skill; round or hole number; putt length; position with respect to the lead or cut; and more.

They find that par putts are made more often than birdie putts. One natural response might be the following. If the putt is for par, then the golfer is, on average, farther behind than if the putt is for birdie. And when you are farther behind you have an incentive to take greater risk. In putting, you can increase the chance of making a putt at the expense of a more difficult next putt if you miss (by say using a firmer stroke.) You would have more incentive to do this when you are farther behind. (Then you care less about the consequences in the event of missing since in that event you are even further behind.)

But they apparently control for this by matching par putts with birdie putts that are identical in terms of the total score that would result from sinking them. They find the bias is still there. (See Column 8 of Table 3 in their paper.)

However, you might say that this means that the bias is not due to loss aversion. Because in these two matched settings the golfer is at the same point relative to any reference point. And if you appeal to “narrow framing” by saying that the players are using a hole-by-hole reference point of par, then the same narrow framing makes it rational to take risks when the putt is for par and play it safe when the putt is for birdie.

A real smoking gun would be the following. Take the birdie and par putts matched in terms of score conditional on sinking the putt. Now ask what is the expected final score, or tournament rank, or prize money, or other measure of success, conditional on whether the putt was for birdie or bogey. The null hypothesis is that these would be the same. Loss aversion would imply that they are not the same, although it is not obvious which direction it would go. (The authors do a back of the envelope calculation to address a related question in their concluding section. They find that the apparent loss aversion matters for final scores but they don’t seem to include any of the controls from the earlier parts of the paper in this calculation.)

(Gatsby greeting: kottke.org)

Thursday night we had another overtime game in the NBA finals. For the sake of context, here is a plot of the time series of point differential. Orlando minus LA.

A few of the commenters on the previous post nailed the late-game strategy behind the eye-popping animation. First, at the end of the game, the team that is currently behind will intentionally foul in order to prevent the opponent running out the clock. The effect of this in terms of the histogram is that it throws mass out away from zero. But the ensuing free-throws might be missed and this gives the trailing team a chance to close the gap. So the total effect of this strategy is to throw mass in both directions.

If the trailing team is really lucky both free throws will be missed and they will score on the subsequent possession and take the lead. Now the other team is trailing and they will do the same. So we see that at the end of the game, no matter where we are on that histogram, mass will be thrown in both directions, until either the lead is insurmountable, or we land right at zero, a tie game.

Once the game is tied there is no more incentive to foul. But there is also no incentive to shoot (assuming less than 24 seconds to go.) The leading team will run the clock as far as possible before taking one last shot.

So there are two reasons for the spike: risk-taking strategy by the trailing team increases the chance of landing at a tie game, and then conservative strategy keeps us there. The following graphic (again due to the excellent Toomas Hinnosaar) illustrates this pretty clearly.

In blue you have the distribution of point differences that we would get if we pretented that the teams’ scoring was uncorrelated. This is what I referred to as the crude hypothesis in the previous post. In red you see the extra mass from the actual distribution and in white you see the smaller mass from the actual distribution. We see that the actual distribution is more concentrated in the tails (because there is less incentive to keep scoring when you are already very far ahead), less concentrated around zero (because of risk-taking by the trailing team) and much more concentrated at the point zero (because of conservative play when the game is tied.)

In blue you have the distribution of point differences that we would get if we pretented that the teams’ scoring was uncorrelated. This is what I referred to as the crude hypothesis in the previous post. In red you see the extra mass from the actual distribution and in white you see the smaller mass from the actual distribution. We see that the actual distribution is more concentrated in the tails (because there is less incentive to keep scoring when you are already very far ahead), less concentrated around zero (because of risk-taking by the trailing team) and much more concentrated at the point zero (because of conservative play when the game is tied.)

Now, this is all qualitatively consistent with the end-of-regulation histogram and with the animation. The big question is whether it can explain the size of that spike quantitatively. Obviously, not all games that go into overtime follow this pattern. For example, Thursday’s game did not feature intentional fouling at the end. How can we assess whether sound strategy alone is enough to explain the frequency of overtime?

There have been quite a few overtime games in the NBA playoffs this year. We have had one in the finals already and in an earlier series between the Bulls and Celtics, 4 out of 7 games went into overtime, with one game in double overtime and one game in triple overtime!

How often should we expect a basketball game to end tied after 48 minutes of play? At first glance it would seem pretty rare. If you look at the distribution of points scored by the home teams and by the visiting teams separately, they look pretty close to a normal distribution with a large variance. If we made the crude hypothesis that the two distributions were statistically independent, then ties would indeed be very rare: 2.29% of all games would reach overtime.

But the scoring is not independent of course. Similar to a marathon, the amount of effort expended is different for the team currently in front versus the team trailing and this amount of effort also depends on the current point differential. But such strategy should have only a small effect on the probability of ties. The team ahead optimally slows down to conserve effort, balancing this against the increased chance that the score will tighten. Also, conservation of effort by itself should generally compress point differentials, raising not just the frequency of ties, but also the frequency of games decided by one or two points.

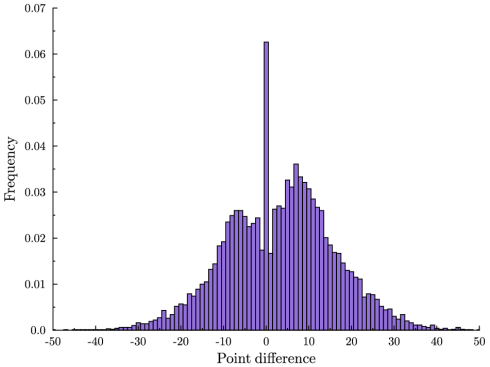

But overtime is almost 3 times more frequent than this: 6.26% of all NBA games are tied at the end of regulation play. And games decided by just a few points are surprisingly rare: It is more likely to have a tie than for the game to be decided by two points, and a tie is more than twice as likely as a one-point difference. These statistics are quite dramatic when you see them visually.

Here is a frequency histogram of the difference in points between the home team and visiting team at the end of regulation play. These are data from all NBA games 1997-2009. A positive number means that the home team won, a zero means that the game was tied and therefore went into overtime. Notice the massive spike at zero.

(There is also more mass on the positive end. This is the well-known home team bias.)

What explains this? A star PhD student at Northwestern, Toomas Hinnosaar, and I have been thinking about this. Our focus in on the dynamics and strategy at the end of the game. To give you some ideas, Toomas created the following striking video. It shows the evolution of the point differential in the last 40 seconds of the fourth quarter. At the beginning, the distribution looks close to normal. This is what the crude hypothesis above would predict. Watch how the spike emerges in such a short period of time.

By contrast, here is the same animation at the end of halftime. Nothing unusual.

Storn White, lifestyle artist.

Here is an interesting article about the history of the Ivy league and the member Universities’ attitudes toward sport.

The Ivy is never going to be the Southeastern Conference—and nobody is suggesting it should be. The schools don’t need the exposure of sports to attract students and alumni donations. But some of the league’s alumni complain that the schools offer their students the best of everything, except in this one area. “Why not give them the same opportunities and the same platform in athletics that you do in academics?” says Marcellus Wiley, a former NFL defensive end who played at Columbia in the 1990s. “I think they should revisit everything.”

If we take the objective to be maintaining reputation and attracting donations then there is a broader question. Why is the concentration among schools which compete on academic excellence so much higher than among those that compete on athletics? Competition for dominance in sport appears to be more costly and occurs at a higher frequency that the competition for academic excellence. Some possible reasons:

- There is more variance in academic talent than in talent in sports. Thus the top end is thinner and the market is smaller.

- There is more continuity in academic strength purely because of numbers. A bad recruiting class for the basketball team a few years in a row and you are back to square one. A freshman class at Harvard is large enough that variations wash out.

- It is easier to throw money at sport. One coach makes the whole program. Assessing the talent of faculty and attracting it with money is more complicated. And maybe irrelevant.

I would like to believe 1 but I don’t. I would like not to believe 3 but its hard. I do believe 2.

The French Open began on Sunday and if you are an avid fan like me the first thing you noticed is that the Tennis Channel has taken a deeper cut of the exclusive cable television broadcast in the United States. I don’t subscribe to the Tennis channel and until this year they have been only a slight nuisance, taking a few hours here and there and the doubles finals. But as I look over the TV schedule for the next two weeks I see signs of a sea change.

First of all, only the TC had the French Open on Memorial Day, yesterday. This I think was true last year as well, but now this year all of the early session live coverage for the entire tournament is exclusive on TC. ESPN2 takes over for the afternoon session and will broadcast early session games on tape.

This got me thinking about the economics of broadcasting rights. I poked around and discovered in fact that the TC owns all US cable broadcasting rights for the French Open many years to come. ESPN2 is subleasing those rights from TC for the segments they are airing. So that is interesting. Why is TC outbidding ESPN2 for the rights and then selling most of them back?

Two forces are at work here. First, ESPN2 as a general sports broadcaster has more valuable alternative uses for the air time and so their opportunity cost of airing the French Open is higher. But of course the other side is that ESPN2 can generate a larger audience just from spillovers and self-advertising than TC so their value for rights to the French Open is higher. One of these effects outweighs the other and so on net the French Open is more valuable to one of these two networks. Naively we should think that whoever that is would outbid the other and air the tournament. So what explains this hybrid arrangement?

My answer is that there is uncertainty about the TC’s ability to generate enough audience for a grand slam to make it more valuable for TC than for ESPN. In face of this TC wants a deal which allows it to experiment on a small scale and find out what it can do but also leaves it the option of selling back the rights if the news is bad. TC can manufacture such a deal by buying the exclusive rights. ESPN2 knows its net value for the French Open and will bid that value for the original rights. And if it loses the bidding it will always be willing to buy those rights at the same price on the secondary market from TC. TC will outbid ESPN2 because the value of the option is at least the resale price and in fact strictly higher if there is a chance that the news is good.

So, the fact that TC has steadily reduced the amount of time it is selling back to ESPN2 suggests that so far the news is looking good and there is a good chance that soon the TC will be the exclusive cable broadcaster for the French Open and maybe even other grand slams.

Bad news for me because in my area the TC is not broadcast in HD and so it is simply not worth the extra cost to subscribe. While we are on the subject, here is my French Open outlook

- Federer beat Nadal convincingly in Madrid last week. I expect them in the final and this could bode well for Federer.

- If there is anybody who will spoil that outcome it will be Verdasco who I believe is in Nadal’s half of the draw. The best match of the tournament will be Nadal-Verdasco if they meet.

- The Frenchmen are all fun but they don’t seem to have the staying power. Andy Murray lost a lot psychologically when he was crowing going into this year’s Australian and lost early.

- I always root for Tipsarevich. And against Roddick.

- All of the excitement on the women’s side from the past few years seems to have completely disappeared with the retirement of Henin, the injury to Sharapova and the meltdown of the Serbs. I expect a Williams-Williams yawner.

Following up on my previous post about the infield fly rule, lets get to the bottom of the zero-sum game that ensues when there is a fly ball in the infield. Let’s suppose the bases are loaded and there are no outs.

The infield fly rule is an artificial rule under which the batter is immediately called out and the runners are free to remain standing on base. Wikipedia recounts the usual rationale:

This rule was introduced in 1895 in response to infielders’ intentionally dropping pop-ups to get multiple outs by forcing out the runners on base, who were pinned near their bases while the ball was in the air.[2] For example, with runners on first and second and fewer than two outs, a pop fly is hit to the third baseman. He intentionally allows the fly ball to drop, picks it up, touches third and then throws to second for a double play. Without the Infield Fly Rule it would be an easy double play because both runners will tag up on their bases expecting the ball to be caught.

I would argue (as do commenters to my previous post) that there is no reason to prevent a double play from this situation, especially because it involves some strategic behavior by the defense and this is to be admired, not forbidden. But aren’t we jumping to conclusions here? Will the runners really just stand there and allow themselves to be doubled-up?

First of all, if there is going to be a double play, the offense can at least ensure that the runners remaining on base will be in scoring position. For example, suppose the runner on second runs to third base and stands there. And the batter runs to first base and stands there. The other runners stay put. Never mind that there will now be two runners standing on first and third base, this is not illegal per se. And in any case, the runner can stop just short of the base poised to step on it safely when the need arises. What can the defense do now?

If the ball is allowed to drop, there will be a force out of the runners on third and first. A double play. But the end result is runners on first and third. Better than runners on first and second which would result if the three runners stayed on their bases. And careful play is required by the defense. If the force is taken first at second base, then this nullifies the force on the remaining runners and the runner on third would be put out only by a run-down, a complicated play that demands execution by the defense. The runner could easily score in this situation.

If on the other hand the ball is caught, then the runer on second will be put out as he is off base. Another double play but again leaving runners on first and third.

So the offense can certainly do better than a simplistic analysis suggests. They could allow the double play but ensure that no matter what the defense does, they will be left with runners on first and third.

But, in fact they can do even better than that. The optimal strategy turns out to be even simpler and avoids the double play altogether. It is based on rule 7.08H: (I am referring to the official rules of Major League Baseball here, especially section 7)

A runner is out when … He passes a preceding runner before such runner is out

According to this rule, the batter can run to first base and stand there. All other base runners stay where they are. Now, a naive analysis suggestst that the fielder can get a triple play by allowing the ball to fall to the ground and using the force play at home, third, and second. But the offense needn’t allow this. The moment the ball touches the ground, the batter can advance toward second base, passing the runner who is standing on first and causing himself, the batter, to be called out. One out, and the only out because according to rule 7.08C, this nullifies the force so that all the baserunners can stay where they are, leaving the bases loaded:

if a following runner is put out on a force play, the force is removed and the runner must be tagged to be put out.

Given this option, the fielder can do no better than catch the ball, leaving the bases loaded. No double play. The same outcome as if the infield fly were called. So the designers of the infield fly rule were game theorists. They figured out what would happen with best play and they just cut to the chase.

But just because best play leads to this outcome doesnt mean that we shouldn’t require the players to play it out. When one team is heavily favored, we don’t call the game for the favorite just because we know that with best play they will win. To quote a famous baseball adage “that’s why they play the game.” The same should be true for infield flies. There’s a lot that both sides could get wrong.

As a final note, let me call your attention to the following, perhaps overlooked but clearly very important rule, rule 7.08I. I don’t think that the strategy I propose runs afoul of this rule, but before using the strategy a team should make certain of this. We cannot make a travesty of our national pastime:

7.08(i) A runner is out when … After he has acquired legal possession of a base, he runs the bases in reverse order for the purpose of confusing the defense or making a travesty of the game. The umpire shall immediately call “Time” and declare the runner out;

The first time I ever flew to Canada, I was flying to Toronto and I forgot to bring my passport. This was pre 9/11 and so the immigration authorities still had a sense of humor. Upon landing they brought me to the basement to interrogate me. Only one question was required and it was ingenious. “What is the infield fly rule?” Only an American would know the answer to this question. (The immigration authorities knew the right trade-off between Type I and Type II errors. A quick survey of my dinner companions tonight revealed that indeed only Americans knew the answer, but not all Americans.)

Suppose there is a runner on first base and the ball is hit in the air where it is catchable by an infielder. As the ball hangs in the air, it sets off a tiny zero sum game-within-the-game to be played by the players on the ground watching it fall to Earth. For if the ball is caught by the infielder, then the runner must be standing on first base, else he will be out after a quick throw to the first baseman, a double play. But, if he does stay standing on first base then the infielder can allow the ball to fall to the ground forcing the runner to advance. Then a quick throw to second base will get the runner out. And again a double play unless the batter has already made it to first.

Apparently this goes against some moral code deeply ingrained in American culture. Is it that the optimal strategy is random? Is it that we don’t want our heroes stranded between bases waiting to see which way they will meet their end? Is it that we don’t want to see the defense gaining advantage by purposefully dropping the ball? Whatever it is, we have ruled it out.

The infield fly rule states that in the above situation, the batter is immediately called out and the runner must stay on first base. No uncertainty, no inscrutability, no randomization. No intrigue. No fun.

But we are game theorists and we can still contemplate what would happen without the infield fly rule. Its actually not so bad for the runner. The runner should stand on first base. Usually by the time the ball descends, the batter will have made it to first base and a double play will be avoided as the infielder can either catch the ball and get the batter out or drop the ball and get the runner out. But not both.

In fact, if the ball is hit very high in the infield (usually the case since an infield fly almost always occurs because of a pop-up) the batter should advance to second base and even to third if he can. That is, run past the base runner, a strategy that otherwise would never be advisable. This forces the infielder to catch the ball as otherwise the best he can do is force out the runner on first, leaving a runner in scoring position.

So in these cases an infield fly does not really introduce any subtle strategy to the game. When the team at-bat plays an optimal strategy, the outcome entails no randomness. The final result is that there will be one out and a runner will remain on first base. And the fielder can always catch the ball to get the out.

However, this is not the only situation where the infield fly rule is in effect. It also applies when there are runners on first and second and also bases loaded. In those situations, if we did away with the infield fly rule the strategy would be a bit more subtle. And interesting! Lets try to figure out what would happen. Post your analysis in the comments.

(conversation with Roberto, Massimo, Itai, Alesandro, Wojciech, Alp, Stefan and Takashi acknowledged)

Next time: eliminating stalemate (another mysterious artificial rule) in Chess.

Update: Ah, a reader points out that the infield fly rule is waived when there is only a runner on first. Good thing my friendly immigration officer didnt know that! (even if he did, he would know that only an American would get the question wrong in that particular way).

Following up on Sandeep’s post about Alex Rodriguez’s alleged pitch-tipping, a game theorist is naturally led to ask a few questions. How is a tipping ring sustainable? If it is sustainable what is the efficient pitch-tipping scheme? Finally, how would we spot it in the data?

A cooperative pitch-tipping arrangement would be difficult, but not impossible to support. Just as with price-fixing and bid-rigging schemes, maintaining the collusive arrangement benefits the insiders as a group, but each individual member has an incentive to cheat on the deal if he can get away with it. Ensuring compliance involves the implicit understanding that cheaters will be excluded from future benefits, or maybe even punished.

What would make this hard to enforce in the case of pitch-tipping is that it would be hard to detail exactly what compliance means and therefore hard to reach any firm understanding of what behavior would and would not be tolerated. For example, if the game is not close but its still early innings is the deal on? What if the star pitcher is on the mound, maybe a friend of one of the colluders? Sometimes the shortstop might not be able to see the sign or he is not privy to an on-the-fly change in signs between the pitcher and catcher. If he tips the wrong pitch by mistake, will he be punished? If not, then he has an excuse to cheat on the deal.

These issues limit the scope of any pitch-tipping ring. There must be clearly identifiable circumstances under which the deal is on. Provided the colluders can reach an understanding of these bright-lines, they can enforce compliance.

There is not much to gain from pitch-tipping when the deal becomes active only in highly imbalanced games. But the most efficient ring will make the most of it. A deal between just two shortstops will benefit each only when their two teams meet. A rare occurrence. Each member of the group benefits if a shortstop from a heretofore unrepresented team is allowed in on the deal. Increasing the value of the deal has the added benefit of making exclusion more costly and so helps enforcement. So the most efficient ring will include the shortstop from every team. Another advantage of including a player from every team in the league is that it would make it harder to detect the pitch-tipping scheme in the data. If instead some team was excluded then it would be possible to see in the data that A-Rod hit worse on average against that team, controlling for other factors.

But it should stop there. There is no benefit to having a second player, say the second-baseman, from the same team on the deal. While the second-baseman would benefit, he would add nothing new to the rest of the ring and would be one more potential cheater that would have to be monitored.

How could a ring be detected in data? One test I already mentioned, but a sophisticated ring would avoid detection in that way. Another test would be to compare the performance of the shortstops with the left-fielders. But there is one smoking gun of any collusive deal: the punishments. As discussed above, when monitoring is not perfect, there will be times when it appears that a ring member has cheated and he will have to be punished. In the data this will show up as a downgrade in that player’s performance in those scenarios where the ring is active. And to distinguish this from a run-of-the-mill slump, one would look for downgrades in performance in the pitch-tipping scenarios (big lead by some team) which are not accompanied by downgrades in performance in the rest of the game (when it is close.)

The data are available.