You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘psychology’ tag.

When I read this (via Ryan Sager) about the classic good cop/bad cop negotiating ploy:

BUT there was also a twist we did not address in our research, and in fact, would have been tough to do as we were studying people in “the wilds” of organizational life. Their research shows that starting with a good cop and then using a bad cop was not effective, that the method only was effective for negotiating teams when the bad cop went first and the good cop followed. So, this may mean it really should be called “The Bad Cop, Good Cop Technique.”

it brought to mind some famous studies of Daniel Kahneman on perception and the timing of pleasure and pain. There is one you will never forget once you hear about it. Proctologists randomly varied the way in which they administered a standard colonoscopy procedure. Some patients received the usual treatment in which a camera was plunged into their rectum and then fished around for a few minutes. The fishing around is extremely uncomfortable.

An experimental group received a treatment which was identical except that at the very end <you can do better than that Beavis> the camera was left in situ <ok that’s pretty good> for an extra 20 seconds or so. The subjects were interviewed during the procedure and asked to report their level of pain, and after the procedure to report on the procedure overall. As intended, those in the experimental group reported that the final 20 seconds were less painful than the main part of the procedure. But the headline finding of the experiment was that those subjects receiving the longer treatment found the procedure overall to be more tolerable than the control group.

Or dead salmon?

By the end of the experiment, neuroscientist Craig Bennett and his colleagues at Dartmouth College could clearly discern in the scan of the salmon’s brain a beautiful, red-hot area of activity that lit up during emotional scenes.

An Atlantic salmon that responded to human emotions would have been an astounding discovery, guaranteeing publication in a top-tier journal and a life of scientific glory for the researchers. Except for one thing. The fish was dead.

Read here for a lengthy survey of the pitfalls of fMRI analysis. Via Mindhacks.

Auction sites are popping up all over the place with new ideas about how to attract bidders with the appearance of huge bargains. The latest format I have discovered is the “lowest unique bid” auction. It works like this. A car is on the auction block. Bidders can submit as many bids as they wish ranging from one penny possibly to some upper bound, in penny increments. The bids are sealed until the auction is over. The winning bid is the lowest among all unique bids. That is, if you bid 2 cents and nobody else bids 2 cents, but more than one person bid 1 cent, then you win the car for 2 cents.

In some cases you pay for each bid but in some cases bids are free and you pay only if you win. Here is a site with free bidding. An iPod shuffle sold for $0.04. Here is a site where you pay to bid. The top item up for sale is a new house. In that auction you pay ~$7 per bid and you are not allowed to bid more than $2,000. A house for no more than $2,000, what a deal!

I suppose the principle here is that people are attracted by these extreme bargains and ignore the rest of the distribution. So you want to find a format which has a high frequency of low winning bids. On this dimesion the lowest unique bid seems even better than penny auctions.

Caubeen curl: Antonio Merlo.

One of the least enjoyable tasks of a journal editor is to nag referees to send reports. Many things have been tried to induce timeliness and responsiveness. We give deadlines. We allow referees to specify their own deadlines. We use automated nag-mails. We even allow referees to opt-in to automated nag-mails (they do and then still ignore them.)

When time has dragged on and a referee is not responding it is typical to send a message saying something like “please let me know if you still plan to provide a report, otherwise i will try to do without it.” These are usually ignored.

A few years ago I tried something new and every time since then it has gotten an almost immediate response, even from referees who have ignored multiple previous nudges. I have suggested it to other editors I know and it works for them too. I have an intuition for why it works (and that’s why I tried it in the first place) but I can’t quite articulate it, perhaps you have ideas. Here is the clinching message:

Dear X

I would like to respond soon to the authors but it would help me a lot if I could have your report. I realize that you are very busy, so if you think you will be able to send me a report within the next week, then please let me know. If you don’t think you will be able to send a report, then there is no need to respond to this message.

From an excellent blog, Neuroskeptic, here is a survey of some data on mental illness incidence and suicide rates across countries. The correlation is surprisingly low:

So what’s the story? Take a look –

In short, there’s no correlation. The Pearson correlation (unweighted) r = 0.102, which is extremely low. As you can see, both mental illness and suicide rates vary greatly around the world, but there’s no relationship. Japan has the second highest suicide rate, but one of the lowest rates of mental illnesses. The USA has the highest rate of mental illness, but a fairly low suicide rate. Brazil has the second highest level of mental illness but the second lowest occurrence of suicide.

Perhaps I am reacting too much to the examples in the excerpt, but one possible explanation comes from noting that there is a difference between incidence of mental illness and detection. In countries where mental illness is readily diagnosed you will see more reports of it and also (assuming it does any good) less suicide. The US must be the prime example. And as I understand it, mental illness is highly stigmatized in Japan so the effect there is exactly what the data would suggest. I don’t know about Brazil.

Here’s my measure of creativity. Try it before reading on. Time yourself. Let’s say 30 seconds. You are going to think of 5 words. Your goal is to come up with 5 words that are as unrelated to one another as possible. Go.

Via Jonah Lehrer, I found this article that would give some backstory to my test. I will paraphrase, but it’s worth reading the article. First of all, our memory is understood to work by passive association (as opposed to conscious recollection.) You have a thought or an experience, and memory conjures up a bunch of potentially relevant stuff. Then, subconsciously, a filter is applied which sorts through these passive recollections and finds the ones that are most relevant and allows only these to bubble up into conscious processing.

Now, there are patients with damage to areas of their brain that effectively shuts off this filter. When you ask these patients a question, they will respond with information that is no more likely to be true as it is to be completely fabricated from related memories, or even previously imagined scenarios. These people are called confabulators.

The article discusses how especially creative people with perfectly healthy brains achieve their heights of creativity by reducing activity in that area of the brain associated with the filter. The suggestion is that creativity is the result of allowing into consciousness those ideas that less creative people would inhibit on the grounds of irrelevance. And this makes sense when you realize that thought does not “create” anything that wasn’t already buried in there somewhere. Observationally, what distinguishes a creative person from the rest of us is that the creative person says and does the unexpected, “outside the box,” “out of left-field” etc.

It reinforces the view that creative work doesn’t come from active “research.” At best you can facilitate its arrival.

You have a great need for other people to like and admire you. You have a tendency to be critical of yourself. You have a great deal of unused capacity which you have not turned to your advantage. While you have some personality weaknesses, you are generally able to compensate for them. Your sexual adjustment has presented problems for you. Disciplined and self-controlled outside, you tend to be worrisome and insecure inside. At times you have serious doubts as to whether you have made the right decision or done the right thing. You prefer a certain amount of change and variety and become dissatisfied when hemmed in by restrictions and limitations. You pride yourself as an independent thinker and do not accept others’ statements without satisfactory proof. You have found it unwise to be too frank in revealing yourself to others. At times you are extroverted, affable, sociable, while at other times you are introverted, wary, reserved. Some of your aspirations tend to be pretty unrealistic. Security is one of your major goals in life.

As the cliche goes, “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same.”

David Brooks has an excellent column on the way texting has influenced dating. It is based on an even more interesting article by Wesley Yang in New York magazine. The magazine has been posting sex diaries of New Yorkers online. There is a wealth of information and here is one snippet, a quote by a Diarist followed by an implication of his predicament:

12:32 p.m. I get three texts. One from each girl. E wants oral sex and tells me she loves me. A wants to go to a concert in Central Park. Y still wants to cook. This simultaneously excites me—three women want me!—and makes me feel odd.

This is a distinct shift in the way we experience the world, introducing the nagging urge to make each thing we do the single most satisfying thing we could possibly be doing at any moment. In the face of this enormous pressure, many of the Diarists stay home and masturbate.

Technology has taken paradoxes of choice to a new level of frequency but the essential idea remains unchanged. It is the paradox created by Buridan’s Ass – I should hasten to add that this is an animal not a body part. The poor Ass, faced with a choice of which of two haystacks to eat, cannot make up its mind and starves to death. The option the Ass “chose” may seem less pleasurable than the option that comes to hand to the diarists but the point is the same: a decision maker facing a wealth of great choices cannot make up his mind and ends up with a poorer default option.

The paradox has important implications for choice theory. I first learned about one possible implication from Amartya Sen many years ago. Sen’s point was that the revealed preference paradigm beloved of economists does not fare well in the Buridan’s Ass example. The Ass through his choice reveals that he prefers starvation over the haystacks and hence an observer should assign higher utility to it than the haystacks. Sen, if I remember correctly (grad school was a while ago!), says this interpretation is nonsense and an observer should take non-choice information into account when thinking about the Ass’s welfare.

A second interpretation is offered by Gul and Pesendorfer in their Case for Mindless Economics. Who are we to say what the Ass truly wants? To impute our own theory onto the Ass is patronizing. Maybe the Ass is making a mistake so its choices do not reflect its true welfare. But we can never truly know its preferences so we should forget about determining its welfare. This story works a little better with the masturbation scenario than the Buridan’s Ass example. This view is a work in progress with researchers trying to come up with welfare measures that work when decision makers commit errors.

So, we have no final answer and maybe we never will. Aristotle first discussed the paradox of choice the modern want-to-be-promiscuous texter faces. It is easy to give advice to all such asses (“make up your mind already!”) but if they continue to choose indecision how can we ever reach an unambiguous conclusion as to their welfare? The more things change, the more they stay the same.

I came across this simple theory of overoptimism recently (though it was published years ago). Suppose an agent has at least two actions from which to choose. An action gives either a payoff one or zero. For each, the agent has a subjective probability that the action gives a payoff of one. The probabilities of success are drawn independently from the same distribution G. Agent A then chooses one his actions, the one with the highest mean, according to his subjective beliefs. How do his beliefs about this action compare to those of an arbitrary observer?

Here’s where it gets interesting. The observer’s beliefs are different from agent A’s. They are drawn from the same distribution G but there is no reason that the observer’s beliefs are the same as agent A’s. In fact, the action agent A took will only be the best one from the observer’s perspective by accident. Actually, the observer’s beliefs will be the average of the distribution G which is lower than the belief of agent A since agent A deliberately took the action which he thought was the best. This implies that the agent A who took the action is “overoptimistic” relative to an arbitrary observer.

There are two further points. If there is just one action, this phenomenon does not arise. If agents have the same beliefs (a common prior), it also does not arise. So it relies on diverse beliefs and multiple actions. The paper is called “Rational Overoptimism and Other Biases” and is by Eric Van den Steen.

Swoopo.com has been called “the crack cocaine of auction sites.” Numerous bloggers have commented on its “penny auction” format wherein each successive bid has an immediate cost to the bidder (whether or not that bidder is the eventual winner) and also raises the final price by a penny. The anecdotal evidence is that, while sometimes auctions close at bargain prices, often the total cost to the winning bidder far exceeds the market price of the good up for sale. The usual diagnosis is that Swoopo bidders fall prey to sunk-cost fallacies: they keep bidding in a misguided attempt to recoup their (sunk) losses.

Do the high prices necessarily mean that penny auctions are a bad deal? And do the outcomes necessarily reveal that Swoopo bidders are irrational in some way? Toomas Hinnosaar has done an equilibrium analysis of penny auctions and related formats and he has shown that the huge volatility in prices is in fact implied by fully rational bidders who are not prone to any sunk-cost fallacy. In fact, it is precisely the sunk nature of swoopo bidding costs that leads a rational bidder to ignore them and to continue bidding if there remains a good chance of winning.

This effect is most dramatic in “free” auctions where the final price of the good is fixed (say at zero, why not?) Then bidding resembles a pure war of attrition: every bid costs a penny and whoever is the last standing gets the good for free. Losers go home with many fewer pennies. (By contrast to a war of attrition, you can sit on the sidelines as long as you want and jump in on the bidding at any time.) Toomas shows that when rational bidders bid according to equilibrium strategies in free auctions, the auction ends with positive probability at any point between zero bids and infinitely many bids.

So the volatility is exactly what you would expect from fully rational bidders. However, Toomas shows that there is a smoking gun in the data that shows that real-world swoopo bidders are not the fully rational players in his model. In any equilibrium, sellers cannot be making positive profits otherwise bidders are making losses on average. Rational bidders would not enter a competition which gives them losses on average.

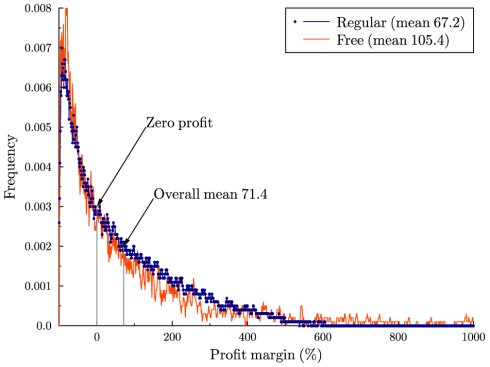

In the following graph you will see the actual distribution of seller profits from penny auctions and free auctions. The volatility matches the model very well but the average profit margin (as a percentage of the object’s value) is clearly positive in both cases. This could not happen in equilibrium.

An old paper by Akerlof modeled procrastination in a simple way. Suppose that doing a task today involves costs that are more salient today than the costs that would be incurred from doing the task tomorrow. (Hyperbolic discounting is the modern way of introducing this disparity.) And suppose you are naive in that you are bad at predicting your behavior in the future. Then every day you will make an optimal plan for when to do the costly task and every day your optimal plan will be to do it tomorrow. So it will never get done.

Unless there is a deadline. The day of the deadline you will know that the task will not get done tomorrow if you don’t do it today, so that is the day when you will finally do it. Ryan Sager describes an experiment with a similar finding. In fact the same effect holds with enjoyable tasks, not just pure costs. (Jennie and I never visited many of the tourist sites of San Francisco until a month before we moved away from the Bay Area.)

Take an experiment conducted by two marketing professors, Suzanne Shu and Ayelet Gneezy, set to be published in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Marketing Research (and written up in the May Atlantic by Virginia Postrel). Shu and Gneezy gave 64 undergraduates coupons for a slice of cake and a beverage at a local French pastry shop. Half got a certificate that expired in three weeks, half got one that expired in two months. While students were sure they were more likely to use the certificate with the more generous timeframe, the results were clear: The shorter timeframe made the students much more likely to redeem their certificates; 10 of the 32 students (31%) redeemed the three-week certificates, only two of the 32 students (6%) redeemed the two-month certificates.

You can imagine that the coupon is lost with some probability every day until it is used. Thus, the longer deadline means less chance of getting to the moment of truth. Here is a link to the original research.

abdominal pain, anorexia or/and weight loss, attention difficulties, burning or/and flushing, chest discomfort, chills, diarrhea, dizziness, dry mouth, dyspepsia, fatigue, heaviness, injection side reaction, insomnia, language difficulties, memory difficulties, nasal signs and symptoms, nausea, numbness, paresthesia or/and tingling, pharyngitis, somnolence or/and drowsiness, stinging or/and pressure sensation, taste disturbance, tinnitus, upper respiratory tract infection, vomiting, weakness

Most interestingly, the side effects of a sugar pill depend on what illness it is “treating.” And they resemble the side effects of the active medicine the placebo is standing in for. Mindhacks offers the most likely explanation.

One explanation may be that before taking part in a clinical trial, patients are informed of the possible side-effects that the active drug may cause, regardless of whether they are going to be given placebo or the actual medication.

Another is that getting better by itself has side effects. The theory would be that the body adjusts to the illness in certain ways and recovery is followed by undoing those adjustments, the physiological effects of which appear to be side-effects of the medicine.

Mindhacks discusses a surprising asymmetry. Journalists discussing sampling error almost always emphasize the possibility that the variable in question has been under-estimated.

For any individual study you can validly say that you think the estimate is too low, or indeed, too high, and give reasons for that… But when we look at reporting as a whole, it almost always says the condition is likely to be much more common than the estimate.

For example, have a look at the results of this Google search:

“the true number may be higher” 20,300 hits

“the true number may be lower” 3 hits

There are two parts to this. First, the reporter is trying to sell her story. So she is going to emphasize the direction of error that makes for the most interesting story. But that by itself doesn’t explain the asymmetry.

Let’s say we are talking about stories that report “condition X occurs Y% of the time.” There is always an equivalent way to say the same thing: “condition Z occurs (100-Y)% of the time” (Z is the negation of X.) If the selling point of the story is that X is more common than you might have thought, then the author could just as well say “The true frequency of Z may be lower” than the estimate.

So the big puzzle is why stories are always framed in one of two completely equivalent ways. I assume that a large part of this is

- News is usually about rare things/events.

- If you are writing about X and X is rare, then you make the story more interesting by pointing out that X might be less rare than the reader thought.

- It is more natural to frame a story about the rareness of X by saying “X is rare, but less rare than you think” rather than “the lack of X is common, but less common than you think.”

But the more I think about symmetry the less convinced I am by this argument. Anyway I am still amazed at the numbers from the google searches.

I wrote

If I am of average ability then the things I see people say and do should, on average, be within my capabilities. But most of the things I see people say and do are far beyond my capabilities. Therefore I am below average.

I am illustrating a fallacy of course, but it is one that I suspect is very common because it follows immediately from a fallacy that is known to be common. People don’t take into account selection effects. The people who get your attention are not average people. Who they are and what they say and do are subject to selection at many levels. First of all they were able to get your attention. Second, they are doing what they are best at which is typically not what you are best at. Also, they are almost always imitating or echoing somebody else who is even more talented and specialized so as to have gotten their attention.

Its healthy to recognize that you can be the world leader at being you even if you suck at everything else.

If I am of average ability then the things I see people say and do should, on average, be within my capabilities. But most of the things I see people say and do are far beyond my capabilities. Therefore I am below average.

Let’s say you read a big book about recycling because you want to make an informed decision about whether it really makes sense to recycle. The book is loaded with facts: some pro, some con. You read it all, weigh the pluses and minuses and come away strongly convinced that recycling is a good thing.

But you are human and you can only remember so many facts. You are also a good manager so you optimally allow yourself to forget all of the facts and just remember the bottom line that you were quite convinced that you should recycle.

This is a stylized version of how we set personal policies. We have experiences, collect data, engage in debate and then come to conclusions. We remember the conclusions but not always the reasons. In most cases this is perfectly rational. The details matter only insofar as they lead us to the conclusions so as long as we remember the conclusions, we can forget about the reasons.

It has consequences however. How do you incorporate new arguments? When your spouse presents arguments against recycling, the only response you have available is “yes, that’s true but still I know recycling is the right thing to do.” And you are not just being stubborn. You are optimally responding to your limited memory of the reasons you considered carefully in the past.

In fact, we are probably built with a heuristic that hard-wires this optimal memory management. Call it cognitive-dissonance, confirmatory-bias, whatever. It is an optimal response to memory constraints to set policies and then stubbornly stick to them.

Some research suggests that a child’s ability to delay gratification is a good predictor of achievement later in life. The research is based on some famous experiments in which children were left in a room alone with sweets and told that if they resisted until the experimenters returned, they would be rewarded with even more sweets. Via EatMeDaily here is a really cute video by Steve V of the marshmallow test.

If a drug trial reveals that patients receiving the drug did not get any healthier than those who took a placebo, is this a failure? It depends what the alternative treatment is. Implicitly its a failure if we believe that doctors will prescribe a placebo rather than the drug. Of course they don’t do that (often) but we can think of the placebo as representing the next-best alternative treatment.

But the right question is not whether the drug does better than the next-best alternative, but instead whether the drug plus the alternatives does better than just the alternatives. It could happen that the drug by itself does no better than placebo because the placebo effect is strong, but the drug offers an independent effect that is just as strong.

If so, then the right way to do placebo trials is to give one group a placebo and another group the placebo plus the drug being tested. The problem here is that the placebo group would know they are getting placebo which presumably diminishes its effect. So instead we use four groups: drug only, placebo only, drug plus placebo, two placebos.

Maybe this is done already.

Followup: Thanks to some great commenters I thought a little more about this. Here is another way to see the problem. Conceivably there may be a complementarity between the placebo effect (whatever causes it) and the physiological effect of the drug. The more you believe the drug will be effective the more effective it is. Standard placebo controls limit how much of this complementarity can be studied.

In particular, let p be the probability you think you are taking an effective drug. Your treatment can be summarized by your belief p and whether or not you get the drug. Standard placebo controls compare the treatment (p=0.5, yes) vs. (p=0.5, no). But what we really want to know is the comparison of (p=1, yes) and the next-best alternative. If there is a complementarity between the placebo effect and the physiological effect then (p=1, yes) is better than (p=0.5, yes).

“We have shown that by applying tools from neuroscience to the public-goods problem, we can get solutions that are significantly better than those that can be obtained without brain data,” says Antonio Rangel, associate professor of economics at Caltech and the paper’s principal investigator.

Here is the paper. You should read it. It is forthcoming in Science. Zuchetto Zip goes to Economists’ View.

The public goods aspect of the problem is not important for understanding the main result here, so here is a simplified way to think about it. You are secretly told a number (in the public goods game this number is your willingness to pay) and you are asked to report your number. You have a monetary incentive to lie and report a number that is lower than the one you were told. But now you are placed in a brain scanner and told that the brain scanner will collect information that will be fed into an algorithm that will try to guess your number. And if your report is different from the guess, you will be penalized.

The result is that subjects told the truth about their number. This is a big deal but it is important to know exactly what the contribution is here.

- The researchers have not found a way to read your mind and find out your number. Indeed, even under the highly controlled experimental conditions where the algorithm knows that your number is one of two possible numbers and after doing 50 treatments per subject and running regressions to improve the algorithm, the prediction made by the algorithm is scarcely better than a random guess. (See table S3)

- In that sense “brain data” is not playing any real role in getting subjects to tell the truth. Instead, it is the subjects’ belief that the scanner and algorithm will accurately predict their value which induces them to tell the truth. Indeed after conducting the experiment the researchers could have thrown away all of their brain data and just randomly given out payments and this would not have changed the result as long as the subjects were expecting the brain data to be used.

- The subjects were clearly mistaken about how good the algorithm would be at predicting their values.

- Therefore, brain scans as incentive mechanisms will have to wait until neuroscientists really come up with a way of reading numbers from your brain.

The full subtitle is “A Sober (But Hopeful) Appraisal” and its an article just published in the American Economic Journal: Microeconomics by Douglas Bernheim. The link is here (sorry its gated, I can’t find a free version.) Bernheim is the ideal author for such a critical review because he has one toe in but nine toes out of the emerging field of neuroeconomics. For the uninitiated, neuroeconomics is a rapidly growing but somewhat controversial subfield which aims to use brain science to enrich and inform traditional economic methodology.

The paper is quite comprehensive and worth a read. Also, check out the accompanying commentary by Gul-Pesendorfer, Rustichini, and Sobel. I may blog some more on it later, but today I want to say something about using neural data for normative economics. That’s a jargony way to say that some neuroeconomists see the potential for a way to use brain data to measure happiness (or whatever form of well-being economic policy is supposed to be creating.) If we can measure happiness, we can design better policies to achieve it.

Bernheim comes close to the critique I will spell out but goes in another direction when he discusses the identification problem of mapping neural observations to subjective well-being. I think there is a problem that cuts even deeper.

Suppose we can make perfect measurements of neural states and we want to say which states indicate that the subject is happy. How would we do that? Since neural states don’t come ready-made with labels, we need some independent measurement of well-being to correlate with. That is, we have to ask the subject. Let’s assume we make sufficiently many observations coupled with “are you happy now?” questions to identify exactly the happy states. What will we have accomplished then?

We will simply have catalogued and translated subjective welfare statements. And using this catalogue adds nothing new. Indeed if we later measure the subject’s neural state and after consulting the catalogue determine that he is happy, we will have done nothing more than recall that the last time he was in this state he told us he was happy. We could have saved the effort and just asked him again.

More generally, any way of relating neural data to well-being presupposes a pre-existing means of measuring well-being. Constructing a catalogue of correlations between these would only be useful if subsequently it were less costly to use neural measurements than the pre-existing method. It’s hard to imagine what could be more costly than phsyically reading the state of your brain.

A recent article in Wired about increases in the placebo effect over time has provoked much discussion. Here, for example, is a good counterpoint from Mindhacks.

But let’s assume that placebo is indeed a potentially effective treatment for psychological reasons. When you are a subject in a placebo-controlled study you are told that the drug you are taking is a placebo with probability p. Presumably, the magnitude of the placebo effect depends on p, with smaller p implying larger placebo effect.

This means there is a socially optimal p. That is, if doctors were to prescribe placebo as a part of standard practice, they should do so randomly and with the optimal probability p. Will they?

No, due to a problem akin to the Tragedy of the Commons. An individual doctor’s incentive to prescribe placebo is based on trading off the cost and benefits to his own patients. But the socially optimal placebo rate is based on a trade-off of the benefit to the individual patient versus the cost to the overall population. That cost arises because everytime a doctor gives placebo to his patient, this raises p and lowers the effectiveness of placebo to all patients.

So doctors will use placebo too often.

Phrenology was the attempt to correlate physical features of the brain and skull with personality, intellect, creativity. You got your data by plundering graves.

The three categories of individuals who were most interesting for finding out about the human mind were criminals, the insane, and geniuses, in the sense that they represented the extreme versions of the human mind …. It was easy enough to get the heads of criminals and the insane. Nobody wanted these, really. You could go to any asylum cemetery and root around and not be bothered, or hang out at the gallows and scoop up an executed criminal. Those two were pretty easy. Getting the heads of geniuses proved to be considerably more difficult.

Among the genius heads stolen and studied by phrenologists was Joseph Haydn’s.

What happens when you put someone in a dense forest, tell them to walk for an hour in a straight line and track them with GPS? They do this (top left.)

Their walking patterns were similar those of blindfolded walkers (right) and very different from those walking in a desert (bottom.) The results suggest that a good reference point (the sun in the case of the desert) helps. And the lack of a consistent turning direction rules out the hypothesis (believe it or not) that the tendency to walk in circles is due to asymmetrical leg lengths.

Read the article from Not Exactly Rocket Science.

Addendum: I bet that if they were swimming instead of walking you would see consistent circles.

I recently re-read Animal Farm. I think I last read it in secondary school in English class thirty (!) years ago. I still remember it (unlike Thomas Hardy’s The Woodlanders) because of the donkey character, Benjamin. The animals on the farm revolt and get rid of the farmer. They are led by the pigs. But the pigs are up to no good and are simply replacing the farmer with their own exploitative regime. They are very, very clever and can read and write. Benjamin is also clever and knows what the pigs are doing but he keeps quiet about it. The pigs succeed at huge cost to the other animals.

This is the thing I found mysterious and incomprehensible when I was twelve – why doesn’t the donkey reveal what the pigs are doing and save the other animals and the farm? This is the naivete of youth, believing if truth is simply spoken, it will be understood, appreciated and acted upon. Well, I was twelve. But I suppose (hope?) that many of us have these sorts of beliefs initially. As time passes, we act of these beliefs. Sometimes we succeed and sometimes we fail.

When we fail, we learn from our mistakes realizing what strategies do not work. Anyone who wants to influence collective decisions has to be subtle and know when to keep their mouth shut. This seems obvious now but presumably we learn it in school or in our family sometime when we see power trump reason. This learning process creates wisdom – you know more than before about strategies that fail. It also creates cynicism as you realize strategies with moral force have no political force. This is a sense in which cynicism is a form of wisdom. I didn’t understand Benjamin at all when I was twelve but now I see exactly why he was quiet. Orwell makes sure we understand the dilemma – Benjamin is alive at the end of the book unlike some animals who spoke out. I’m older and wiser.

What about successful strategies? The reverse logic applies to them. Success leads to optimism. A sophisticated learner should have contingent beliefs: some strategies he is optimistic about and some pessimistic. Someone more naive will have an average worldview. Whether it is cynical or not depends on the same issue that Jeff raised in his entry: are you overoptimistic at the beginning? If so, the failures will be more striking than the successes. This will tend to make you cynical.

Think of the big events that came out of nowhere and were so dramatic they captured our attention for days. 9/11, the space shuttle, the Kennedy assassination, Pearl Harbor. If you were there you remember exactly where you were.

All of these were bad news.

Now try to think of a comparable good news event. I can’t. The closest is the Moon landing and the first Moon walk. But it doesn’t fit because it was not a surprise. I can’t think of any unexpected joyful event on the order of the magnitude of these tragedies. On the other hand, it’s easy to imagine such an event. For example, if today it were announced that a cure for cancer has been discovered, then that would qualify. And equally significant turns have come to pass, but they always arrive gradually and we see them coming.

What explains this asymmetry?

1. Incentives. If you are planning something that will shake the Earth, then your incentives to give advance warning depend on whether you are planning something good or bad. Terrorism/assassination: keep it secret. Polio vaccine, public.

2. Morbid curiosity. There is no real asymmetry in the magnitude of good and bad events. We just naturally are drawn to the bad ones and so these are more memorable.

3. What’s good is idiosyncratic, we can all agree what is bad.

I think there is something to the first two but 1 can’t explain natural (ie not ingentionally man-made) disasters/miracles and 2 is too close to assuming the conclusion. I think 3 is just a restatement of the puzzle because the really good things are good for all.

I favor this one, suggested by my brother-in-law.

4 . Excessive optimism. There is no real asymmetry. But the good events appear less dramatic than the bad ones because we generally expect good things to happen. The bad events are a shock to our sense of entitlement.

Two related observations that I can’t help but attribute to #4. First, the asymmetry of movements in the stock market. The big swings that come out of the blue are crashes. The upward movements are part of the trend.

Second, Apollo 13. Like many of the most memorable good news events this was good news because it resolved some pending bad news. (When the stock market sees big upward swings they usually come shortly after the initial drop.) When our confidence has been shaken, we are in a position to be surprised by good news.

I thank Toni, Tom, and James for the conversation.

Jonah Lehrer writes an intriguing post about the primacy of tastes. He argues that the tastes we are wired to detect through our tongue are more strongly conditioned by evolution than tastes which rely more heavily on the olfactory dimension. As a result, foods that stimulate the receptors in our tongue require less elaborate preparations than foods that we appreciate for their aroma.

His leading example is ketchup vs. mustard.

So here’s my theory of why ketchup doesn’t benefit from fancy alternatives, while mustard does. Ketchup is a primal food of the tongue, relying on the essential triumvirate of sweet, sour and umami. As a result, nuance is unnecessary – I don’t want a chipotle ketchup, or a fancy organic version made with maple syrup. I just want the umami sweetness.

Mustards, in contrast, are foods of the nose, which is why we seek out more interesting versions. I like tarragon mustards, and dark beer mustards, and spicy brown mustards, because they give my sandwiches an interesting complexity. They give my nasal receptors something to sense.

This explains why the market shelves are stocked with countless varieties of mustard but all ketchups are basically the same.

Now what about mayonnaise? Its primary payload is fat (mayonnaise is emulsified vegetable oil.) We are strongly conditioned to desire fat in our diet and its attraction is just as primitive as the attraction to sugar and salt. And yet mayonnaise undergoes even more transformations than mustard does.

How does this relate to the fact that the desire for fat is not wired through taste buds, but rather through mouthfeel?

How do you cut the price of a status good?

Mr. Stuart is among the many consumers in this economy to reap the benefits of secret sales — whispered discounts and discreet price negotiations between customers and sales staff in the aisles of upscale chains. A time-worn strategy typically reserved for a store’s best customers, it has become more democratized as the recession drags on and retailers struggle to turn browsers into buyers.

Answer: you don’t, at least not publicly. Status goods have something like an upward sloping demand curve. The higher is the price, the more people are willing to pay for it. So the best way to increase sales is to maintian a high published price but secretly lower the price.

Of course, word gets out. (For example, articles are published in the New York Times and blogged about on Cheap Talk.) People are going to assign a small probability that you bought your Burberry for half the price, making you half as impressive. An alternative would be to lower the price by just a little, but to everybody. Then everybody is just a little less impressive.

So implicitly this pricing policy reveals that there is a difference in the elasticity of demand with respect to random price drops as opposed to their certainty equivalents. Somewhere some behavioral economists just found a new gig.

Most of classical economic theory is built on the foundation of revealed preference. The guiding principle is that, whatever is going on inside her head, an individual’s choices can be summarized as the optimal choice given a single, coherent, system of preferences. And as long as her choices are consistent with a few basic rationality postulates, axioms, this can be shown mathematically to be true.

Most of modern behavioral economics begins by observing that, oops, these axioms are fairly consistently violated. You might say that economists came to grips with this reality rather late. Indeed, just down the corridor there is a department which owes its very existence to that fact: the marketing department. Marketing research reveals counterexamples to revealed preference such as the attraction effect. Suppose that some people like calling plans with lots of free minutes but high fees (plan A) and others like plans with fewer free minutes but lower fees (plan B). If you add a plan C which is worse on both dimensions than plan A, suddenly everybody likes plan A over plan B because it looks so much better by comparison to plan C.

The compromise effect is another documented violation. Here, we add plan C which has even more free minutes and lower fees than B. Again, everyone starts to prefer B over A but now because B is a compromise between the extreme plans A and C.

Do we throw away all of economic theory becuase this basic foundation is creaking? No, there has been a flurry of research recently that is developing a replacement to revealed preference which posits not a single underlying preference, but a set of preferences and models individual choices as the outcome of some form of bargaining among these multiple motivations. Schizonomics.

Kfir Eliaz and Geoffrey de Clippel have a new paper using this approach which provides a multiple-motivation explanation for the attraction and compromise effects. Add this to papers by Feddersen and Sandroni, Rubinstein and Salant, Ambrus and Rosen, Manzini and Mariotti, and Masatilioglu-Nakajima-Ozbay and one could put together a really nice schizonomics reading list.

I enjoyed this article in the Boston Globe which surveys a variety of theories for the (mostly anectodal) tendency for the most vocal moralizers to be the most prone to vice. When you read an article like this you have to start with simple null hypothesis that, other things equal, making a person more concerned about moral behavior will make them inclined to act morally. Many of the stories in this article are tempting, mostly because we want to hate hypocrites, but ultimately don’t put up a good counterargument to this benchmark view. However the following excerpt is more subtle and in my opinion the most robust story offered.

When asked about the phenomenon of the hypocritical moralizer, psychologists will often point to “projection,” an idea inherited from Freud. What it means – and there is a large literature to back it up – is that if someone is fixated on a particular worry or goal, they assume that everyone else is driven by that same worry or goal. Someone who covets his neighbor’s wife, in other words, would tend, rightly or wrongly, to see wife-coveting as a widespread phenomenon, and if that person were a politician or preacher, he might spend a lot of his time spreading the word about the dangers of adultery.

Top chess players, until recently, held their own against even the most powerful chess playing computers. These machines could calculate far deeper than their human opponents and yet the humans claimed an advantage: intuition. A computer searches a huge number of positions and then finds the best. For an experienced human chess player, the good moves “suggest themselves.” How that is possible is presumably a very important mystery, but I wonder how one could demonstrate that qualitatively the thought process is different.

Having been somewhat obsessed recently with Scrabble, I thought of the following experiment. Suppose we write a computer program that tries to create words from scrabble tiles using a simple brute-force method. The computer has a database of words. It randomly combines letters and checks whether the result is in its database and outputs the most valuable word it can identify in a fixed length of time. Now consider a contest between to computers programmed in the same way which differ only in the size of their database, the first knowing a subset of the words known by the second. The task is to come up with the best word from a fixed number of tiles. Clearly the second would do better, but I am interested in how the advantage varies with the number of tiles. Presumably, the more tiles the greater the advantage.

I want to compare this with an analogous contest between a human and a computer to measure how much faster a superior human’s advantage increases in the number of tiles. Take a human scrabble player with a large vocabulary and have him play the same game against a fast computer with a small vocuabulary. My guess is that the human’s advantage (which could be negative for a small number of tiles) will increase in the number of tiles, and faster than the stronger computer’s advantage increased in the computer-vs-computer scenario.

Now there may be many reasons for this, but what I am trying to get at is this. With many tiles, brute-force search quickly plateaus in terms of effectiveness because the additional tiles act as noise making it harder for the computer to find a word in its database. But when humans construct words, the words “suggest themselves” and increasing the number of tiles facilitates this (or at least hinders it more slowly than it hinders brute-force.)