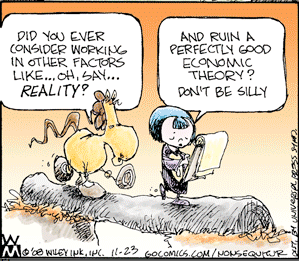

What is good economic theory? What is “applied theory” vs. “theory”? Different people and departments have different answers to these questions. Attempts to define these terms and then categorize papers using the definitions is fraught with problems. Good economic theory is like pornography: You recognize it when you see it. I am led to this conclusion by reading a paper “Model Building vs Theorizing: The Paucity of Theory in the Journal of Economic Theory” in Econ Journal Watch. The authors define good theory using three questions: Theory of what?, Why should we care?, What merit in your explanation?. They then categorize papers in JET in 2004 using the three questions. They ask the questions in order: a paper must pass the previous question for the next even to be applied. By “what”, the authors mean “some fact in the real world”, by “care” they mean to ask “is it important to explain the fact” and by “merit” they mean “have you given the best explanation or an original one”.

What is good economic theory? What is “applied theory” vs. “theory”? Different people and departments have different answers to these questions. Attempts to define these terms and then categorize papers using the definitions is fraught with problems. Good economic theory is like pornography: You recognize it when you see it. I am led to this conclusion by reading a paper “Model Building vs Theorizing: The Paucity of Theory in the Journal of Economic Theory” in Econ Journal Watch. The authors define good theory using three questions: Theory of what?, Why should we care?, What merit in your explanation?. They then categorize papers in JET in 2004 using the three questions. They ask the questions in order: a paper must pass the previous question for the next even to be applied. By “what”, the authors mean “some fact in the real world”, by “care” they mean to ask “is it important to explain the fact” and by “merit” they mean “have you given the best explanation or an original one”.

I claim that a good economic theory does not have to satisfy the first question. Indeed the main paper the authors hold out as an example of good economic theory, Akerlof’s Market for Lemons, I would argue fails the first question. Akerlof was not trying to explain some fact in the real world. In fact the used car market does not break down completely and may work quite well (see a paper by Hendel and Lizzeri in AER 1999) but this does not undercut Akerlof’s theory as it was never meant to describe the used car market. Akerlof utilized the used car market to illustrate the idea of adverse selection. I claim he definitely passes the “why should we care” question, not because to he explains some fact but because he identifies a fundamental issue that impacts all trade under common values and asymmetric information. Whether it is a big effect or a small effect is an empirical question; adverse selection may face some countervailing effects that minimize its impact. But Akerlof certainly explained the logic of adverse selection incredibly clearly. To identify countervailing effects, you first have to understand adverse selection. Akerlof’s model is totally original and hence he also passes the third test.

Nash equilibrium also fails the first question – it explains no fact. It passes the other two (broadly defined) as without this notion of equilibrium or its variants it is impossible to study strategic interaction formally. Much of the research published in JET might fall into this category – fact-free but with the potential to be important in social science research. But identifying this papers with some defined criteria is impossible.

Finally, unlike the physical sciences, economics has a normative theoretical component which is prescriptive not predictive. This also fails the first question but is important nevertheless.

So, certainly both non-theorists and some theorists have little patience for research that displays mathematical ingenuity but has no value as social science. But defining this work exactly is impossible. This sort of work is like pornography quite simple to recognize when one sees it. Unlike pornography, it draws no large audience and is quite easy to ignore.

10 comments

Comments feed for this article

January 26, 2011 at 7:30 pm

zermelo

Did Ken Arrow provide any examples of actual dictators, while proving his possibility theorem? What merit then his explanation of whatever it was he “explained”?

And anyway, why must each individual paper/model build a “theory”, if individual cells do not each build an organism.

January 27, 2011 at 12:57 am

Why EJW?

Although EJW sometimes publishes good surveys, its editors seem to be heterodox economists. I thought that they picked JET simply because they just want to criticize “mainstream” theorists for its apparent detachment from reality; otherwise, they should have started their bibliographic study from AER, AEJ micro, or RAND.

So why did you even care that article?

January 27, 2011 at 1:01 pm

Sandeep Baliga

Just came across it by accident (perhaps via MR?) and thought it was funny.

January 27, 2011 at 10:55 pm

Simon Board

It seems they only like Macro papers – this suggests their selection reveals more about their tastes than the substance of the articles.

January 29, 2011 at 7:38 pm

Sandeep Baliga

If the first part of your definition says theory must be empirically motivated, it is going to select towards macro, finance etc. I think the macro bias comes from that not the authors themselves.

Sandeep

June 4, 2015 at 5:01 am

lhxtns@gmail.com

asics outlet singapore

July 18, 2023 at 8:37 am

The road to nowhere… or explaining human cooperation – Petter Holme

[…] This blog post isn’t really about this the incredibility of economic models, and definitely not only about it, and sure, economics seems to get more realistic by the day… Anyway, nice cartoon by Wiley Miller from this blog post. […]

July 2, 2024 at 9:20 am

Theory and reality in economics | LARS P. SYLL

[…] Jeffrey Ely […]

July 4, 2024 at 6:06 am

Weekend read: Theory and reality in economics | Real-World Economics Review Blog

[…] Jeffrey Ely […]

July 4, 2024 at 6:57 am

Weekend read: Theory and reality in economics – ECONOMICS

[…] Jeffrey Ely […]