You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘psychology’ tag.

Liberal commentators bemoan the demise of the old John McCain they thought they knew and loved. Joe Klein wonders what happened to the guy who originally sponsored the Dream Act to allow children of illegal immigrants to become citizens. Think Progress points out that he is now supporting the tax cuts to the rich he vilified in 2000-2004. What has happened to John McCain? Have his preferences changed?

Liberal commentators bemoan the demise of the old John McCain they thought they knew and loved. Joe Klein wonders what happened to the guy who originally sponsored the Dream Act to allow children of illegal immigrants to become citizens. Think Progress points out that he is now supporting the tax cuts to the rich he vilified in 2000-2004. What has happened to John McCain? Have his preferences changed?

There is one obvious theory that seems to make his positions consistent: McCain had to run to the right to beat off a primary challenger in Arizona. But, as Joe Klein points out, “he recently won reelection and doesn’t have to pretend to be a troglodyte anymore.” So this theory is flawed.

There is another obvious theory. In this one, you have to identify an outcome a person supports or opposes not just by the policy itself but also by the the other person who supports it. So you have outcomes like “tax policy opposed by Obama,” “tax policy supported by Bush,” “tax policy supported by Obama,” “tax policy opposed by Bush” etc. Then, it is quite consistent for McCain to support a 35% tax on the rich when Bush opposes it but to oppose a 35% tax on the rich when Obama proposes it. Essentially, if McCain loses to someone in a Presidential election or primary he opposes their policies whatever they are.

A sophisticated model along these lines is offered by Gul and Pesendorfer. It allows one person’s preferences to depend on the “type” of the other person, e.g. is the opponent selfish or generous? In principle, this model allows us to determine whether a person is spiteful using choice data. McCain certainly has some behavior that is consistent with spitefulness. Is he ever generous? We would need to know his choices when facing someone he beat in a contest or someone he has never played. Or is he just plain mean? Joe Klein leans towards spite based on the available data:

“He’s a bitter man now, who can barely tolerate the fact that he lost to Barack Obama. But he lost for an obvious reason: his campaign proved him to be puerile and feckless, a politician who panicked when the heat was on during the financial collapse, a trigger-happy gambler who chose an incompetent for his vice president. He has made quite a show ever since of demonstrating his petulance and lack of grace.

What a guy.”

If choice with interdependent preferences can be utilized in empirical/experimental analyses, we can investigate the soul of homo economicus using the revealed preference paradigm.

Subjects were given a sugar pill. They were told it was a sugar pill. They were told that sugar pills are not medicine. And yet they had better outcomes than the control group who were not treated at all.

Edzard Ernst, a professor of complementary medicine at the University of Exeter, says, “This is an elegant study which suggests that the ritual of giving a patient a remedy is clinically effective, even if that patient has been told that the remedy is a placebo.” Kaptchuk himself says, “I suspect that just performing “the ritual of medicine” could have activated or primed self-healing mechanisms.” And Amir Raz, a neuroscientist who studies placebos at McGill University, adds, “Scientific reports make it clear, even if strange and counterintuitive, that receiving – rather than the actual content of – medical treatment can trigger and propel a healing process.”

Notably, the patients (apparently even the control group) were told about the psychology of the placebo effect.

They told the patients that “placebo pills, something like sugar pills, have been shown in rigorous clinical testing to produce significant mind-body self-healing processes.” And they explained: that “the placebo effect is powerful; the body can automatically respond to taking placebo pills like Pavlov’s dogs who salivated when they heard a bell; a positive attitude helps but is not necessary; and taking the pills faithfully is critical.”

There are many caveats and open questions, the full article is worth a read.

Islam forbids suicide. Of the world’s three Abrahamic faiths, “The Koran has the only scriptural prohibition against it,” said Robert Pape, a professor at the University of Chicago who specializes in the causes of suicide terrorism. The phrase suicide bomber itself is a Western conception, and a pretty foul one at that: an egregious misnomer in the eyes of Muslims, especially from the Middle East. For the Koran distinguishes between suicide and, as the book says, “the type of man who gives his life to earn the pleasure of Allah.” The latter is a courageous Fedayeen — a martyr. Suicide is a problem, but martyrdom is not.

From an article in the Boston Globe on the psychology of suicide bombers.

And sell them in January to take advantage of the January effect: the predictable increase in stock prices from December to January. Many explanations have been, the most prominent being a tax-motivated sell-off in December by investors trying to realize a capital loss before the end of the year. But here is a paper that demonstrates a large and significant january effect in simple laboratory auctions. Two identical auctions were conducted, one in December and one in January and the bidding was significantly higher in January.

In the first experimental test of the January effect, we find an economically large and statistically significant effect in two very different auction environments. Further, the experiments spanned three different calendar years, with one pair of auctions conducted in December 2003 and January 2004 and another pair of auctions conducted in December 2004 and January 2005. Even after controlling for a wide variety of auxiliary effects, we find the same result. The January effect is present in laboratory auctions, and the most plausible explanation is a psychological effect that makes people willing to pay higher prices in January than in December.

Sombrero swipe: Barking Up The Wrong Tree.

Why do we get more conservative (little ‘c’) as we get older? Trying out new things pays off less when there’s less time left to benefit from the upside. That’s a simple story based on declining patience.

But there’s another reason which could kick in at middle age when there is still plenty of life left to live. Think of life as a sequence of gambles presented to you. They come with labels: gamble A, gamble B, …, etc. Every time you get the chance to try gamble A its a draw from the same distribution and you get more information about gamble A.

Suppose your memory is limited. What you can remember is some list of gambles that you currently believe are worth taking. When you have the opportunity to take a gamble that is on the list, you take it. When you are presented with a gamble that is not on the list you have a decision to make. You could try it, and if it looks good you can put it on your list but then you have to drop something else from your list. Or you can pass.

As time goes on, even though you don’t remember everything you once tried and then removed from your list, you know that there must have been a lot of those. And so when you are presented with an option that is truly new, you have no way of knowing that and your best guess is that you have actually tried it before and discarded it. So you pass.

(drawing: Stuck In Your Head from f1me.)

But it certainly awaits a behavioral treatment. Why do auctioneers talk like they are calling a thoroughbred race?

They talk like that to hypnotize the bidders. Auctioneers don’t just talk fast—they chant in a rhythmic monotone so as to lull onlookers into a conditioned pattern of call and response, as if they were playing a game of “Simon says.” The speed is also intended to give the buyers a sense of urgency: Bid now or lose out. And it doesn’t hurt the bottom line, either. Auctioneers typically take home from 10 to 20 percent of the sale price. Selling more items in less time means they make more money.

We focused our analysis on twelve distinct types of touch that occurred when two or more players were in the midst of celebrating a positive play that helped their team (e.g., making a shot). These celebratory touches included fist bumps, high fives, chest bumps, leaping shoulder bumps, chest punches, head slaps, head grabs, low fives, high tens, full hugs, half hugs, and team huddles. On average, a player touched other teammates (M = 1.80, SD = 2.05) for a little less than two seconds during the game, or about one tenth of a second for every minute played.

That is the highlight from the paper “Tactile Communication, Cooperation, and Performance” which documents the connection between touching and success in the NBA. Controlling (I can’t vouch for how well) for variables like salary, preseason expectations, and early season success, the conclusion is: the more hugs in the first half of the season the more success in the second half.

As I was walking toward my locker at the gym I checked my pocket for the little card with the locker combination written on it. It wasn’t there. In a panic I tried to recall the combination. It was just 30 minutes ago that I had that combination in my head. But I couldn’t remember it. So I searched all of my pockets and finally felt the card in my back pocket. Panic over, I left the card in my pocket and kept walking, my mind quickly wandering to some random topic.

When I reached the locker, without thinking I opened it from memory without looking at the card.

I often have that sense that trying too hard makes it hard to remember something. There is even a physical feeling that comes with it. It’s like the brain seizes up and gets locked into a certain part of memory storage with no way of retracing steps back to neutral and starting the search over. After enough experience with this I sometimes notice the potential for panic before starting to search intensively for a memory that feels like its going to be hard to find. You have to pretend like you don’t really have something to remember. And most of all you have to make sure not to think of the thing that you are trying to remember because you know that if you do, the search will start by itself and get stuck. If you can do a little Zen breathing for a minute and let that feeling pass over, then you can safely start to think about it and recover the memory with ease.

At least that’s how I imagine it would work.

Drug addicts across the UK are being offered money to be sterilised by an American charity.

Project Prevention is offering to pay £200 to any drug user in London, Glasgow, Bristol, Leicester and parts of Wales who agrees to be operated on.

The first person in the UK to accept the cash is drug addict “John” from Leicester who says he “should never be a father”.

Probably everyone would agree that a better contract would be one that offers payment for regular use of contraception, rather than irreversible sterilization. Sterilization is probably a “second-best” because it is easier to monitor and enforce.

But it takes sides in the addict’s conflicting preferences over time. He is trading off money today versus children in the future. For some, that’s what makes it the right second-best. For others that’s what makes it exploitation.

Here is more.

Suppose I want to divide a pie between you and another person. It is known that the other person would get value from a fraction

of the pie (that is, each “unit” of pie is worth 1 to him), but your value is known only to you. You value a fraction

of the pie at

dollars but nobody but you knows what

is.

My goal is to allocate the pie efficiently. If both of you are selfish, then this means that I would like to give all the pie to him if and all the pie to you otherwise. And if you are selfish then I can’t get you to tell me the truth about

. You will always say it is larger than 1 in order to get the whole pie.

But what if you are inequity averse? Inequity aversion is a behavioral theory of preferences which is often used to explain non-selfish behavior that we see in experiments. If you are inequity averse your utility has a kink at the point where your total pie value equals his. When you have less than him you always like more pie both because you like pie and because you dislike the inequality. When you have more than him you are conflicted because you like more pie but you dislike having even more than he has.

In that case, my objective is more interesting than when you are selfish. If is not too much larger than 1, then both you and he want perfect equity. So that’s the efficient allocation. And to achieve that, I should give you less pie than he because you get more value per unit. And now as we consider variations in

, increases in

mean you should get even less! This continues until

is so much larger than 1 that your value for more pie outweighs your aversion to inequity, and now you want the whole pie (although he still wants equity.)

And its now much easier to get you to tell me the truth. You will always tell me the truth when your value of is in the range where perfect equity is the unique efficient outcome because that way you will get exactly what you want. Beyond that range you will again have an incentive to lie about

to get as much pie as possible.

So inequity aversion has a very clear implication for an experiment like this. If the experimenter is promising always to divide the pie equitably and is asking the subject to report his value of , then inequity averse subjects will do only two possible things: tell the truth, or exaggerate their value as much as possible. They will never understate their value.

I would be curious to see if there are any experiments like this.

Apart from a certain solitary activity, all other sensations caused by our own action are filtered out or muted by the brain so that we can focus on external stimuli. There is a famous experiment which demonstrates an unintended consequence of this otherwise useful system.

You and I stand before each other with hands extended. We are going to take turns pressing a finger onto the other’s palm. Each of us has been secretly instructed to each time try and match the force the other has applied in the previous turn.

But what actually happens is that we press down on each other progressively harder and harder at every turn. And at the end of the experiment each of us reports that we were following instructions and it was the other that was escalating the pressure. Indeed, the subjects in these experiments were asked to guess the instructions given to their counterpart and they guessed that the others were instructed to double the pressure.

What’s happening is that the brain magnifies the sensastion caused by the other’s pressing and mutes the sensation caused by our own. Thus, each of us underestimates the pressure when it is caused by our own action. (In a control experiment the force was mediated by a mechanical device –and not the finger directly– and there was no escalation.) So each subject believes he is following the instructions but in fact each is contributing equally to the escalating pressure.

You are invited to extrapolate this idea to all kinds of social interaction where you are being perfectly polite, reasonable, and accomodating, but he is being insensitive, abrasive, and stubborn.

Poker players know that the eyes never lie. Indeed your eyes almost always signal your intentions for the simple reason that you have to see what you intend to do.

This is an essential difference between communication with eye movement/eye contact and other forms of communication. The connection between what you know and what you say is entirely your choice and of course you will always use this freedom to your advantage. But what you are looking at and where your eyes move are inevitably linked.

Naturally your friends and enemies have learned, indeed evolved to exploit this connection. Even the tiniest changes in your gaze are detectable. As an example, think of the strange feeling of having a conversation with someone who has a lazy eye.

Given that Mother Nature reveals such a strong evolutionary advantage for reading another’s gaze the question then arises why we have not evolved to mask it from those who would take advantage? The answer must be that it would in fact not be to our advantage.

With any form of communication, sometimes you want to be truthful and other times you want to deceive. The physical link between your attention and your gaze means that, for this particular form of communication you can’t have it both ways. Outright deception being impossible, at best Nature could hide our gaze altogether, say by uniformly coloring the entire eye.

But she chose not to. By Nature’s revealed preference, this particular form of honesty is evolutionarily advantageous, at least on average.

You can subscribe to a service and receive calls reminding you that you are awesome (ht MR).

You can probably think of people who would buy this service thinking it will bolster their self-esteem. You might even imagine that you yourself would get a little boost from having someone call you personally and tell you that you rock. But you probably think that this is leveraging some kind of behavioral, kludgy, semi-rational wiring in your personality and that you would quickly get de-sensitized to it.

But I disagree. I think that it would be a valuable motivator even for the most hyper-rational among us. Because it’s not a trick at all but really just a way to preserve mindsets over time. Suppose I tell you about something great I did. Then later on, when I am about to take on some challenge, like let’s say I am about to give a big lecture to an intimidating audience, you call me and remind me of the great thing I did. And you add your own interpretation of why it was great and how it shows that I am awesome. I don’t need to believe anything about your motivations, your reminder restores my brain to the state it was in when I myself was thinking about how great I am and why. And if your added color convinces me that you honestly agree with me then all the better.

Simply “writing it down” or memorizing the state of mind is not a perfect substitute. At a very minimum this is simply based on cost-minimization. Someone else is doing the remembering for me and that is worth something. But it’s even more than that.

If you have been following me it will come as no surprise that I have no trouble at all remembering what an stupendous guy I am and all the super-amazing feats of astounding splendifery I have accomplished in my life. Yet even with that overflowing supply of memories of greatness, I still get nervous in the face of a challenge. When that happens I have my daughter repeat something she once said to me at a minor moment of greatness: “you’re so smart daddy.” The memory of that moment is imprinted on the sound of her voice. That sound hooks into the vivid edges of my direct experience of the event. Immediately it’s “oh yeah, that’s how it’s done” and my perspective on the situation is totally new. And yet on the surface all she is doing is duplicating a memory that I had in there already.

Daughters are great, and not just for fueling your ego, but they cost more than $40 a month. By comparison, Awesomeness Reminders look like a pretty good deal.

Each brain-damaged person got a wad of play money, and instructions to gamble on 20 rounds of coin tossing (heads-you-win/tails-you-lose, with some added twists). Other people who had no such brain lesions got the same money and the same gambling instructions.

The brain-damaged gamblers pretty consistently ended up with more money than their healthier-brained competitors. The researchers speculate that when “normal” gamblers encounter a run of unhappy coin-toss results, they get discouraged and become cautious – perhaps too cautious. Not so the people with brain-lesion-induced emotional disfunction. Encountering a run of bad luck, they plough on, undaunted. And then enjoy a relatively handsome payoff. At least sometimes.

This optical illusion appears on a street in West Vancouver. It is an experiment to see whether the image of a girl crossing the street will get drivers to slow down.

The pushback has been from groups who worry that drivers might react by braking or swerving and cause an accident. But that’s the short-run problem. Isn’t the bigger worry what happens in the long run when drivers no longer react when they see a child crossing the street?

For 15 years, the British bookmaker William Hill allowed bettors to wager on their own weight loss, often taking out full-page newspaper ads to publicize the bet. This was a clear opportunity for those looking to lose weight to make a commitment, with real teeth. Here is a paper by Nicholas Burger and John Lynham which analyzes the data.

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2, which shows that 80% of bettors lose their bets. Odds for the bets range from 5:1 to 50:1 and potential payoffs average $2332.9 The average daily weight loss that a bettor must achieve to win their bet is 0.39 lbs. In terms of reducing caloric intake to lose weight, this is equivalent to reducing daily consumption by two Starbucks hot chocolates. The first insight we draw from this market is that although bettors are aware of their need for commitment mechanisms, those in our sample are not particularly skilled at selecting the right mechanisms.10 Bettors go to great lengths to construct elaborate constraints on their behaviour, which are usually unsuccessful.

Women do much worse than men. Bets in which the winnings were committed to charity outperformed the average. Bets with a longer duration (Lose 2x pounds in 2T days rather than x pounds in T days) have longer odds, suggesting that the market understands time inconsistency.

Beanie barrage: barker.

Abdelbasset al-Megrahi. He was the Lockerbie bomber who was released from a Scottish prison because he had just a few weeks to live. As it turns out, he lived for a year and may live for many more.

The public outrage has an uncomfortable edge to it.

Clinton yesterday implied strongly that Megrahi’s release, and his continued survival long beyond the three months predicted by Scottish ministers, meant justice for the families of the dead had been denied.

Let’s get this straight. We agree on the following ranking of outcomes, from best to worst.

- Alive and in prison

- Alive 1 year after being released from prison.

- Dead 1 week after being released from prison.

But its easy to get confused because, conditional on learning that he was going to be alive 1 year later, we see that releasing him was a mistake. Because we assumed that he was going to die in a week so that 1 and 2 were not feasible. Now that we see that 1 was actually feasible we are outraged that he is alive. When we feel outraged that he is alive we start to think that means that we wish he was dead. But alive/dead is just the signal that we made a mistake. What we really wish is that we hadn’t made the mistake of setting him free.

I don’t mind rejection but a lot of people do.

When I want to ask someone to join me for a coffee or lunch I always send email. And its all about rejection even though I don’t mind rejection so much. The reason is that nobody can know for sure how I deal with rejection. And almost everybody hates to reject someone who might have their feelings hurt.

If I ask face-to-face I put my friend in an awkward position. Because every second she pauses to think about it is an incremental rejection. Because while the delay could be just because she is thinking about scheduling, it also could be that she is searching for excuses to get out of it.

These considerations combined with her good graces mean that she feels pressure to say yes and to say yes quickly. Even if she really does want to go. I would rather she have the opportunity to consider it fully and I would rather not make her feel uncomfortable.

Email adds some welcome noise to the transaction. It is never common knowledge exactly when she is able to read my email invitation. If she gets it right away she can comfortably consider the offer and her schedule and get back to me on her own time. And she knows that I know that… that I have no way of knowing how much time it took her to decide.

Game theorists can’t stop trashing email as a coordination device but that’s because we always think that common knowledge is desirable. But when psychology is involved it is more often that we want to destroy common knowledge.

Subjects in an experiment were shown pictures of people of the opposite sex and were asked to rate their attractiveness. Some subjects were first subliminally flashed pictures of their opposite-sex parent. For other subjects the pictures they were rating were actually a composite image made from pictures of the subject himself. Both of these induced higher attractiveness ratings.

Finally, in a third treatment the subjects were falsely (!) told that the images they were seeing were partly morphed from pictures of themselves. This reduced the attractiveness ratings.

Here is a link to the paper.

Here is the abstract from a paper by Matthew Pearson and Burkhard Schipper:

In an experiment using two-bidder first-price sealed bid auctions with symmetric independent private values, we collected information on the female participants’ menstrual cycles. We find that women bid significantly higher than men in their menstrual and premenstrual phase but do not bid significantly different in other phases of the menstrual cycle. We suggest an evolutionary hypothesis according to which women are genetically predisposed by hormones to generally behave more riskily during their fertile phase of their menstrual cycle in order to increase the probability of conception, quality of offspring, and genetic variety.

Believe it or not, this contributes to a growing literature.

This guy thinks so.

There it is: Zynga’s dirty technique for making its $500 million. It ropes players into the game with the promise that absolutely anyone can play. It will even float you coins the first time you run out, not unlike the casino that gives a high-roller luxury accommodations in anticipation of making back the house’s stake. It dangles the prospect of a bigger, prettier, better farm; as the game loads, you’re faced with idyllic images of well-off farms, not unlike the glossy ads for high-end residences. But it’s nearly impossible to get some of those goods without ponying up a buck or two here and there. When Zynga’s got a user base of 61 million digital farmers, it’s easy enough to make ends meet, to say the least.

The argument seems to be: it sucks your time, it gets your friends hooked too, it’s stupid. Like TV, reading blogs, talking on the phone, etc. I do recommend reading the article though because its a fine case study in how to try and substitute a logical argument in place of “Why do people have tastes that are so different from mine?” (Full disclosure: some people very close to me play Zynga games. I think Zynga games are really stupid.)

Ten Gallon Greeting: GeekPress.

Here is a theory of why placebos work. I don’t claim that it is original, it seems natural enough that I am surely not the first to suggest it. But I don’t think I have heard it before.

Getting better requires an investment by the body, by the immune system say. The investment is costly: it diverts resources in the body, and it is risky: it can succeed or fail. But the investment is complementary with externally induced conditions, i.e. medicine. Meaning that the probability of success is higher when the medicine is present.

Now the body has evolved to have a sense of when the risk is worth the cost, and only then does it undertake the investment. Being sick means either that the investment was tried and it failed or that the body decided it wasn’t worth taking the risk (yet! the body has evolved to understand option value.)

Giving a placebo tricks the body into thinking that conditions have changed such that the investment is now worth it. This is of course bad in that conditions have not changed and the body is tricked into taking an unfavorable gamble. Still, the gamble succeeds with positive probability (just too low a probability for it to be profitable on average) and in that case the patient gets better due to the placebo effect.

The empirical implication is that patients who receive placebos do get better with positive probability, but they also get worse with positive probability and they are worse off on average than patients who received no treatment at all (didn’t see any doctor, weren’t part of the study.) I don’t know if these types of controls are present in typical trials.

After a disaster happens the post-mortem investigation invariably turns up evidence of early warning signs that weren’t acted upon. There is a natural tendency for an observer to “second-guess,” to project his knowledge of what happened ex post into the information of the decision-maker ex ante. The effects are studied in this paper by Kristof Madarasz.

To illustrate the consequences of such exaggeration, consider a medical example. A radiologist recommends a treatment based on a noisy radiograph. Suppose radiologists differ in ability; the best ones hardly ever miss a tumor when its visible on the X-ray, bad ones often do. After the treatment is adopted, an evaluator reviews the case to learn about the radiologist’s competence. By observing outcomes, evaluators naturally have access to information that was not available ex-ante; in that interim medical outcomes are realized and new X-rays might have been ordered. A biased evaluator thinks as if such ex-post information had also been available ex-ante. A small tumor is typically difficult to spot on an initial X-ray, but once the location of a major tumor is known, all radiologists have a much betterchance of finding the small one on the original X-ray. In this manner, by projecting information, the evaluator becomes too surprised observing a failure and interprets success too much to be the norm. It follows that she underestimates the radiologistís competence on average.

The paper studies how a decision-maker who anticipates this effect practices “defensive” information production ex ante, for example being too quick to carry out additional tests that substitute for the evaluator’s information (a biopsy in the medical example) and too reluctant to carry out tests that magnify it.

A tip of the boss of the plains to Nageeb Ali.

Did you know that the number 4, spoken in Chinese, sounds very similar to the Chinese word for death? For that reason the number 4 is considered unlucky. (You may also know that the number 8 sounds like money and so it is considered lucky.) Well it is unlucky. Indeed, the 4th of the month is the peak day for death by cardiac arrest among Asian Americans. That is according to this study which I found via my new favorite blog, which I found via my always favorite Twitterer, nambupini.

I went through a long showdown with tendonitis of the hamstring. At its worst it was a constant source of discomfort that occupied at least a fraction of my attention at all times. I knew that I had to heal before I would get back my to usual smiling happy self. So I worked hard, stretching, walking, running: rehabilitating.

My hamstring doesn’t bother me much anymore. But you know what? Now that it no longer dominates the focus of my attention, I am reminded that my back hurts, as it always has. But I had completely forgotten about that for the last year or so because during that time it didn’t hurt.

So I am not the content, distraction-free person I expected to be. Now that I have solved the hamstring problem my current distractions draw my attention to the next health-related job: keep my back strong, flexible, and pain-free.

This is a version of the focusing illusion. People are motivated by expected psychological rewards that never come. The classic story is moving to California. People in Michigan declare that they would be much happier if they lived in California, but as it turns out people in California just about as miserable as people who still live in Michigan.

Pain and pleasure make up the compensation package in Nature’s incentive scheme. Our attention is focused on what needs to be done using the lure of pleasure and the avoidance of pain. And if it feels like she is repeatedly moving the goal posts, that may be all part of the plan according to a new paper by Arthur Robson and Larry Samuelson.

They model the way evolution shapes our preferences based on two constraints: a) there’s a limit to how happy or unhappy we can be and b) emotional states are noisy. Emotions will evolve into an optimal mechanism for guiding us to the best decisions. Following the pioneering research of Luis Rayo and Gary Becker, they show that the most effective way to motivate us within these constraints is to use extreme rewards and penalties. If we meet the target, even by just a little, we are maximally happy. If we fall short, we are miserable.

This is the seed of a focussing illusion. Because after I heal my hamstring Nature again needs the full range of emotions to motivate me to take care of my back. So after the briefest period of relief, she quickly resets me back to zero, threatening once again misery if I don’t attend to the next item on the list. If I move to California, I enjoy a fleeting glimpse of my sought-after paradise before she re-calibrates my utility function, so that now I have to learn to surf before she’ll give me another taste.

Sarcasm is a way of being nasty without leaving a paper trail.

If I say “No dear, of course I don’t mind waiting for you, in fact, sitting out here with the engine running is exactly how I planned to spend this whole afternoon” then the literal meaning of my words leaves me completely blameless despite their clearly understood venom.

This convention had to evolve. If it didn’t already exist it would be invented. A world without sarcasm would be out of equilibrium.

Because if sarcasm did not exist then I have the following arbitrage opportunity: I can have a private vindictive chuckle by giving my wife that nasty retort without her knowing I was being nasty. The dramatic irony of that is an added bonus.

That explains the invention of sarcasm. But it evolves from there. Once sarcasm comes into existence then the listener learns to recognize it. This blunts the effect but doesn’t remove it altogether. Because unless its someone who knows you very well, the listener may know that you are being sarcastic but it will not be common knowledge. She feels a little less embarrassment about the insult if there is a chance that you don’t know that she knows that you are insulting her, or if there was some higher-order uncertainty. If instead you had used plain language then the insult would be self-evident.

And even when its your spouse and she is very accustomed to your use of sarcasm, the convention still serves a purpose. Now you start to use the tone of your voice to add color to the sarcasm. You can say it in a way that actually softens the insult. “Dinner was delicious.” A smile helps.

But you can make it even more nasty too. Because once it becomes common knowledge that you are being sarcastic, the effect is like a piledriver. She is lifted for the briefest of moments by the literal words and then it’s an even bigger drop from there when she detects the sarcasm and knows that you know that she knows …. that you intentionally set the piledriver in motion.

Sarcasm could be modeled using the tools of psychological game theory.

Here’s an experiment you can do that will teach you something. Get a partner. Think of a famous song and clap out the melody of the song as you sing it in your head. You want your partner to be able to guess the song.

Out of ten tries how often do you think she will guess right? Well she will guess right a lot less than that. This is the illusion of transparency which is very nicely profiled in this post at You Are Not So Smart. We overestimate how easily our outward expressions communicate what is in our heads.

This should be an important element of behavioral game theory because game theory is all about guessing your partner’s intentions. As far as I know, biases in terms of estimates of others’ estimates of my strategy is untapped in behavioral game theory. Its effects should be easily testable by having players make predictions about others’ predictions before the play of a game.

There are games where I want my partner to know my intentions. For example I want my wife to know that I will be picking up coffee beans on the way home, so she doesn’t have to. Of course I can always tell her, but if I overestimate my transparency we might have too little communication and mis-coordinate.

Then there are games where I want to hide my intentions. In Rock-Scissors-Paper it shouldn’t matter. I might think that she knows I am going to play Rock, and so at the last minute I might switch to Scissors, but this doesn’t change my overall distribution of play.

It should matter a lot in a casual game of poker. If my opponent has a transparency illusion he will probably bluff less than he should out of fear that his bluffing is too easy to detect. So if I know about the transparency illusion I should expect my opponent on average to bluff less often.

But, if he is also aware of the transparency illusion and he has learned to correct for it, then this changes his behavior too. Because he knows that I am not sure whether he suffers from the illusion or not, and so by the previous paragraph he expects me to fold in the face of bluff. So he will bluff more often.

Now, knowing this, how often should I call his bets? What is the equilibrium when there is incomplete information about the degree of transparency illusion?

In a long game of course reputation effects come in. I want you to believe that I have a transparency illusion so I might bluff less early on.

Are prejudices magnified depending on the language being spoken? An experiment based on a standard Implicit Association Test suggests yes.

In an Implicit Association Test pairs of words appear in sequence on a screen. Subjects are asked to classify the relationship between the words and then the time taken to determine the association is recorded. In this experiment the word pairs consisted of one name, either Jewish or Arab, and one adjective, either complimentary or negative. The task was to identify these categories, i.e. (Jewish, good); (Jewish, bad); (Arab, good); (Arab, bad).

The subjects were Israeli Arabs who were fluent in both Hebrew and Arabic.

For this study, the bilingual Arab Israelis took the implicit association test in both languages Hebrew and Arabic to see if the language they were using affected their biases about the names. The Arab Israeli volunteers found it easier to associate Arab names with “good” trait words and Jewish names with “bad” trait words than Arab names with “bad” trait words and Jewish names with “good” trait words. But this effect was much stronger when the test was given in Arabic; in the Hebrew session, they showed less of a positive bias toward Arab names over Jewish names. “The language we speak can change the way we think about other people,” says Ward. The results are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

Nice. But this leaves open the possibility that, since Hebrew is the second language, all response times in the Hebrew treatment were increased simply making it harder to see the bias. I would still prefer a design like this one.

Balaclava bluster: Johnson.

You firmly believe that the sun will rise every morning. Then one day you awake and the sun does not rise. What are you to believe now? You have basically two alternatives. One is to go on believing that the sun will rise every morning by rationalizing today’s exception. There could have been a total eclipse this morning. Perhaps you are dreaming. The other choice is to conclude that you were wrong and the sun does not rise every morning.

The “rational” (i.e. Bayesian) reaction is to weigh your prior belief in the alternatives. Yes, to believe that you are dreaming despite many pinches, or to believe that a solar eclipse lasted all day would be to believe something near to absurdity, but given your almost-certainty that the sun would always rise we are already squarely in the exceptional territory of events with very low subjective probability. What matters is the relative proportion of that low total probability made up of the competing hypotheses: some crazy exception happened, or the sun in fact doesn’t always rise. It would be perfectly understandable, indeed rational if you find the first much more likely than the second. That is, even in the face of this contradictory evidence you hold firm to your belief that the sun rises and infer that something else truly unexpected happened.

Cognitive dissonance is a family of theories in psychology explaining how we grapple with contradictory thoughts. It has many branches, but a prominent one and perhaps the earliest, suggests that we irrationally discard information that is in conflict with our preconceived ideas. It began with a study by Leon Festinger. He was observing a cult who believed that the Earth was going to be destroyed on a certain date. When that date passed and the Earth was not destroyed, some members of the cult interpreted this as proof they were right because it was their faith that saved humanity. This was the leading example of cognitive dissonance.

My preamble about Bayesian inference shows that when we see people who are rigid in their beliefs and we conclude that they are irrationally ignoring information, it is in fact we who are jumping to a conclusion. All we can really say is that we disagree with their prior beliefs and in particular the strength of those beliefs. Somehow though it is much less satisfying to just disagree with someone than to say that they are acting irrationally in the face of clear evidence.

Now, watch this video, especially the part that starts at the 3:00 mark. When this guy experiences his moment of cognitive dissonance, what is the rational resolution?

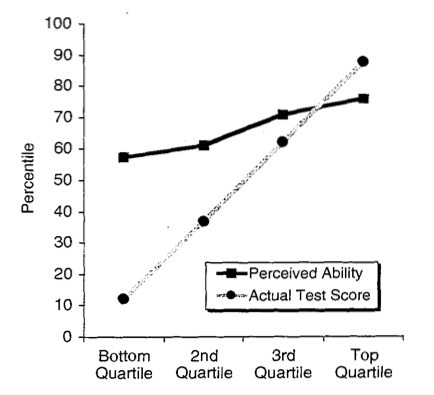

You have probably heard about the science that shows how incompetent people are overconfident. Here is a nice article which cuts through some of the hype and then presents a variety of ways to debunk the finding as a statistical illusion. (Which comes as a relief to me, but perhaps a little late.) Let me give you an even easier way, one that is related to the “regression toward the mean” idea given in the article. First, here is the finding summarized in a graph.

Suppose you have competent and incompetent people in equal proportions. They will take a test which will give them a score ranging from 0 to 4. The competent people score a 3 on average and they know this. The incompetent people score 1 on average and they know this. Due to idiosyncratic features of the test, the weather, etc. each subject’s actual score is random and it will range from one less to one more than their average.

You ask everyone to predict their outcome. The incompetent people predict a score of 1 and the competent people predict a score of 3. These are the best predictions. Then they take the test. The actual scores range from 0 to 4. Everyone who scored 0 predicted a score of 1, everyone who scored 4 predicted a score of 3, and the average prediction of those who scored 2 is about 2.

Trilby tribute: Marginal Revolution.