You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘economics’ category.

This issue is perplexing many of us who teach in business schools – are we going to have to change our classes as one of the firms in many of our key examples goes bankrupt?

We are not sure we have a good answer to our question so we will satisfy ourselves with a brain dump.

First, it may very well be true that, as CEO Reed Hastings is saying, Netflix does not want to end up like Borders or AOL in the garbage can of history when the next new technology comes along. After all, Blockbuster has never really recovered from missteps when Netflix DVDs arrived on the scene.

Therefore, Netflix wants to be ahead of the curve when DVD technology dies and everyone watches streaming movies. Here is one way to do this: keep the total price of 1 DVD at a time +streaming at $10 but price streaming alone at $6 and 1 DVD alone at $8. What they did instead, to maintain margins we assume, is raise prices by 60% so I DVD at a time + streaming is now $16. Of course this going to cause some serious fall in demand and also create a media frenzy.

There is a broader point: we gave one example of how Netflix might shuffle prices to create switching but we do not have the internal data on revenue and costs so the optimal pricing might be different. But whatever it is, the optimal pricing requires the DVD and streaming prices to be coordinated. If you split these two services into different (competing?) companies, you might create a price war and not only undermines your whole strategy but destroys your profits….

Even if completely separating the two businesses is the only way Netflix feels it can incentivize its streaming business to move ahead properly, there is absolutely no reason the company should expect consumers to care about its internal strategy issues – the strange angle taken by Hastings’ blog postings and emails to customers. It seems to us that it is the large price hike, far more than any other aspect, which has upset customers.

As a final comment, even if Netflix gets everything right operationally in its streaming business, it is hard to see how they plan to maintain margins and demand given that their suppliers (the content producers and owners) have a great deal of bargaining power and have every incentive to treat Netflix as only one outlet among many competing ones for their product. Other companies in the content delivery business, such as cable & satellite operators, face similar issues, but have the advantage of higher barriers to entry in terms of local franchise rights and physical infrastructure that gives them greater scope to raise prices……Our guess is that we will have more posts as more information arrives.

Sandeep Baliga and Peter Klibanoff

Many homeowners are taking advantage of low interest rates to refinance their mortgage. One group is conspicuously absent: low income homeowners with a history of shaky credit. Refinancing would help them and the economy at large but the costs of refinancing plus the reluctance of lenders to lend has compromised the availability of credit to this group. What is the solution? There are three proposals that are in the public domain.

1. Inflation: This has been proposed by Ken Rogoff. He would use inflation to reduce the value of debt and get borrowing moving again. The difficulty is that the FED has carefully nurtured a reputation as an inflation fighter for the last couple of decades. Once it loses that reputation can it recover in time for an inflationary period? This issue makes he Rogoff solution unpopular with many central bankers.

2. Loan Modification: Posner and Zingales propose a loan modification program. The details are complex but require some Congressional input to change bankruptcy law or pass new legislation. This is politically impossible in the current political climate so whatever the merits of the plan, it does not seem feasible.

3. Refinance: Boyce, Hubbard and Mayer propose to ease lending rules and offer loans at 4% to eligible homeowners whose loans are guaranteed by Fannie and Freddie. How much if this plan is implementable by the President without Congressional approval? That is the question. On first blush, this plan seems the most politically feasible to me.

The end of summer heralds the annual ritual of the suburban block party. The street has to be blocked off, notices have to be put up so no-one parks on the street, food has to be ordered or cooked etc. The burden falls on the people with kids because “The block party’s for the kids” we all say. Obviously, there is a huge free-rider problem – we can all enjoy the benefits of the block party without spending time on setting things up. If you don’t hang out with your neighbors much, “repeated game” effects are minor. Hence, morality and peer pressure must step in to provide incentives.

For example, suppose you sign up to put up notices warning people not to park on the street on the day of the block party. You write up some flyers and put them under car windscreen wipers. You print off notices and staple them to trees. You think you’ve done a pretty good job. The next day you wander round putting in new flyers

![photo[1]](https://cheaptalk.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/photo11.jpg?w=300&h=225) under car wipers and check on the notices. Mysteriously, someone has taken it upon themselves to put up their own notices. These are taped to the trees not stapled. Is that really superior? You are not sure but you see the implicit rebuke in the intervention. Homo economicus would revel in the intervention – he could slack off even more knowing someone will do his job for him. But homo normalicus feels a tad pissed off and even a bit guilty, even though no guilt is truly warranted. Next year, normalicus will go back to picking up the fried chicken from Jewel-Osco. But if economicus/evilicus pops out, he will do the same job worse out of rationality or spite.

under car wipers and check on the notices. Mysteriously, someone has taken it upon themselves to put up their own notices. These are taped to the trees not stapled. Is that really superior? You are not sure but you see the implicit rebuke in the intervention. Homo economicus would revel in the intervention – he could slack off even more knowing someone will do his job for him. But homo normalicus feels a tad pissed off and even a bit guilty, even though no guilt is truly warranted. Next year, normalicus will go back to picking up the fried chicken from Jewel-Osco. But if economicus/evilicus pops out, he will do the same job worse out of rationality or spite.

Suppose a firm can enter one of several markets. Other things equal, the fewer competitors there are, the greater is the incentive to enter as profits are decreasing in the number of competitors. So, smart managers should enter markets with fewer competitors. The deregulation of local telecommunications services in 1996 led to entry by competitive local exchange carriers (CLECs). These varied in the experience and education of senior managers and hence allow a descriptive and analytic analysis of entry decisions. Goldfarb and Xiao perform this analysis and find

Our descriptive analysis, which characterizes the entry decisions of facilities based CLECs in 234 midsize US markets with populations between 100,000 and 1,000,000 as of

the 2000 Census, reveals that experienced CEOs, CEOs with an economics or business

education, and CEOs who attended the most selective undergraduate institutions tended to enter

markets with fewer competitors.

They also estimate a behavioral model of entry to try to identify strategic sophistication as defined by the Cognitive Hierarchy model of Camerer, Crawford etc. They find that the firms with strategically sophisticated managers are more likely to survive and be profitable. There are many things that one might ague with - e.g. Doesn't better (economics/business) education help you to motivate workers better, cut costs etc? Why is strategic sophistication identified only with competition avoidance? Many questions come to mind but this is still an interesting paper.

In the thirteenth century, Italians and Dutch traders went to Champagne not to drink champagne but to trade. They had to travel there and back and worry about theft. There was always the chance that some dispute would arise at the trade fairs. Courts arose to enforce contracts. Did they arise spontaneously in Coasian fashion, created by contracting parties to facilitate trade? Or was their government intervention? The first view is advocated by Milgrom, North and Weingast in a lovely and influential paper. MNW invoke some “stylized facts” about the institution of the “Law Merchant”, They claim the law merchant was a kind of store of the history of past exchanges. The law merchant could substitute for the incomplete knowledge of trading parties themselves and had good incentives to be honest himself to retain his income as a law merchant. The paper is mainly theoretical and has a nice prisoner’s dilemma model with traders changing partners every period.

A new paper by Edwards and Ogilvie challenges the stylized facts that motivate MNW. They claim:

The policies of the counts of Champagne played a major role in the rise of the fairs. The counts had an interest in ensuring the success of the fairs, which brought in very

significant revenues. These revenues in turn enabled the counts to consolidate their political position by rewarding allies and attracting powerful vassals….The first institutional service provided by the counts of Champagne consisted of mechanisms for ensuring security of the persons and property rights of traders. The counts undertook early, focused and comprehensive action to ensure the safety of merchants travelling to and from the fairs..

A second institutional service provided by the rulers of Champagne was contract enforcement. The counts of Champagne operated a four-tiered system of public lawcourts which judged lawsuits and officially witnessed contracts with a view to subsequent enforcement…

A final reason for the success of the Champagne fair-cycle was that it offered an almost continuous market for merchandise and financial services throughout the year, like a great trading city, but without the most severe disadvantage of medieval cities – special privileges for locals that discriminated against foreign merchants

The paper is an interesting read and there are lots of rich details about the Champagne fairs themselves.

There are four major providers of national cellphone service in the U.S – Verizon, AT&T, Sprint and T-Mobile. Two of them are proposing to merge. What impact will the merger have on consumers? Senator Herbert Kohl (of Kohl’s stores fame) says:

“According to Consumer Reports, ‘T-Mobile plans typically cost $15 to $50 per month less than comparable plans from AT&T.” Removal of such a maverick price competitor from such a highly concentrated market – a competitor that disciplines price increases from all three other national cell phone competitors, not only At&T – raises a substantial likelihood that prices will rise following this merger.”

Someone can take the opposite view to ATT-TM LT to DOJ and FCC but at least it is coherently argued.

When the debt limit increase finally passed, the law included the creation of a 12 person committee, the SuperCongress, which will negotiate the next round of spending cuts and tax increases. If they fail to agree, automatic spending cuts go into effect. These spending cuts include elements that are painful to both parties and this punishment is meant to help the committee members compromise. Also, the automatic spending cuts that kick in if there is no compromise are not as painful for the economy as a failure to increase the debt limit. This seems to be the idea. I have a couple of points.

First, the Democrats partly caved this time around because they feared the Tea Party wing of the Republican House members were “crazy types” who were willing to destroy ratings of American Treasury bonds to get dramatic spending cuts. Next time around, the threat of disagreement has to police the Tea Partiers. Do they really care about defense? If they care about small government and less foreign intervention, they may actually want defense spending cuts. To get these guys to compromise, the disagreement point should have included libertarian-unfriendly policies. Federally mandated rules that everyone should brush their teeth twice a day, extra additives in drinking water, gun control laws and perhaps a constitutional amendment to eliminate the right to bear arms. Stuff like that should have been in the disagreement point.

Second, the parties face a choice of whom to put onto the SuperCongress. Each party will have six members, three drawn from each chamber. The strategic problem is fairly familiar as it resembles Schelling’s discussion of delegated bargaining. Each party has the incentive to appoint extreme members with tough bargaining stances so the other side will be more likely to give in. Paul Ryan is an obvious choices for the Republicans. Dick Durbin is an obvious choice for the Democrats. If both parties pursue this strategy, there will be deadlock and the disagreement point will come out of the SuperCongress (another example of Prisoner’s Dilemma everywhere).

This analysis is normative – it does not account for strategic errors. And there have been plenty of those. During the health care negotiations we had Max Baucus fruitlessly pursuing his Republican friends trying to get them to sign on. Olympia Snowe got a lot of one-one-one face time with the President. As Krugman points out (see also Jon Stewart a couple of nights ago!), the debt limit extension could have been folded into the extension of the Bush tax cuts last December but the President believed John Boehner at his word. So, my guess is that while Nancy Pelosi and the Republicans will follow the rational choice predictions because they are quite clearheaded, Harry Reid will try to forge a bipartisan compromise. Max Baucus is on (and Kent Conrad would have been if he were not retiring). Ben Nelson is a maybe. Why not go take the extra step Harry and nominate Susan Collins or Olympia Snowe to show that you mean well? With that kind of strategy, the Bush tax cuts may get extended again as part of the SuperCongress compromise and remarkably the Democrats might be forced to implement a compromise that is worse for them than the disagreement point.

Auctions on eBay have a deadline and aggressive bidding occurs just before the auctions ends. This is called “sniping” (see this excellent paper for a discussion along with the study of many other interesting issues). One reason offered for this behavior is that bids might not come in as the auction ends so if your low bid gets in and my high bid does not, you win anyway (I seem to remember a paper by Al Roth along these lines). A similar effect arises in the debt limit negotiations.

Assume for now the deadline is August 2 – if the debt limit is not raised by then all hell breaks loose. If the House has a proposal on the table later today, this gives the Senate the change to reject it and table their own proposal. But if the House gets their proposal in on August 1, there is too little time left for the Senate to respond with their own bill. If they reject the House proposal, all hell breaks loose. And if the President vetoes the bill, all hell breaks loose. So, there is distinct advantage to the House from delaying the vote. Symmetrically, there is similar advantage to the Senate from delaying the vote. But if both delay the vote, there is also a huge risk that neither proposal makes it through either chamber because both Reid and Boehner are having hard time drumming up enough votes. So, as both parties delay the vote, there is a huge chance of hell breaking loose….

What if the August 2 deadline is not hard? Then, I think I need a model to sort things out but my intuition is that there is bigger incentive to accept an early agreement (after August 1)- if you reject it, there is chance your counter proposal does not make it through as all hell breaks loose because the government runs out of money. But if early agreements might be accepted, there is a bigger incentive to move early and get your bid in…..

The gym which I hardly go to sends me frequent emails which may finally push me to cancel my membership. Here is one of the more interesting emails I got:

“We replace about 3,000 towels per month, and while roughly 10% of these are taken out of circulation by us because they are no longer suitable for use, the remaining 90% leave the building and don’t come back. 3,000 new towels a month, especially with the rapidly rising cost of cotton, adds up quickly to an amount of money that we should be spending on things like equipment upgrades and the provision of scholarships to our youth. Here are the steps we plan to take:

- Starting August 8th, two towels per visit will be available to any member who wants them at the Front Desk. This will be the only place where towels are available. The Y will reduce its buying to 1,500 towels a month. Our card scans at the Front Desk tell us this is enough to give everyone working out here two towels per visit.

- Buying will be capped at that 1,500 per month figure, so if towels are not returned we could run out and members working out later in the month would not be able to get towels. Returning your towels before leaving the Y will ensure that this does not happen.”

At first blush, it seems elementary economic theory predicts this plan will fail. The gym is using collective punishment to give incentives. If I take the towel home by mistake (they are too grotty to steal!), the chance of being pivotal in the towel service cancellation decision is small. So, while I’ll take a little bit more care to leave the towel, it’s not going to affect my incentives significantly. Everyone will think the same way and later on the month we will all be bringing our own towels to the gym.

Once we all stop going at the end of the month, as taking your own towel adds yet another impediment to gym attendance, the gym will get the dream member who does not turn up but pays the dues. Is this their dastardly plan after all?

Here is a possible solution: Everyone gets two towels when they turn in their gym ID at the front desk. They get the ID back if they return two towels when they leave. Otherwise they pay a fine. This does unfortunately create an incentive to steal a towel from someone else if you happen to lose your towel. But I think it’s still worth trying.

Researchers at RAND got hold of data on Al Qaeda in Iraq’s expenditures by sector. They also have data on attacks by sector. They claim:

[W]e find that for every $2,732 transmitted by the Anbar administrative emir to a particular sector, an additional attack occurred in that sector….We compute the $2,732 figure as follows. Each spending coefficient

shows how much a $1,000 change in spending in a given week would change the number of attacks. Using the coefficients in Table 5.3, increasing expenditures by $1,000 in a week would increase the number of attacks by 0.1 in the same week, by 0.08 one week later, by 0.08 two weeks later, by 0.04 three weeks later, and by 0.06 four weeks later, for a total of almost 0.4 additional attacks. To convert this to the additional expenditure needed for one complete attack, we divide $1,000 by 0.366 (the exact fractional increase in attacks) to get $2,732.

They add:

The amount $2,700 is equivalent to almost three times Anbari per capita 2007 household income (in 2006 dollars) and 40 percent of total average household income, a relatively large sum.

I assume the data cannot be shared. Otherwise, if the empirical analysis is sufficiently rigorous, the research is publishable in a peer-reviewed journal. These typically require data to be made publicly available so the analysis can be verified.

Entrepreneur Jay Goltz opines:

“If there is an aspect of running a small business that doesn’t get enough attention, I think it’s pricing.”

But it is hard and your salespeople can lead you astray:

“From my experience, many business owners do not do an analysis to calculate the effect a price increase might have on their bottom lines — again, for good reason. It is very difficult if not impossible to do. It’s more like guessing, perhaps an educated guess. I cannot tell you how to do it, but I can tell you what not to do. Do not rely on just your salespeople! Most will tell you that the sky will fall if you raise prices. They will tell you that customers are already complaining.”

Is it worth raising prices? The key variables are elasticty of demand and cost f production:

“Here’s the math: if you sell 100 widgets a week at $100 apiece and they cost you $65 apiece, you have a gross profit of $35 a widget or $3,500 a week. But because your fixed expenses have been rising and these are really good widgets, you decide you can charge $102 and still provide a good value to your customer. If you now sell only 95 widgets a week, you will have a gross profit of 95 x $37, or $3,515. But if you manage to sell 98, you will make $3,626. The point is that sales have to fall quite a bit for you not to come out ahead.”

He does not quite come out and say it but implicitly Goltz is comparing marginal revenue and marginal cost. In his examples, MR<MC so it makes sense to reduce output and increase prices.

Getting from the hotel to Heathrow, we faced the hold-up problem, a fitting end to a trip that began with the Grossman-Hart+25 conference in Brussels. Our cab driver was late picking us up and in compensation the cab company offered us a discount. But when we got to the airport, the cab driver refused to give us the discount saying he knew nothing about it and anyway it was not his fault as he’d been called after the previous driver bailed out. He refused to call his company to confirm my deal and refused to take a credit card (the hotel had told us the cab company would take a credit card if we paid a surcharge of five pounds).

Steam coming out of my ears, I traipsed into the airport and got cash out to pay him. This gave me time to think. The cab driver knew I was not a repeat customer but the cab company was contacted by my hotel and they were definitely hoping to keep the relationship with the hotel going into the future. So I called the hotel which called the cab company which called driver and I got my discount.

Deconstructing this later on, it seemed both I and the cab driver reacted irrationally. Conflict annoys me and the sum involved was trivial. The cab driver would definitely have lost his tip even if I had caved in to his demand so he would not have come out ahead by digging in his heels.

Finally, the cab company may not have set up incentives well with its (subcontracted?) employees. Their incentives are short term and differ from the company’s incentives which are long term. A salary or greater vertical integration rather than payment by commission might dominate. But if people are irrational, the design of the incentive scheme may not help. After all, as I said above, the tip should have provided incentives but it did not.

Counterfeiting money is the stuff of television, movies, and lore, but hardly seen by most of us – for only about one in ten thousand notes is found to be counterfeit annually. But long ago, it was a big deal – for instance, playing a major role in the Revolutionary and Civil Wars. And nowadays, while it only directly costs Americans about $60-$80 million a year, the Treasury acts as if it is a multibillion dollar potential crime. And of course, counterfeit checks is a major crime, and source of the Nigerian schemes that pepper our email spam boxes.

My coauthor, Elena Quercioli (visiting Bocconi, soon teaching at Central Michigan), experienced the reality of counterfeiting beyond our borders in Mexico City. A merchant once informed her that a few hundred dollars worth of pesos that she had just been issued at an ATM was all counterfeit. In the USA, she would have lost the money, and been questioned by police. But there, she retained her pesos, and proceeded to find a “greater fool” upon whom to unload her losses – the crime of “uttering” (which we are told is extremely hard to prosecute even in the USA).

Elena saw that her misadventure pointed to an interesting paper on counterfeit money that might atone for her mild transgressions. The small literature on this topic never modeled the costly vigilance choice of individuals in dealing with counterfeiting. She proceeded to convince the Secret Service to give her a data trove on counterfeit dollars. She pieced together a larger and hitherto partially unknown picture about the two flavors of counterfeit money – namely, seized money – that is confiscated from bad guys before it enters circulation – and passed money that is found at a later stage, and leads to losses by the public. Among her findings:

#1. The ratio of all counterfeit money to passed counterfeit money rises, but less than proportionately with the note.

#2. The per transaction passed rate (as a fraction of the circulation) is small for low notes, dramatically rises, and then levels off or drops. In Europe, for instance, the counterfeiting of the 500 Euro note is miniscule compared to the 200 Euro note.

(The Secret Service is under the mistaken impression that the $20 is the most counterfeit, as it fails to understand that the $50 and $100 notes circulate much less often. Go figure.)

#3. Since the 1970s, the ratio of all counterfeit money to passed counterfeit money has drammatically fallen about 90%.

#4. The fraction of counterfeit notes found by Federal Reserve Banks falls in the note.

I found these facts and intimations of a new theory very appealing. Our joint paper creates what may be the first multi-market “large game”, i.e. two interacting games each with a continuum of players. First, “bad guys” do battle with “good guys” in a massive game of cat and mouse. In it, good guys choose their vigilance effort and bad guys choose their counterfeit quality – where greater quality better frustrates counterfeiting efforts. Second, since some fake money inexorably passes into circulation, a collateral game is induced, this one pitting good guys against one another. Such a hot potato game is one of “strategic complements”: Fixing the counterfeiting rate, the more carefully I expect the next guy to examine his notes, the more carefully I must. We show that this second market fixes the counterfeiting rate.

The whole exercise has proved an exploration of nanoeconomics – for instance, we can deduce that individuals expend at most ¼ a cent of vigilance attention looking at the $100 note, and much less for lesser notes. I must say that the paper has reinforced my faith in economics. For despite such miniscule attention costs, the theory does a decent job of simultaneously explaining all the above patterns in counterfeiting – for instance, even the nonmonotone one emerges, that the passed rate rises and then falls. We even do a darn good job absolving the Secret Service of any incompetence in the plummeting seizure rates.

You went early to the Tower of London hoping to avoid the long line to gawk at the Crown Jewels. Many tour buses were on the same schedule. You went to the Science Museum on a Tuesday to avoid the weekend hordes. What you found were the weekday hordes of uniformed primary school children, pressing all the buttons on the interactive exhibits and leaving a trail of British germs for you to pick up. Anal, misanthropic, germaphobe though you are, of course you forgot the hand sanitizer.

You went early to the Tower of London hoping to avoid the long line to gawk at the Crown Jewels. Many tour buses were on the same schedule. You went to the Science Museum on a Tuesday to avoid the weekend hordes. What you found were the weekday hordes of uniformed primary school children, pressing all the buttons on the interactive exhibits and leaving a trail of British germs for you to pick up. Anal, misanthropic, germaphobe though you are, of course you forgot the hand sanitizer.

Under family pressure, you decide to go on a ride on the London Eye. The lines are going to be horrible. You go to their website and are pleasantly surprised. They must be private or have a non-London eye firmly trained on profit-maximization because they have come up with a price discrimination scheme exactly for last-minute-planning, people-hating, elitist b’stards like you. You have the option of Flexi Fast Track. You can turn up anytime and swan to the front of the queue!

The Science Museum is free (wow!) and publicly owned so they can’t pull a stunt like this (but why not Science Museum, you really should, you need the money!). The Queen is already so elitist that any further sign that there is a class system would cause a huge backlash. So, there is no two-track procedure for seeing the Crown Jewels. But the London Eye faces no such constraints. You can decide where you lie on the forward-planning/value-of-time dimensions and pick from several options. Why not go the whole hog and get drunk on the London Eye with a Pimm’s experience (with optional extra fee for second glass) or a wine tasting?

You may have one other quibble. Don’t expect to board like United Premier 1K travelers, before all the plebs come on with their crappy baggage. They will let in around ten of you Fast Track princes and ten of us plebs. But the Fast Track line is short because it is so bloody expensive (just like everything else in London!) and you will get on sooner. But you will be sharing a EyePod carriage with some plebs – get used to it. On United, you can recline in your b-class bed secure in the knowledge that the plebs like me in Economy can’t even come into your section to pee. But on the London Eye, you will be breathing the same air as me. Sorry.

With Oliver’s speech, we got some insights into the inception and inner workings of the Grossman-Hart team. It was formed when both were put into the same session at the Stanford theory conference. Sandy was working on informativeness of rational expectations equilibria and Oliver on general equilibrium with incomplete markets so their combination in one session was not natural. But they hit it off famously, despite political differences. In his speech, Sandy said he was a moderate and Oliver was extremely left-wing and, when it was his turn, Oliver said he was a moderate and Sandy was extremely right-wing.

The Grossman-Hart team met intermittently in the various locations where the two members were located, with Grossman being the more peripatetic of the two. They risked life and limb and went for long walks in the dodgy areas of Philadelphia and Chicago. On one visit, Sandy suggested two topics they might work on, the “theory of the firm” and “supply function equilibria”. Not sure what the latter amounted to, but Oliver suggested that he might have become an auction theorist if he had chosen the latter topic. Fatefully, he decided on the former topic. They went back and forth several times for around ten days, coming up with models and then throwing them out till they finally honed in on the model that made its way into JPE. They actually had a second model based on incomplete information but they decided to delete it from the final version (it was published in a book).

All this information comes from Oliver’s dinner speech. He went on to say that Sandy has affected his thinking in many other ways. He had tended to separate his economics from his political beliefs. Once when Grossman was visiting London to work with Hart, there was a strike of some sort. Oliver instinctively supported the strikers but, in debate with Sandy, Oliver eventually changed his mind. He began integrating his politics and his economics. (Parenthetically, this suggests that both of them see theory not just as a mental-master-of-your-own-domain exercise.) Oliver ended though by defiantly returning to his own moderate or left-wing tendencies, depending on your point of view. He said that while the National Heath Service is not first-best or even the fourth best, it is definitely better than the US version which is tenth best. He added that Sandy had enjoyed the dental care given by the NHS on a Cambridge visit when he had a toothache.

Grossman offered some final remarks. He had come up with the question “what is firm” in response to arguments made by ATT to avoid vertical disintegration. They argued that if a non-ATTphone were plugged into the ATT network it might cause its complete collapse. Hence, they argued that non-ATT phones should not be allowed for use on the ATT network. Grossman thought this argument was crazy and started wondering about the proper definition of the firm. He ended by discussing his toothache. While a root canal was considerably cheaper in England, Grossman complained that the area administered to by English dentists was still sore. QED?

(A Fuzzy iPhone Picture of Sandy Grossman)

One reason I came to the Grossman Hart + 25 conference was to catch a glimpse of Sandy Grossman and see what he had to say about his research. Grossman resigned from Wharton and has been running his own hedge fund for the last 25 years. I have never met him and my generation and younger know him only from his fearsome reputation. I did not get to speak to him so I cannot testify to his testiness. But some sense of his breadth came across.

He offered his current view on ownership and control which was typically idiosyncratic. He pointed out that human beings cannot will themselves to stop breathing. A safety mechanism overrides the conscious, deliberate decision hence an individual who has “decision-rights” over his body does not have “control rights”. And what holds at the level of the individual holds a fortiori at the level of the firm – the owner of an asset does not have necessarily have control rights. Apparently, in his spare time, Grossman reads about the working of the brain and also theoretical physics.

There is an infamous story about Grossman remodeling his house. Having worked on incomplete contracts, Grossman was extra careful to write a contract so there was no wiggle room for the contractor to hold him up. Inevitably, they fell into dispute. The judge said that with the contract that is normally signed he would have sided with homeowner in this kind of dispute. But since a non-standard and rather complex contract was written, the contingency under dispute must have been considered and dismissed. Hence, the judge found in favor of the builder. In other words, Grossman’s attempt to write a complete contract backfired and hurt him in the contract dispute.

When asked about his story, Grossman said “he had never heard it”. Via a Clintonesque use of wording, Grossman gave an incomplete answer and avoided the main thrust of the question …

- “I have given up. Letters have gone to both referees requesting the return of your manuscript to this office right away. I hope to God I can have better luck with the next people. I don’t know whether this is a matter of concern to you, but let me assure you that it is my intention not to publish the paper by Arrow and Debreu (which has also been submitted) before the publication of your paper (if both are found acceptable). I think this would only be fair to you.” – Econometrica Editor Robert Strotz’ 1953 letter to Lionel McKenzie on his existence proof for general equilibrium

- I had a fun conversation over dinner with Alessandro Lizzeri (outgoing AER coeditor) at the 2011 Winter Meetings in Denver. He had a fine insight about the economics graduate education: Economics grad students start out learning the classics in first year, absorb the stock of highlights from the last ten years in second year, and then start coming to field seminars, seeing the quasi-shitty flow of marginal new ideas … and we wonder why they are jaded.

- “Wanna see who lives in Einstein’s House now? Visit Princeton on Hallowe’en night ….. the current genius, Dr. Eric Maskin dresses up like Einstein and gives treats out to Princeton kids.”

- SOPHOMORE = SOPHOS + MOROS = “wise” + “foolish” (Greek)

- I just learned that (1) Thomas Crapper did not invent the toilet, and (2) the word “crap” does not come from his name. Now I feel totally disillusioned about my knowledge base. Bummer!

- My car takes 91 octane. Gas is sold locally in octanes 87, 89 and 92 or 93 octane. So I must average octanes. One would think that gas stations would have figured this arbitrage out. But it is always strictly more profitable for me to mix 92 and 87 octane than 92 and 89 octane. So drivers: avoid 89 octane!

- I am such a sucker for Venn diagrams. This one categorizing all drugs is for the ages.

Disclaimer: For me, caffeine is a stimulant and alcohol is a depressant (my nightly glass of red wine, angel face). I have had nitrous oxide (hallucinogen & depressant) two or three times. I have fended off the peer pressure to consume all others – does that make me a geek or a nerd? Curiously, cannabis – or marijuana (Mary Jane) – is simultaneously a stimulant, hallucinogen, depressant, & anti-psychotic.

- Jerry Seinfeld (September 1993) clearly beat Laibson (1994) to the punch on (the rebirth of) present-biased preferences, the conflict between future and current selves, and the value of commitment:

The Glasses I never get enough sleep. I stay up late at night, cause I’m Night Guy. Night Guy wants to stay up late. ‘What about getting up after five hours sleep?’, oh that’s Morning Guy’s problem. That’s not my problem, I’m Night Guy. I stay up as late as I want. So you get up in the morning, you’re … , you’re exhausted, groggy, oooh I hate that Night Guy! See, Night Guy always screws Morning Guy. There’s nothing Morning Guy can do. The only Morning Guy can do is try and oversleep often enough so that Day Guy loses his job and Night Guy has no money to go out anymore.Hey we can’t let Jerry beat us, so let’s credit this agenda to its rightful originator, Strotz (1956), before his fourteen year presidency of Northwestern.

- Gary Becker (1973) only barely edged out Sylvester Stallone (1976) on the importance of strategic complements in the marriage model. Sly had has this wonderful metaphor in Rocky: “I dunno, she’s got gaps, I got gaps, together we fill gaps.”

- Patrick Billingsley – who taught me convergence of probability measures at Chicago — was also a part-time actor. I was unaware he was a bailiff in “The Untouchables” (with Kevin Costner, Sean Connery, and Robert De Niro). His Probability and Measure textbook was his chef d’oeuvre. I find it cool that a world-renowned star of probability pursued his passion as an obscure actor.

- Why won’t the Happy Days owners release season 5 and later on dvd? After all, I have been waiting over two years to get past season 4. For the uninitiated, this is the season in which the TV series gave us the timeless metaphorical image to “jump the shark”. Perhaps they do not want to reveal this moment of futility?PS Which research agendas in the profession have also “jumped the shark”. ^_^ And could it be that their ratings (citations) decline long after their fundamentals do?

As a theorist, I can muse about empirical issues generally safe from the fear that I might seriously explore them. Next summer is another Olympic year of competition and commentary. Consider the 100M dash. Victory spells fame and fortune, second place historical obscurity. Effort expended is real, and competitors can roughly see how their nearest rivals are doing in real time, although admittedly in a bit of a blur. To what extent then can we understand behavior in these races using auction theory? If we regress winning times on times of predecessors, is the second fastest time the best predictor, and does it obviate the power in the other order statistics? And is this more true in the 10,000M run, where events are less of a blur, or less true, because at some point the race is often a foregone conclusion?

Another prediction of auction theory is that the best times should be more clustered in head to head race, for instance, than if we just asked runners to race alone, not knowing their rivals’ times, and then picked the fastest time.

In the early 1970s, Gary Becker was hitting stride, knocking out economic theories of crime, the allocation of time, discrimination, marriage, and children in rapid succession. His theory of marriage treated the marriage scene like any other economic market, cleared by a price. Men bid for women, and women bid for men. In a shallow view of his model, women sought handsome men, and men beautiful women, and beauty was not in the eye of the beholder. Becker’s main theorem — whose proof he credits to my esteemed colleague Buz Brock — found that the men and women efficiently sorted by their beauty when their beauties were complements.

I visited the Cowles Foundation at Yale for the winter of 2006, and taught a senior elective course. Seven fortunate students took my seminar in information economics. One impressive woman student — who organized the gay and lesbian social scene — asked whether the shallow view of Becker’s model was so unrealistic. Did babes match with hunks?

We brainstormed on data sources and settled on two new web sites: facebook.com and hotornot.com. Facebook allowed users to indicate with whom they were “in a relationship with”. Facebook was still new, and not yet open to all email addresses. So the student asked her friends at various campuses across America for their logins. And so began our stealth project. Hundreds of photos of matched men and women were downloaded, and then uploaded to HotOrNot, all on the sly. HotOrNot afforded us the average evaluation of about 200 women for every man, and 2000 men for every woman.

The result: Regressing straight men’s or women’s hotness on their partner’s hotness gave a highly significant fit, with a slope of about 0.7 — so that a man rising in hotness from 7 to 8 expects his partner to rise by 0.7 points. But sorting was far closer for gays and lesbians, with a slope for each of about 0.9. As Becker implied, beauty is income in this meat market, and the “richest” men match with the “richest” women.

Kellogg is raising money for a new building. The Dean and the Great and the Good and doing fundraising. Various committees are in charge of deciding how people should be allocated to offices. Given by lack of political acumen and seniority, I know I will be next to the men’s restroom in the basement. The absence of amy ambiguity about the outcome means I am spending no time agonizing about my decision. But I imagine many of my colleagues are looking at proposed plans and wondering if they can get the corner office. Or will they prefer to be close to friends and co-authors at the cost of giving up a great view of the lake and fit young undergrads playing soccer on the lakeside fields?

Last week’s economic theory seminar speaker, Mariagiovanna Baccara, has a paper with several co-authors that offers an answer. The paper documents the experience of the faculty at an unnamed (but easily guessable) professional school which moved into a new building. The school decided to use a random serial dictatorship mechanism: the professors were split into four equivalence classes by rank (full professors, assistant etc.). Within each class, the order in which each player could choose an office was determined randomly. If there are no externalities, this mechanism achieves an efficient allocation. The first player to move gets the penthouse suite, the second player, the next best corner office etc. But if players care about which players they end up next to, the procedure is not efficient. Each player will not fully internalize the effects of his choice on others.

Before the move, the professors sat within departments and small clusters of like-minded fellow researchers. If the value of this and other networks is small, we would expect players to choose the “room with a view” strategy, picking the best physical location from the remaining offices. The authors compare the allocation that would have resulted if faculty chose offices based on physical characteristics alone with the allocation that actually arose. They find, for example, that co-authors are 36% more likely to be together in the actual allocation that the simulated allocations.

It is possible to estimate network effects a bit better. Aware of the possible inefficiencies of their mechanism, the designers relied on the Coase Theorem to help them out: The mechanism allowed faculty to exchange offices in exchange for cash from their research accounts. If arbitrary exchanges are implemented say between 10 faculty, then ex post exchange will achieve the surplus maximizing allocation. The initial allocation determined via the dictatorship will simply determine the status quo from which bargaining begins but not the final allocation: the famous idea of property right neutrality. But large scale exchanges involve transactions costs and there were few exchanges observed and the ones observed involved two professors. So the authors look at pairwise stable allocations. Combined with various separability assumptions on preferences, this equilibrium notion allows them to estimate network effects. They find co-authorship is more important than department affiliation and friendship. Once these effects are estimated and utilities identified, we can ask the value left on the table by pairwise stable allocations. The authors find an allocation that gives a 183% increases in utility compared to the implemented allocation.

As other schools move buildings, they will use other mechanisms. It will be interesting to study their experience.

You’ve seen Thor, are about to go to the X Men prequel and are waiting to see Captain America. But where is Superman?

It turns out that a copyright issue has bedevilled the Superman character for many years. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster signed away rights to the Superman character to DC comics for $130 over seventy years ago. As the character literally and figuratively took off in the movies and in comic books, Siegel and Shuster got little share in the revenue. But the Copyright Act of 1976 allowed the original owners and their heirs to reclaim ownership if it turned out the value of their invention had become clearer over time and they had been underpaid. Siegel’s heirs used the law to eventually achieve joint ownership in 2008. Since then, investment in the Superman character has languished.

The reasons are simple and are related to the classic hold-up model of Grossman-Hart. Any gain from investment in Superman made by DC Comics will have to be shared with the Siegel heirs. This acts like a tax on investment and hence generates underinvestment. It is better of the ownership is in just one hand. But this amplifies the hold-up problem – it is obvious that DC Comics should own the rights to Superman. After all, they have the expertise in the comic book business and in the brand extensions. But how will they decide the price they will pay the Siegels to get 100% ownership? The present discounted value of the franchise going forward will be the key determinant. Hence, DC Comics (Warner Bros is also involved) have the incentive to destroy the value of the franchise to get a good price. Fans lament that this is what is happening:

Perhaps the most damning part of the decision document was the revelation that executives at Warners shared fans’ cynicism about Superman’s potential (Remember, Warners and DC were the defendants in this case):

Defendants’ film industry expert witness, Mr. [John] Gumpert, termed Superman as “damaged goods,” a character so “uncool” as to be considered passe, an opinion echoed by Warner Bros. business affairs executive, Steven Spira… Indeed, Mr. [Alan] Horn [Warner Bros. President] admitted to being “daunted” by the fact that the 1987 theatrical release of Superman IV had generated around $15 million domestic box office, raising the specter of the “franchise [having] played out.”

Almost as surreally, DC and Warners apparently argued to the court that

Superman was equivalent [in terms of public recognition and financial value] to a low-tier comic book character that appeared mostly on radio during the 1930s and 1940s and that has not been seen since a brief television show in the mid-1960s (the Green Hornet); an early 20th century series of books (Tarzan) or a 1930s series of pulp stories (Conan) later intermittently made into comic books and films; or a television, radio, and comic book character from the 1940s and 1950s, much beloved by my father, that long ago rode off into the proverbial sunset with little-to-no exploitation in film or television for decades (The Lone Ranger).

And these are the people in charge of the character?!?

(Hat Tip: Scott Ashworth)

In the New Yorker, Lawrence Wright discusses a meeting with Hamid Gul, the former head of the Pakistani secret service I.S.I. In his time as head, Gul channeled the bulk of American aid in a particular direction:

I asked Gul why, during the Afghan jihad, he had favored Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, one of the seven warlords who had been designated to receive American assistance in the fight against the Soviets. Hekmatyar was the most brutal member of the group, but, crucially, he was a Pashtun, like Gul.

But

Gul offered a more principled rationale for his choice: “I went to each of the seven, you see, and I asked them, ‘I know you are the strongest, but who is No. 2?’ ” He formed a tight, smug smile. “They all said Hekmatyar.”

Gul’s mechanism is something like the following: Each player is allowed to cast a vote for everyone but himself. The warlord who gets the most votes gets a disproportionate amount of U.S. aid.

By not allowing a warlord to vote for himself, Gul eliminates the warlord’s obvious incentive to push his own candidacy to extract U.S. aid. Such a mechanism would yield no information. With this strategy unavailable, each player must decide how to cast a vote for the others. Voting mechanisms have multiple equilibria but let us look at a “natural” one where a player conditions on the event that his vote is decisive (i.e. his vote can send the collective decision one way or the other). In this scenario, each player must decide how the allocation of U.S. aid to the player he votes for feeds back to him. Therefore, he will vote for the player who will use the money to take an action that most helps him, the voter. If fighting Soviets is such an action, he will vote for the strongest player. If instead he is worried that the money will be used to buy weapons and soldiers to attack other warlords, he will vote for the weakest warlord.

So, Gul’s mechanism does aggregate information in some circumstances even if, as Wright intimates, Gul is simply supporting a fellow Pashtun.

The new iPad “newspaper” the Daily profiles Next Restaurant and their fixed-price online reservation system. As we blogged before, the tickets sell out in seconds and there is a huge resale market with $85 tickets selling for thousands of dollars in the resale market. The excess demand implies the tickets are underpriced from a pure profit-maximization perspective. But Nick Kokonas, one of the partners in Next and the person responsible for the innovative pricing scheme, is reluctant to use an auction to capture the surplus Next is generating for scalpers. He is worried about price-gauging. We have suggested one solution: impose a maximum price/ticket, say $150.

There is a new idea reported in the Daily: Next will offer “season tickets” in 2012, allowing dinners to come four times/year, each time the restaurant changes theme, going from say French early twentieth century to South Indian mid-twentieth century (just a suggestion!). The usual motivation for season tickets is to offer a “volume discount” and extract more surplus from high willing to pay customers. Another is to have demand tied in. Next has no need to offer volume discounts, if anything the tables are priced too cheap. Perhaps there will be a volume premium for guests privileged enough to be able to go to four meals at Next rather that try to find four separate reservations? I guess the season tickets make it even easier to fill up the restaurant for the year and reduce the reservations hassle factor for the restaurant. Looking forward to hearing the details….

James is an alley-mechanic – he and his team of five workers repair cars in an alley behind a church on the South Side of Chicago. James rents the space from the church pastor for $50/day. James has been doing business there for twenty years or so. Then, along comes Carl, another alley mechanic. He sets up a garage close to James. Carl hires some homeless people to hand out flyers offering discounts to motorists arriving at James’ repair shop.

James is ticked, to put it mildly. James thinks he has property rights to car repairs in the area – he pays $50/day for this right. He asks the pastor to adjudicate. The pastor is well-known in the neighborhood and often acts as a mediator in contractual disputes. The pastor finds in favor of James. But Carl is not from the neighborhood and does not acknowledge the pastor’s authority. He continues to compete with James.

James turns to an informal court that has developed in the neighborhood. The court arose to settle disputes between rival gangs but it grew to act as a general arbiter of contractual disagreements in the local underground economy. Again, the court finds in favor of James. Again, Carl ignores the determination of the “court” as it has no authority over him. Finally, the pastor is forced to use old-fashioned contract enforcement – violence. He hires a gang of thugs to beat up Carl and his crew and drive them out. End of story

(Source: Talk by Sudhir Venkatesh at the Harris School, University of Chicago)

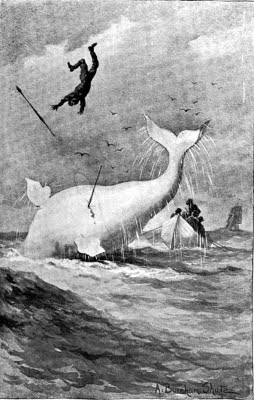

Hamlet: Do you see yonder cloud that’s almost in the shape of a camel?

Polonius: By the mass, and ’tis like a camel, indeed.

Hamlet: Methinks it is like a weasel.

Polonius: It is backed like a weasel.

Hamlet: Or like a whale? Polonius: Very like a whale.-William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 2

For most of your career, you have toiled away getting bonuses, stock options and the like. Your CEO believes in pay for performance and the data says you have performed so you have been paid. You are so successful that promotion beckons – the CEO appoints you to a senior position, advising her on key investments your firm must make to expand. She has her eye on building a new factory in Shanghai and she asks you to look into it. The investment might be good or bad. Your hard work collecting data on potential demand and costs will help to inform the decision. But there is a key difference. In your old job, your hard work led to higher measurable profit and you were paid for performance. In your new job, information acquisition might as well lead to a signal that the investment is bad as to signal that it is good. In other words, a bad signal does not signal that you did not collect information while bad performance is your old job was a signal that you were not working hard. How can the CEO reward pay for performance in your new job?

Since there is no objective yardstick, the CEO must rely on a subjective performance measure. Your pay will depend on a comparison of your report with the CEO’s own signal. The problem arises if you get a noisy signal of the CEO signal. Then you have a noisy assessment of what she believes and hence a noisy signal of how your report will be judged and hence renumerated. In equilibrium, you will condition your report not only on your signal but also on your signal of the CEO’s signal. You are a “yes man”. The yes man phenomenon arises not from a desire to conform but from a desire to be paid! Prendergast uses this idea as a building block to study many other topics including incentives in teams. The greater the level of joint decision-making, the problematic is the yes man effect. He points out that if the CEO asks you to back up your opinion with arguments and facts, this mitigates the yes man effect. Plus he has the great quote above at the start of his paper.

The members of a firm must work together on a big joint project. There are many ways the project could be implemented. One obvious procedure is dictatorial: the CEO simply choses her favorite option and demands that everyone follow her orders. This is sometimes called directive or narcissistic leadership. Another procedure is more participative: The CEO asks everyone their opinion and a decision is made. Everyone might vote so the decision is made democratically or at the very least the CEO makes everyone’s opinions into account before making the decision herself.

In an emergency situation where decisions need to be made quickly, dictatorial leadership makes sense. If you are in the middle of capturing Bin Laden, there is no time to mess around with participative leadership. One person gives orders and everyone follows.

But in many other situations, it is wise to ask everyone’s opinions before embarking on a joint project. The obvious rationale is that information is dispersed and communication might help to aggregate information. The less obvious reason (to economists!): If people do not feel they “buy into” the decision, they are not going to work hard. There may be no information to aggregate but the mere fact that everyone votes means that even the minority who voted against the decision feel committed to it.

A firm is thinking about making a huge new investment. After consultation and deliberation, the CEO and the employees unanimously decide the project should go ahead and initial investment begins. As time passes more and more members of the organization realize that the investment is not a good idea after all. It is better to cut and run. Some costs are sunk and the NPV looking forward is negative.

The CEO is in charge of the continuation decision but his incentives are not aligned with the organization’s. Privately, he was actually reluctant to pursue the project. Publicly, he boasted about the investment, how great it was all going to be, how great the firm would be when the investment paid off. The CEO cannot go back on his word. The market will judge him purely on whether the investment is made and whether it pays off. He cannot cancel the project and instead he forces it through. If it pays off, his career takes off; if it fails, his career is a shambles but is is also in a tailspin if he cancels the project. The employees watch anxiously. They will give him a year and if nothing works, they will look for opportunities elsewhere.

Hat Tip: Frank’s comment in post below